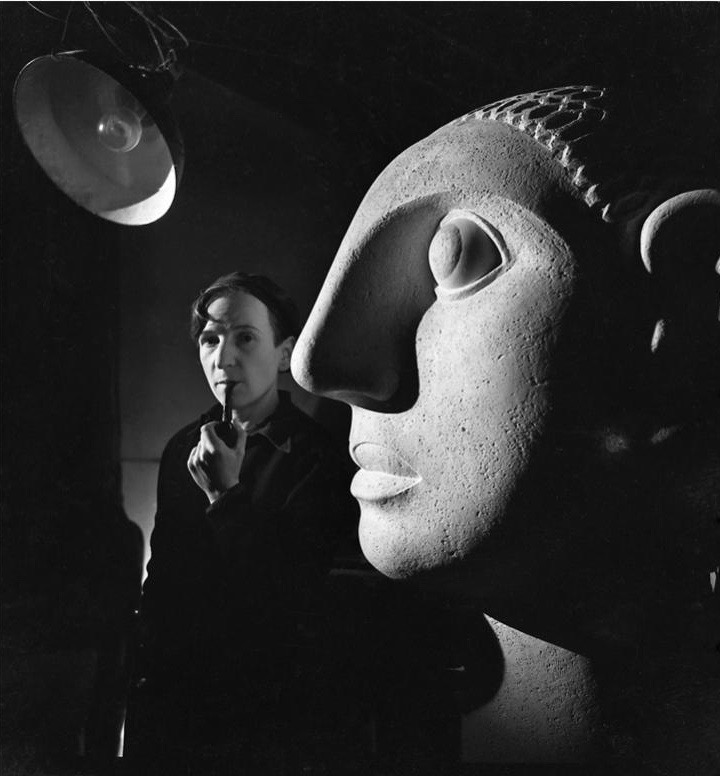

From the darkness, it reared its head. An aquiline nose, about a foot in length, jutted forth from the androgynous sculpture like only a Picasso can – yet, a Picasso it was not. The startling work was made by Anton Prinner, yet another of the art world’s more overlooked sensations. To the public, he was a mystery. To Picasso, he was “Monsieur Madame,” because Prinner — née Anna Prinner – only adopted a male identity when he moved from his native Budapest to Paris in the 1920s. It was there, in the heat of the Left Bank in the roaring ’20s, that he used art to bring his journey with gender identity into a more public sphere. Then, just as swiftly as he burst on the scene, he disappeared. So why did he pump the breaks on his creative momentum? What became of Anton Prinner, the non-binary Picasso of our dreams?

Note: As Prinner asked the public to refer to him with male pronouns after moving to Paris, we’ve decided to use them as well.

Prinner was born on New Year’s Eve, 1902, and studied painting at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts. In 1926, two of her paintings found their way, by accident, into a “Grand Contemporary Masters” exhibit in Budapest. Luckily, the critics and the public alike loved what they saw. Thus, on the coattails of success, Prinner left for the city where everything exciting was happening: Paris.

