Originally, this was supposed to be a pretty straight-forward piece on an American ex-pat artist whose enchanting paintings of 1930s Paris I’d recently had the fortune of stumbling across via the internet. She was a young woman who had moved to France before the war, where her painting career began to flourish. I was going to share her Parisian street scenes with you, touch upon what I could find about the positive experience she would’ve had as a young Black woman in pre-war Europe, and probably wrap up with a nod to her more notable abstract work later produced while living in Haiti. But then, before I got the chance to write it up, the largest civil rights movement in world history unfolded in the space of a week, and suddenly, nothing about her story felt “straight-forward” anymore. Ultimately, this one artist, Loïs Mailou Jones, would lead me to discover many more African-American artists like herself that came to Paris, whose legacies have been neglected, whose work is missing from art history books and the walls of our museums. She would also introduce me to her social cohort of Black creatives known as “The Little Paris Group”. And unlike literature’s famed Lost Generation of Paris, this was the first I’d ever heard of it. Go figure.

It wasn’t just the jazz. Paris was an artistic mecca for African-American artists both before World War II and for a good 20 years that followed.

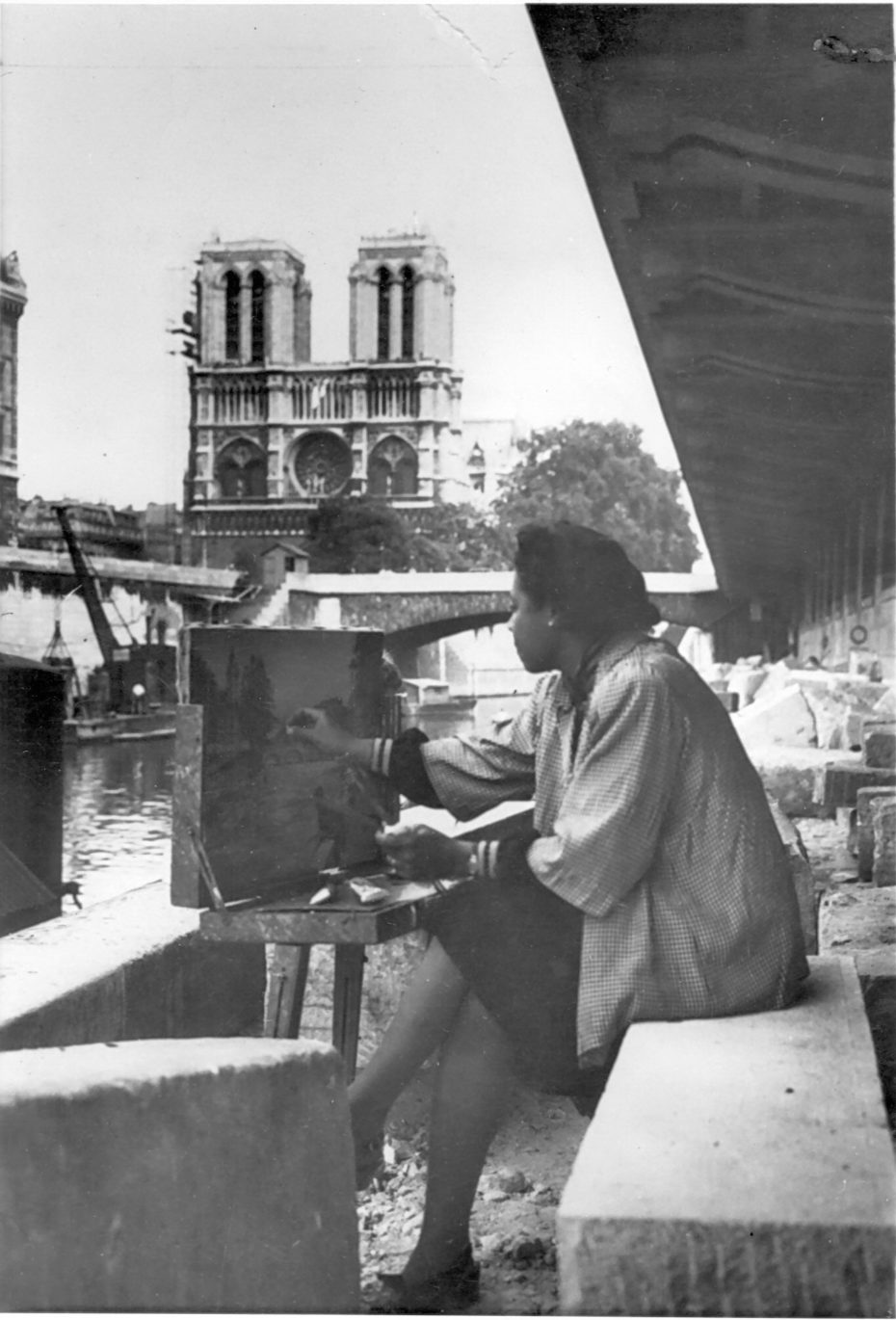

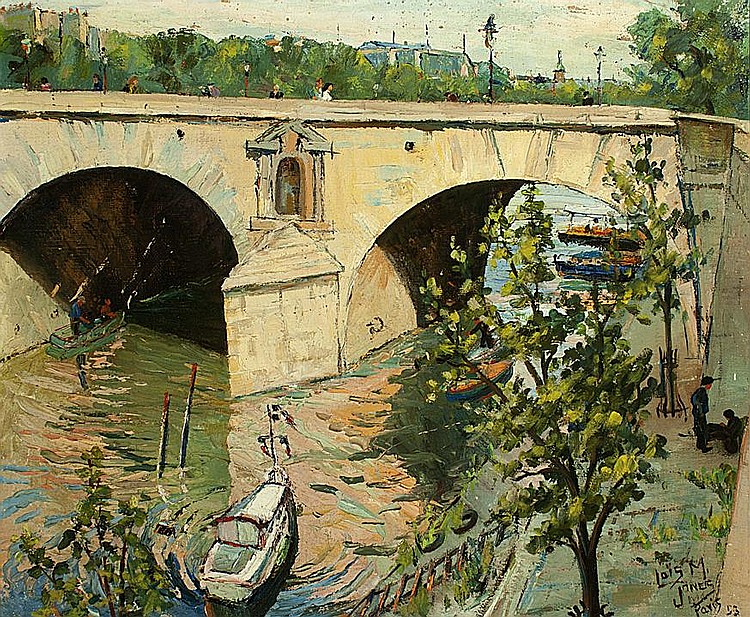

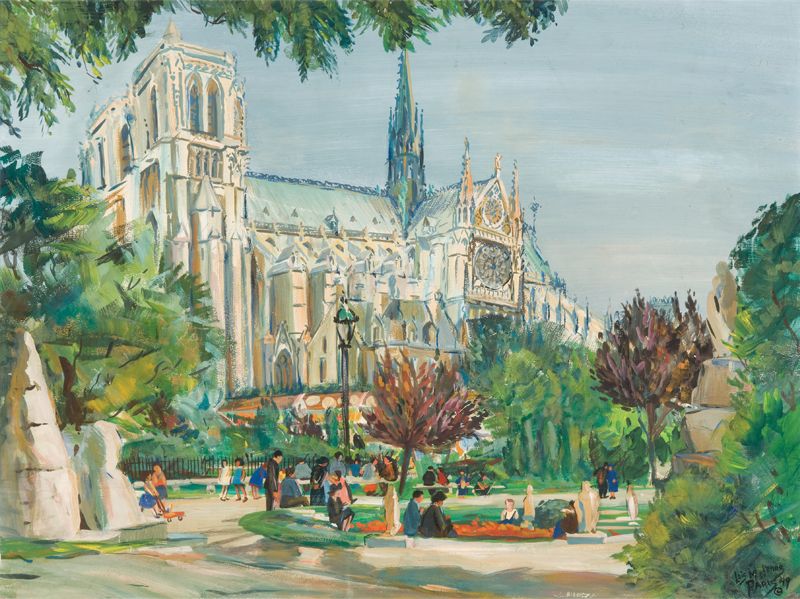

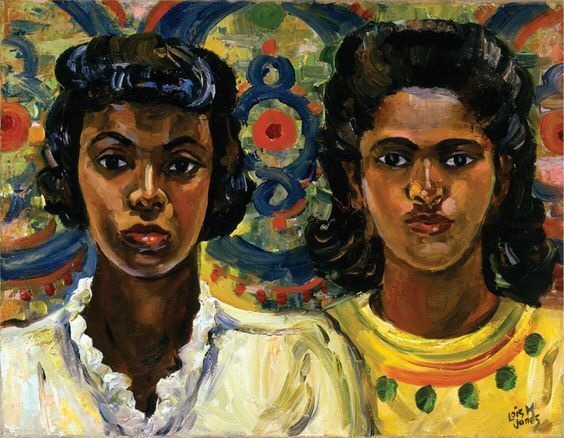

