Getty images

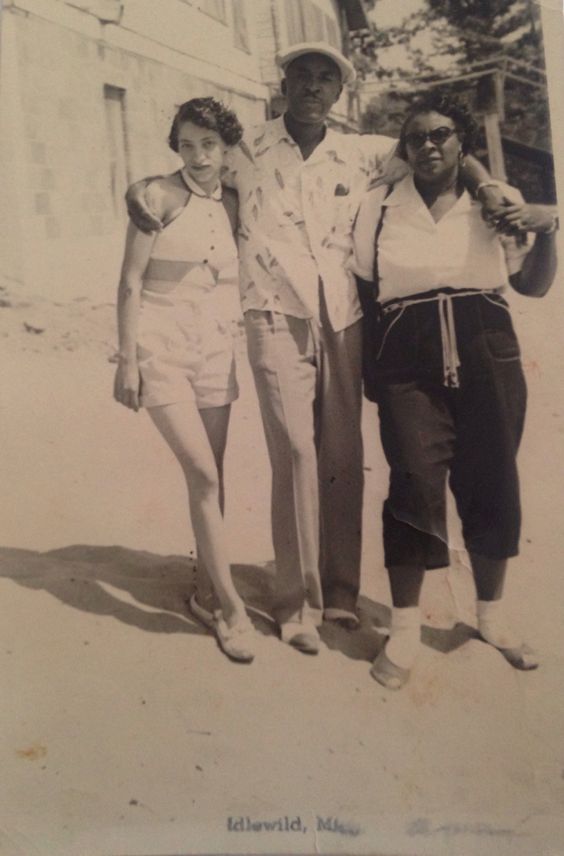

Today, the glory days of Idlewild feel a bit like a fever dream. Just ask any of the African American vacationers who made the pilgrimage to the Michigan resort from the 1910s-60s. “It was something that you’d never believe…stranger than fiction,” reflects one woman in Coy Davis Jr.’s documentary, Whatever Happened to Idlewild? In the midst of Jim Crow segregation, Idlewild became so much more than just a summer retreat for the affluent black community. It was a Garden of Eden.