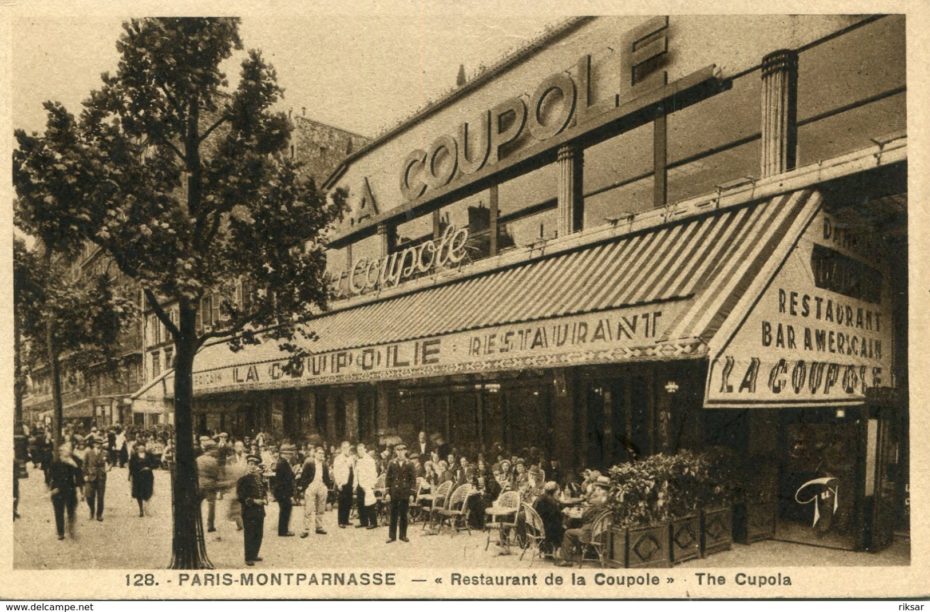

Back then, if you had talent, gall, and knew how to get to Montparnasse, it was easy to rub shoulders with the rising stars of the avant garde – but it was harder to make a lasting impression. Pinner, who stood at 4ft, 9inch (1,50 mètre), knew she needed to stand out. So she cut her hair, picked up a pipe, and began to introduce herself as “Anton”. The freshly baptised Anton became a regular at La Coupole, holing up at the same table for a weekly burger, and falling-in with all the other Montparnos (the nickname for regulars of Montparnasse) with something new to say.