Loïs Mailou Jones arrived in Paris in 1937 on a fellowship with Howard University. She began painting al fresco, producing dozens of oils and watercolours in the French tradition, enjoying the freedom to nurture her talent without the relentless racial prejudice she was faced with everyday back home in America. In Paris, she could live, eat and most importantly, paint wherever she chose.

“The French were so inspiring,” she recalled of her early years in Paris. “The people would stand and watch me and say ‘mademoiselle, you are so very talented. You are so wonderful.’ In other words, the color of my skin didn’t matter in Paris and that was one of the main reasons why I think I was encouraged and began to really think I was talented.”

Loïs had developed herself as an artist from a young age, taking night classes at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts thanks to the encouragement of her parents and later, attending the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. She received a BA in art education from Howard University and began a teaching career there in the 1920s, while spending summers in New York, becoming involved in the onset of the Harlem Renaissance, which would greatly influence her work. The great American poet and leader of the movement, Langston Hughes, would later provide the text for one of her most prominent Paris works, Parisian Beggar Woman.

In 1952, the book Loïs Mailou Jones: Peintures 1937–1951 was published, reproducing more than one hundred of her art pieces completed in France. She has been described as the only African-American female painter of the 1930’s and 1940’s to achieve fame abroad. She returned every year for more than two decades after her first residency.