Getty Images

Getty images

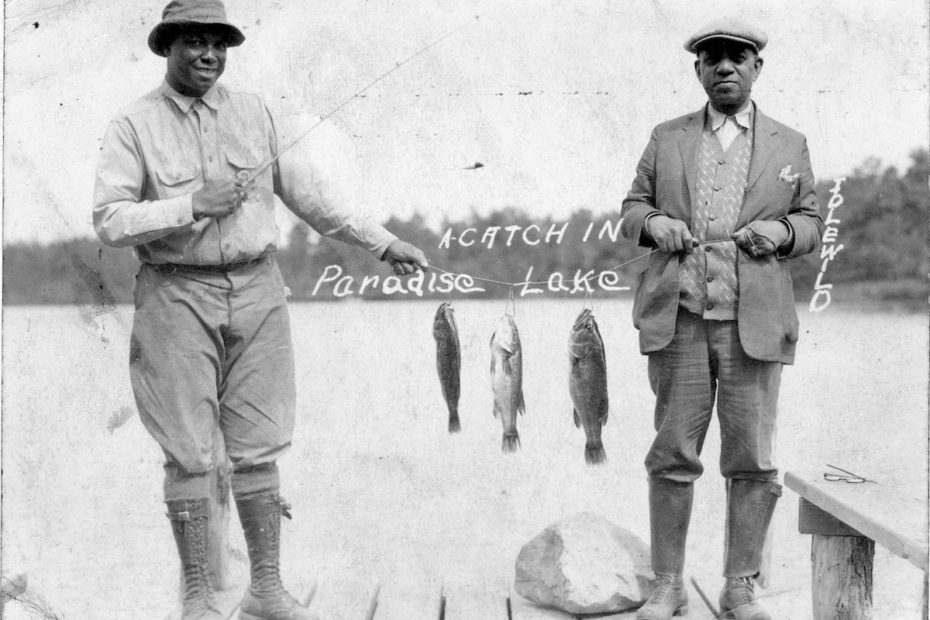

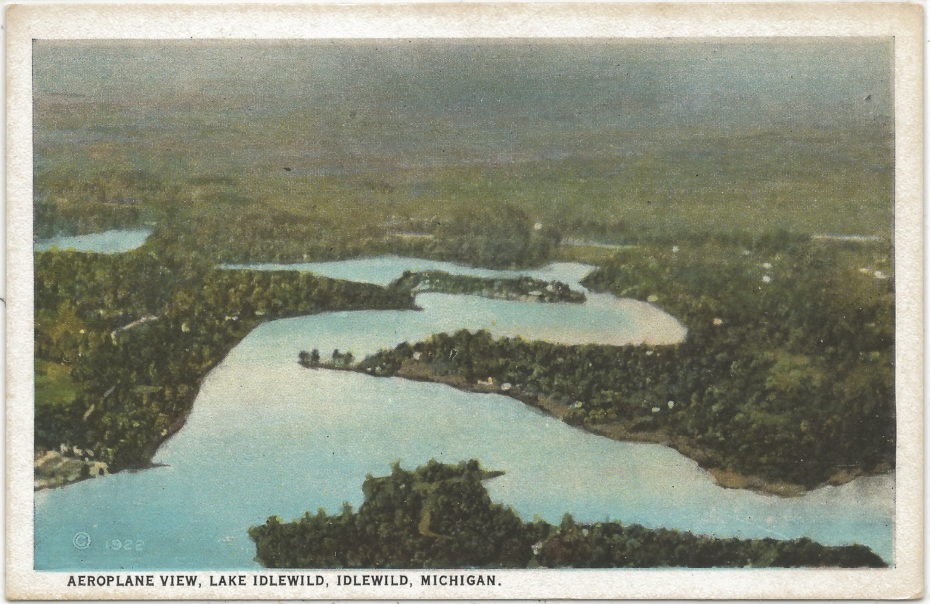

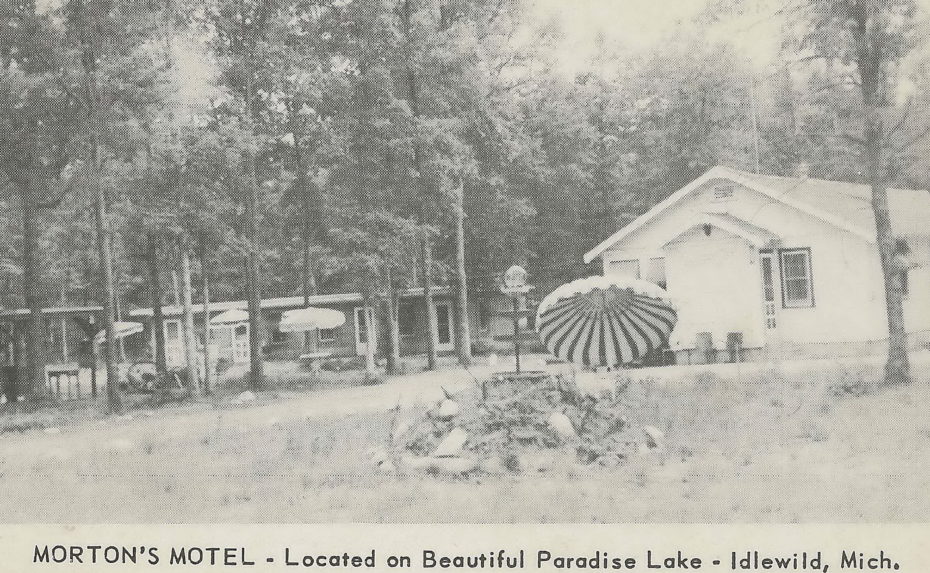

Idlewild still sprawls over 2,700 acres of Southeast Lake County, just a stone’s throw from Chicago. In 1912, a few ambitious white businessmen realised the potential of creating a luxurious retreat for African Americans — an often “untapped market”— amidst the forests and lakefront properties the area promised…