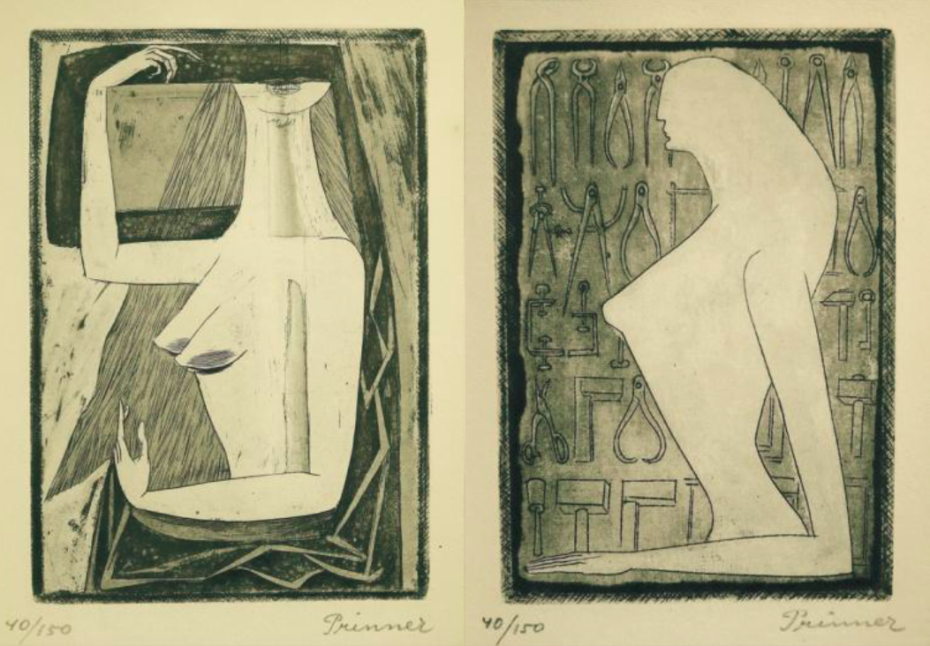

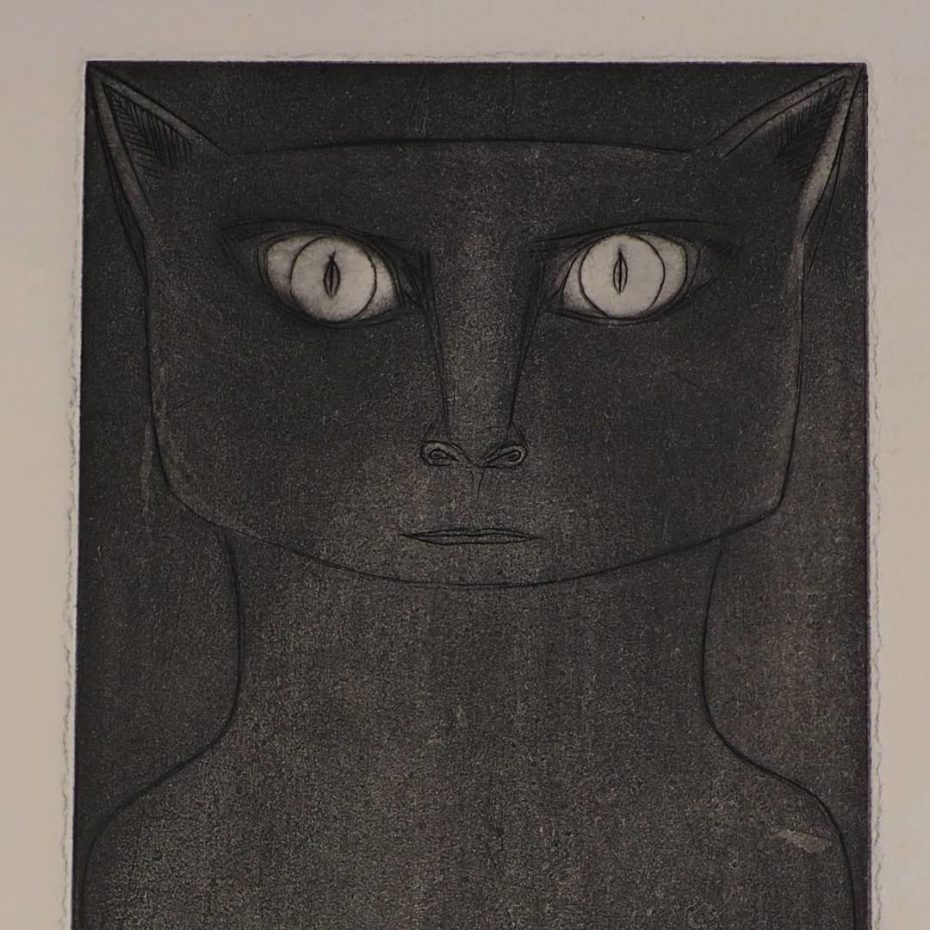

For Anton, that something was Constructivism, which filled his brain into the 1930s in the form of various etchings, engravings and sculptures, and paved the way for his most iconic figurative works in the 1940s. A growing interest in Egyptology was the perfect pairing for his geometric style, and he created near hieroglyphic works for Gravures de l’Apocalypse (Engravings of the Apocalypse) and The Egyptian Book of the Dead. In 1932, he even invented “papyrogravure”, a technique that uses cardboard instead of copper plates in the engraving process.

A fascination with the occult sciences was trendy amongst many Parisians, arty or otherwise, in the 1920s. But for Prinner, the rather androgynous world of Ancient Egypt held a special allure. In Reversal of Gender in Ancient Egyptian Mythology: Discovering the Secrets of Androgyny, Ashley N. Dawson explains that “the transfiguration of sexuality acts as a vital source of spiritual balance in all realms of Egyptian existence, ushering

the soul into a state of androgyny in order to completely embody the power of both phallic creation and the maternal womb”. Man, and woman, as one. It was perfect for Pinner, who adopted a signature “cosmic” signature, of two intersecting triangles.