As war broke out in Europe, Loïs was left with no choice but to return Washington D.C, accompanied by Céline Tabary, a French artist she’d met and studied with in Paris. They became lifelong friends, and Loïs helped her find a teaching job in the arts department at Howard University. As a white émigré from France, where black American culture was being given so much attention, Tabary fought to champion African-American art in 1940s Washington, D.C. It’s important to acknowledge however, that while France has historically given a lot of attention and respect to the black American culture, ironically, the same respect hasn’t been afforded to the Black people born and raised in France.

Yearning for the same recognition she had received in Paris, Jones began entering her work for various jury prizes and competitions held by prestigious galleries where African-American artists were prohibited from entering. Determined to see her art exhibited in America, it was up to Céline to submit the paintings for her. When Jones’s work won an award from a prestigious gallery, Tabary had to secretly mail her the prize. Fifty years after being forced to hide her identity, the Corcoran Gallery of Art publicly apologised to Jones at the opening of their exhibition The World of Lois Mailou Jones.

During the years of the Paris Occupation, when Jones and Tabary couldn’t return to France, they formed a Parisian-style salon and invited local artists to hone their skills and exchange critiques twice weekly at Jones’s studio. They nostalgically called it “The Little Paris Group”. The dynamic collective included D.C. artist Alma Thomas, Delilah Pierce, Richard Dempsey, Ruth Brown, Don Roberts and others. The idea was to keep its members inspired during an era when there were few venues where African Americans could show their work.