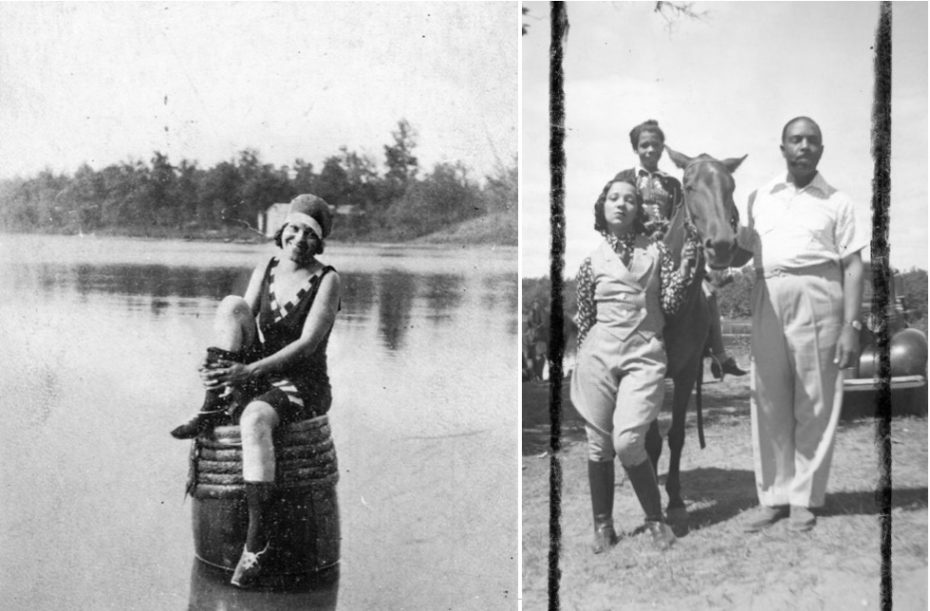

There’s nothing palatable about the systematic injustice that led to the need for a “black friendly” resort, but in the face of it all, Idlewild became a haven: a place where African Americans not only felt they were safe, but could flourish.

“[It] was the mecca of black success,” says a historian in the documentary, “anyone who was anybody in the black community had either been to Idlewild, “or was coming”. One of the first black men to bring the area to life was Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, who performed the very first open-heart surgery in U.S. history:

There were also more modest cabin accommodation, and the wealthier affluent families — who would buy 80 acres, move in, and bring modern amenities with them — had a positive domino effect on everyone there.