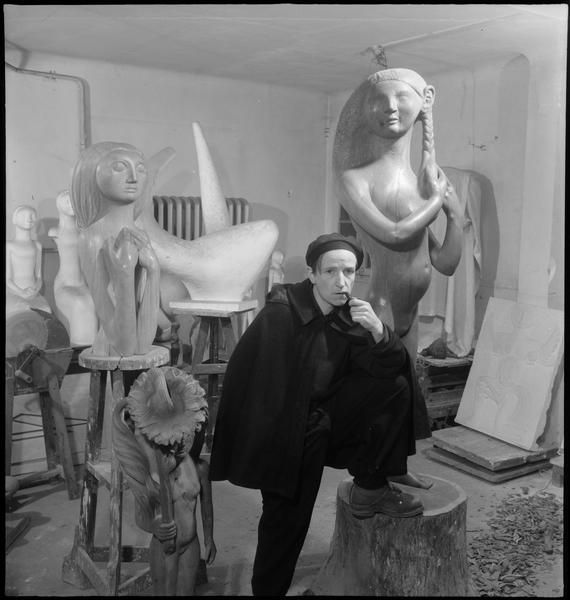

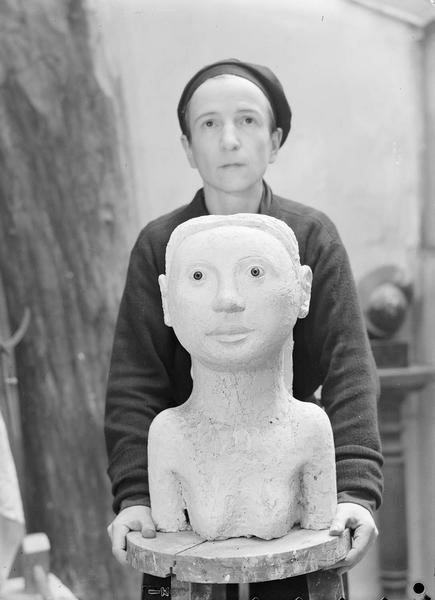

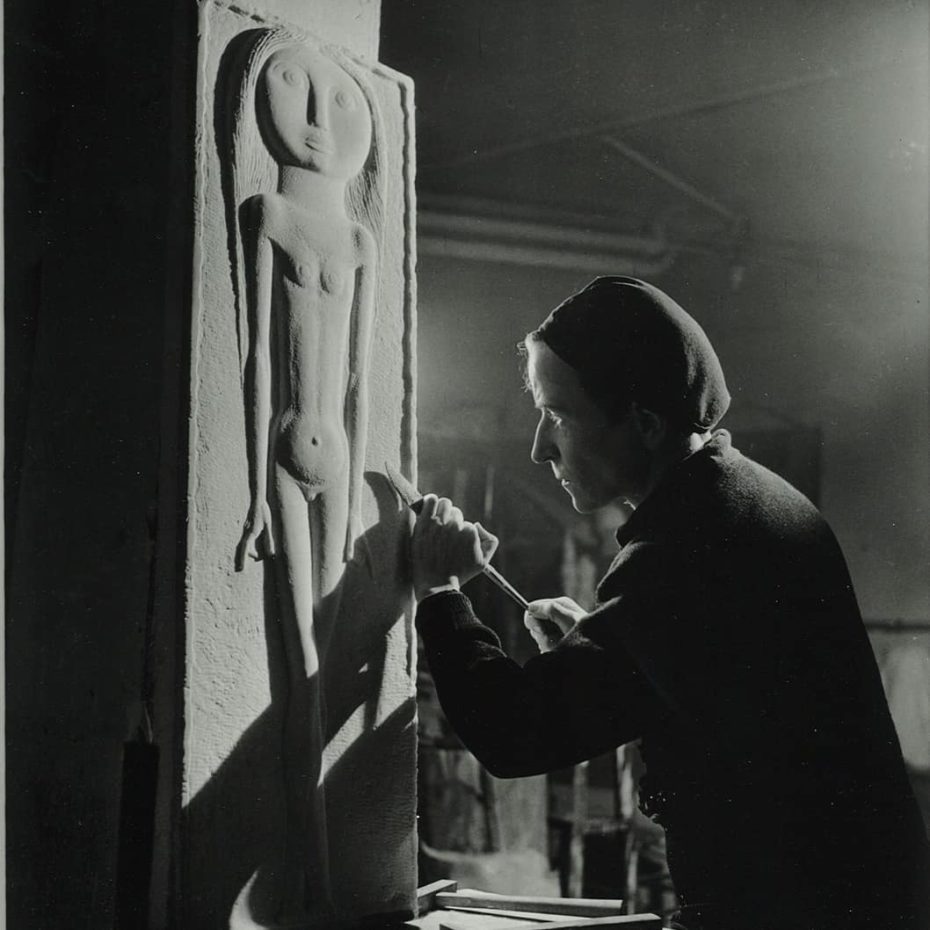

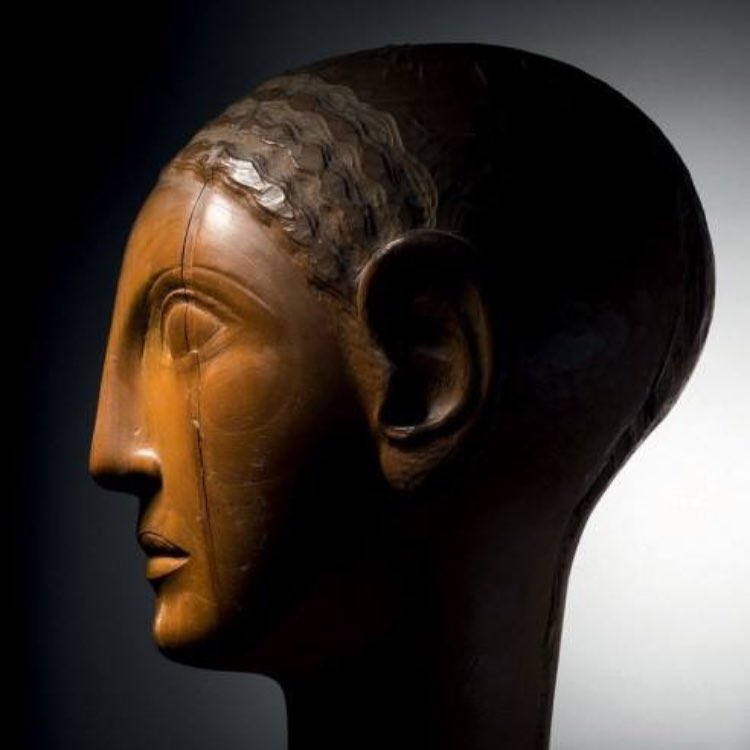

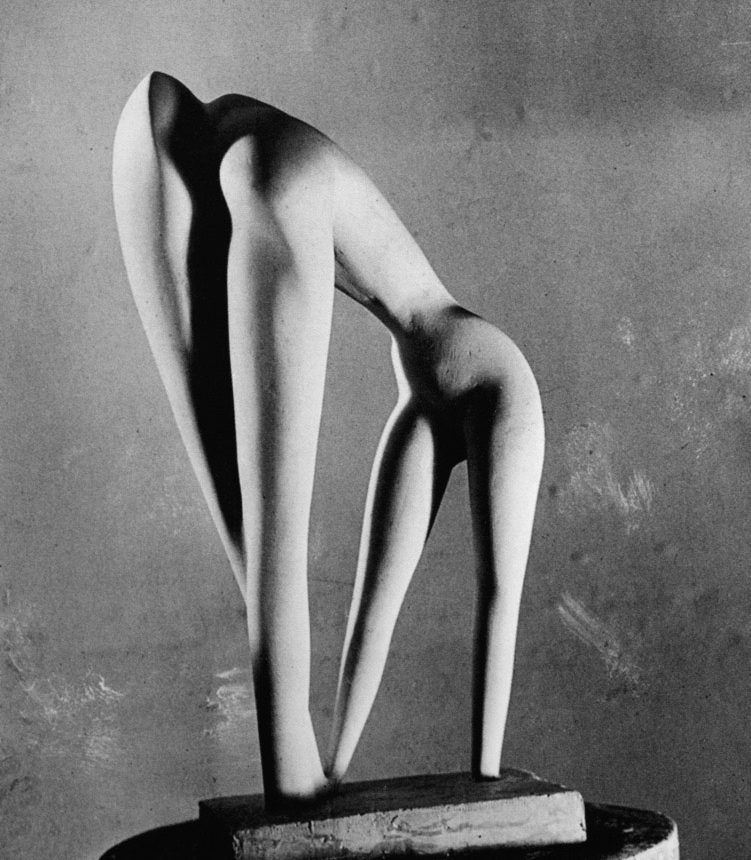

His works almost always featured powerful, androgynous or hybrid beings, like Femme grenouille accroupie (Squatting Woman Frog) which looked like a golden idol fresh from Tut’s tomb, or the sculpture, La Femme aux grandes oreilles (The Large-Eared Woman), whose elegant swan neck was topped with a bold face and heavy forehead. He even made a delightful chess set.