For American artists of colour, Paris represented a place where everything was open to them. Unlike America, a stimulating art scene awaited them in the French capital. Some artists were able to travel on educational grants like Loïs Mailou Jones, or with funding from private patrons. And then there were the American G.I.’s, who, after victoriously liberating France, decided to stay on and see how far a year’s worth of unemployment compensation from the G.I Bill could take them.

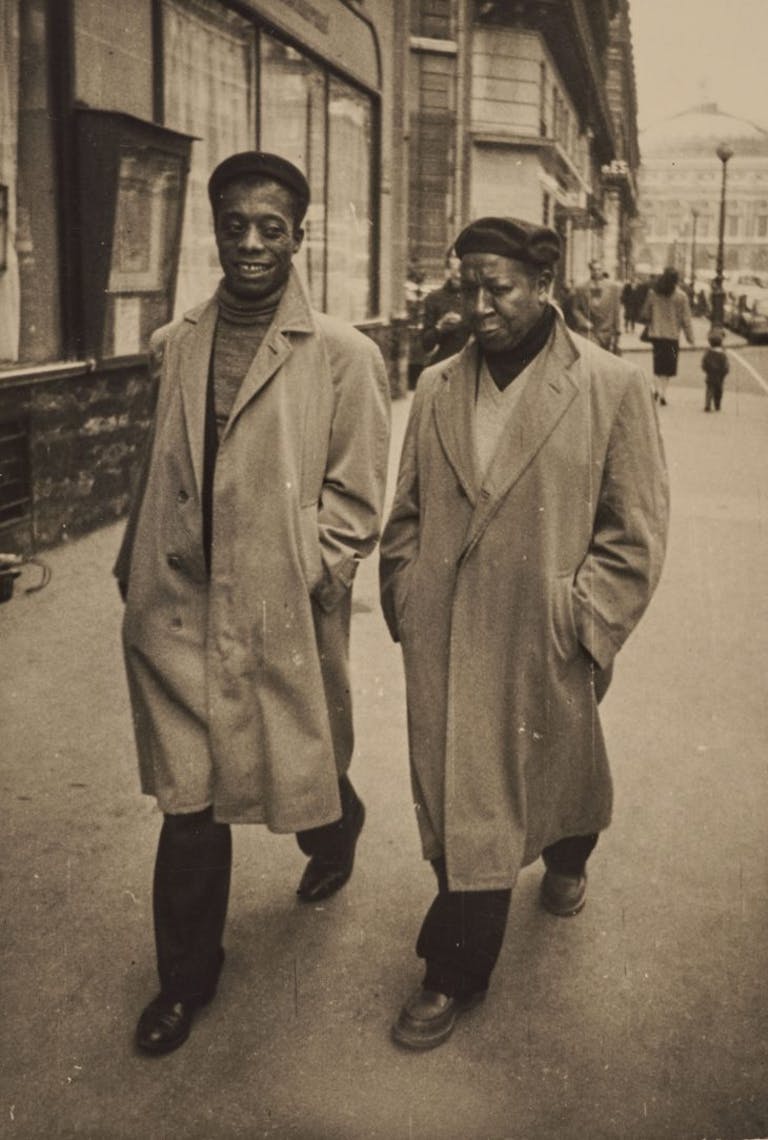

Herbert Gentry, who served in the 90th Coast Guard Artillery for three years, fell in love with Paris and ended up running a Left Bank jazz club in the 1950s called Chez Honey, which doubled as an exhibition space by day for his own expressionist art as well as works by others. Patrons of his club-galerie included Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Juliette Gréco, Eartha Kitt, Orson Welles and Marcel Marceau. Similar to Hemingway, he lived the café life in Montparnasse, meeting fellow American artists at Le Dôme café, Le Select and La Coupole, rubbing shoulders with the likes of Alberto Giacometti, Georges Braque and Jean Cocteau. At Café de Flore, he got to know the great writer and African American activist James Baldwin. On the boat back to Paris after a brief return to New York (where he would later settle to become a permanent resident of the Hotel Chelsea) Gentry met Beauford Delaney, a modernist painter and notable alumni of the Harlem Renaissance movement.