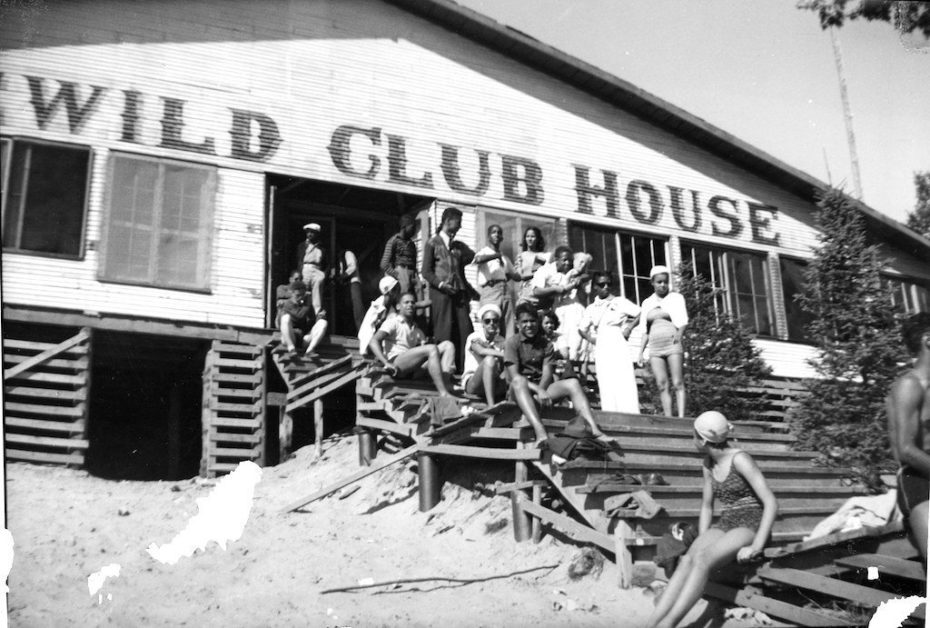

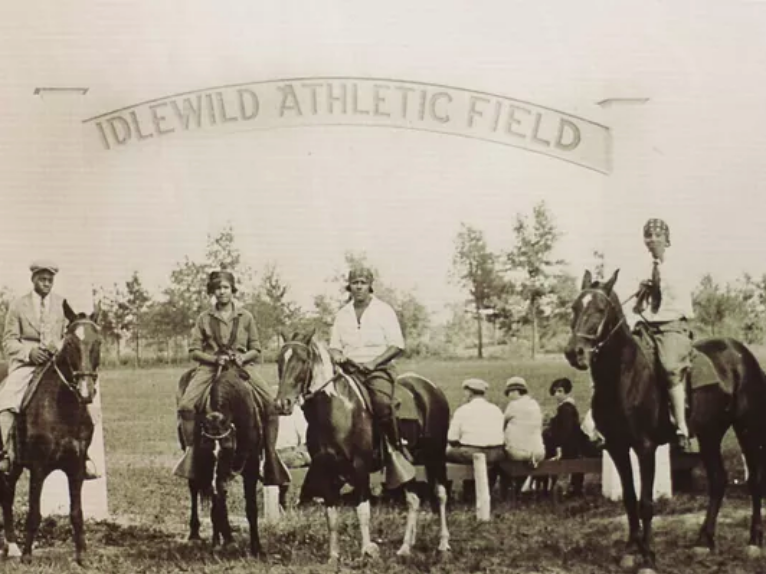

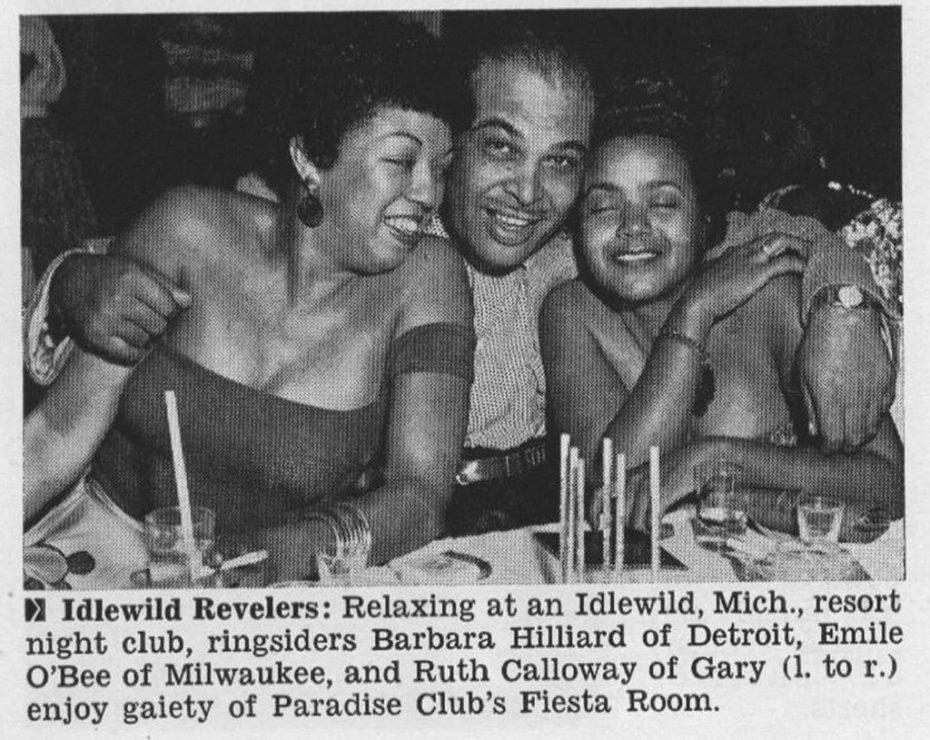

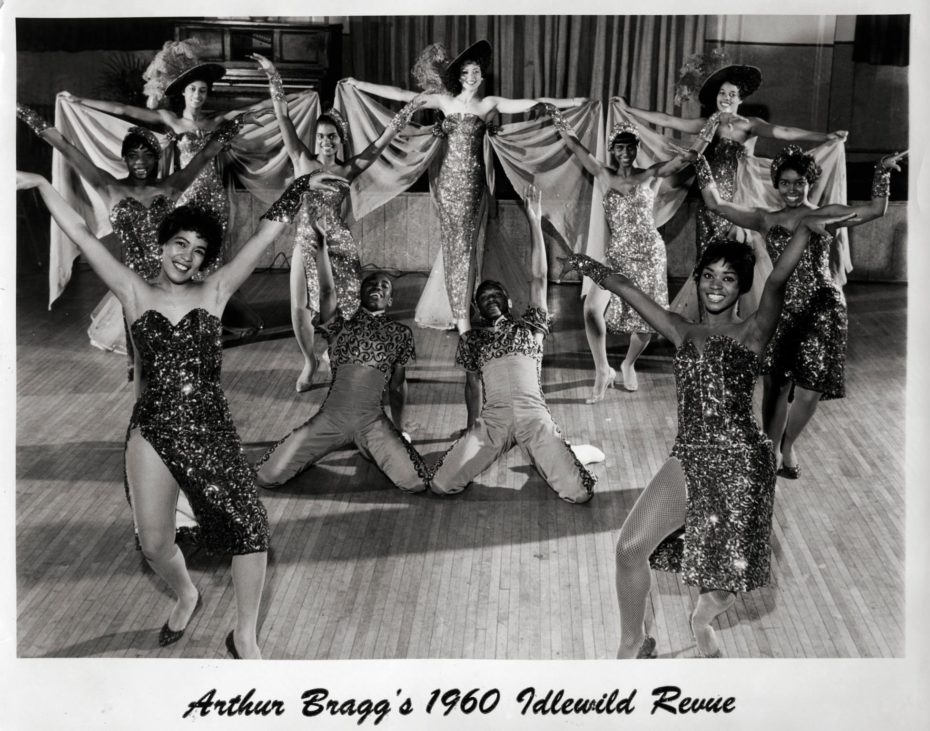

You’d play polo in the afternoon, catch an afternoon “Miss Idlewild” beauty pageant, and get a nightcap at the dreamy Flamingo Bar or Paradise Club with members of the “black intelligentsia”.

Amongst some of the heavy hitting vacationers? Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Cab Calloway, Lena Horne, NAACP co-founder W.E.B. Du Bois — the list goes on and on…

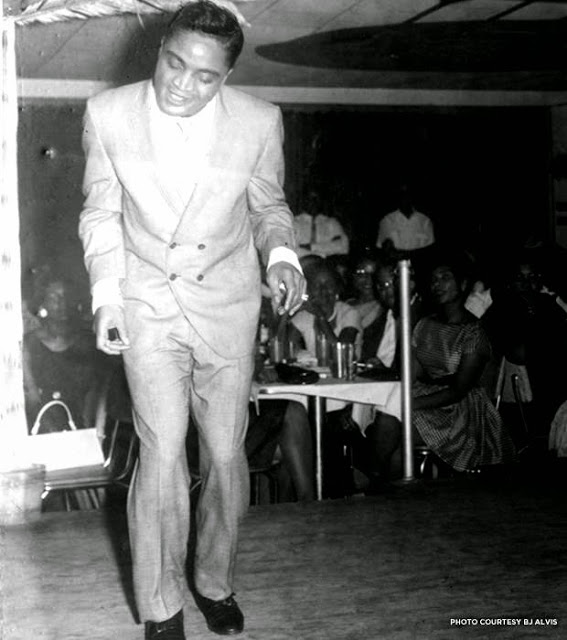

The Paradise Club

Jackie Wilson at the Paradise Club

“Idlewild was where black folk with disposable income went to party,” Ben Wilson, emeritus professor of Africana studies told Michigan Live. “It was a destination for rich people who didn’t want to sweat to death in the summer.”

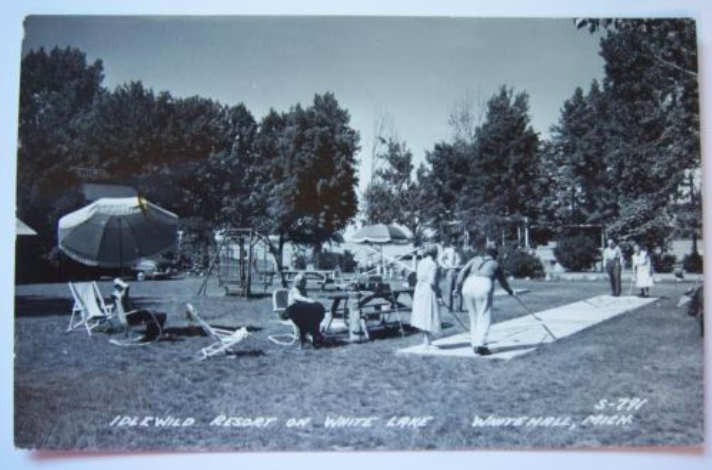

By the 1950s, Idlewild was at its peak. “We ate at the Shrimp Hut and watched matinees at the Paradise Lounge,” Ann Hawkins, told Chicago Tribune in 2012, “Years later, a skating rink was built and quite popular among the young people. We played tennis. We did it all.”

That all changed with the abolishment of segregation. “I understand we were so eager to become part of the nation that we had been disassociated from that we jumped at the opportunity to go places that we had been restricted from,” said Patricia Arnell-Turner, who moved to Idlewild long after its heyday, to Detroit Free Press, “There were positive things… but there were negative things that were not thought out. We should never have abandoned what we already had.”

After falling into near ghost town-territory in the ’70s and ’80s, Idlewild began tearing down some of its abandoned structures. The lakeside retreat is still kicking today (and even planned an “Idlewild revival” event last month). In time, hopefully it’ll be kicking up its heels like it used to…