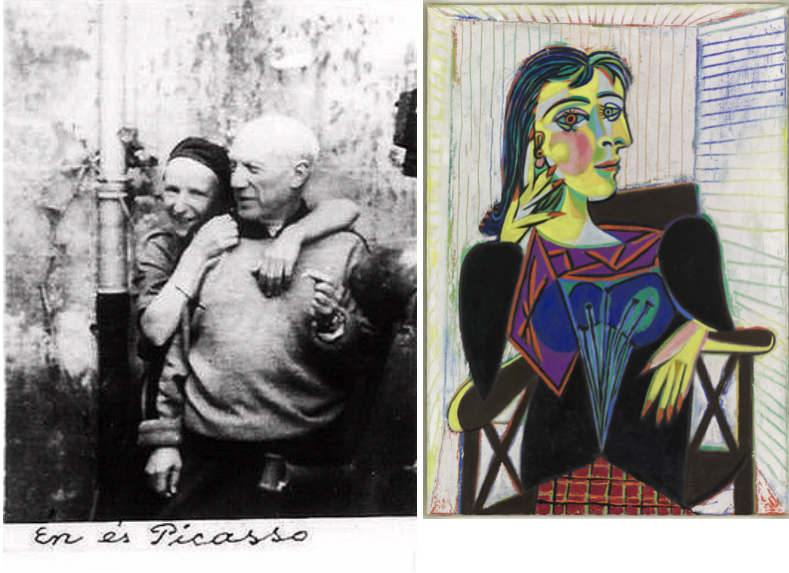

By the 1940s, Pinner was particularly chummy with Picasso, who called him “The Little Woodpecker” for his ability to create great things despite his small stature. Like Picasso, Pinner also sought to explore human relationships – with the other, with the self – through subjective and abstract forms of portraiture. Yet, for Picasso, this exploration with women often tapped into his infamous, toxic machismo. “For me there are only two kinds of women,” he once told a pupil, “goddesses and doormats”. The abstract lines that quite literally drew out his love interests, from renowned figures like Dora Maar, to lesser-known muses like Sylvette David, were lustful, loathing, and tenacious. They were always, in this respect, bound to the geometry of his desire. Prinner was different.

“People say artists have to try and understand themselves,” Prinner later wrote in his journal, “I’m doing the best I can not to understand myself. Which is a lot harder, a lot more meaningful. I’m a non-existentialist. I’m not myself: I’m everybody”. It’s a perfectly coy explanation of Prinner’s identity as understood through his work, weaving in and out an admirable universalism in a way that avoids a more difficult subject: himself. Prinner was very private, and we don’t know much about his potential romantic relationships. We don’t even know if he identified as transgender man, or if, as some historians say, he became “Anton” only to make a place for himself in the boys’ club of Constructivism, Figurativism, Surrealism – pretty much every arty “ism” in the Paris art world.

Prinner’s subjects were stately. Sometimes, borderline stoic, but always in-control, and it was with that empowering geometry that he then coupled all the vulnerability, fear, and sensuousness of the “other” in a way that felt relatable. The sheer weight of the hybrid, amorphous sculptures anchors them to the earth as if saying, “I, too, deserve to be here, just as I am”. The universalist angle, while not untrue, probably speaks just as much to the malleability of his own gender identity.

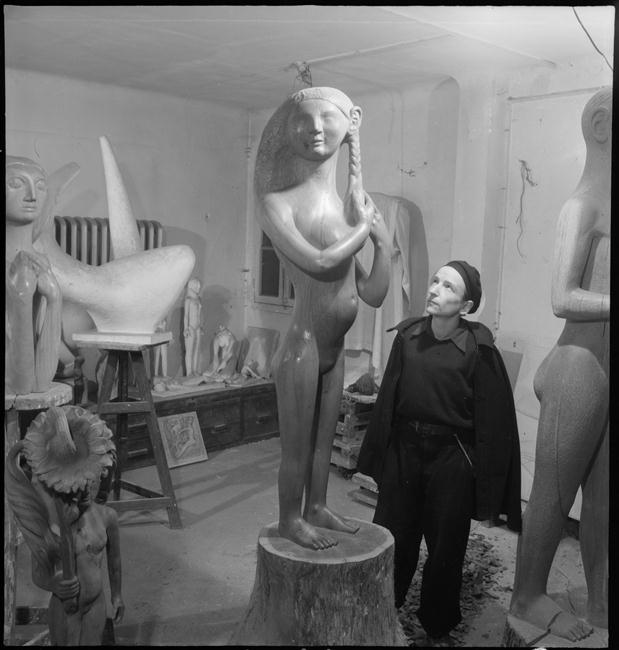

In the 1950s, despite the urgings of Picasso, André Breton, and Jacques Prévert to stay in Paris, Prinner headed south to Vallauris on the Côte d’Azur. The statues get bigger, massive even – as if he were gearing himself up to make idols of truly Sphynx-like proportions for his generation. But just as Pinner’s creativity exploded, so too did his anxiety. Convinced that those at the famous Tapis Vert ceramic atelier were stealing from him, he abandoned sculpture altogether for painting. “I want to do things that no one will like,” he said about the shift, “that way, no one will steal from me”.

When he passed away in Paris in 1983, he was penniless, and more private than ever. As time time went by, his story faded from public memory like so many other creatives from that era. Now, more than ever, we think it’s high time for museums and art historians to revisit Anton’s life – to curate his pieces with the rigour they deserve, and celebrate them as catalysts for an open, empowering conversation on gender identity. Until then, we’ll be lassoing in his works from online auctions (check out his pieces from a past auction here).