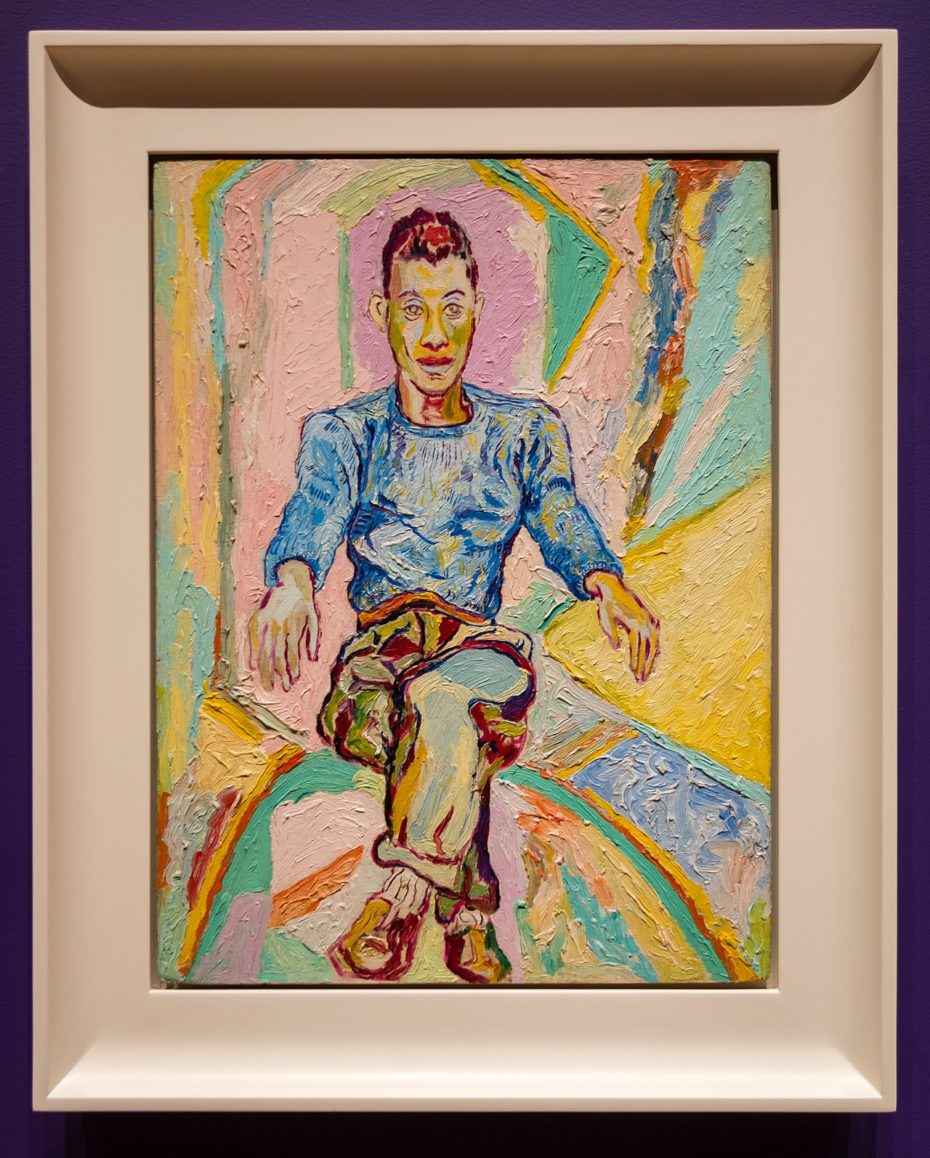

Delaney painted the 1930s urban landscape of New York in vibrant colour and captured the Black camaraderie in Harlem, but remained isolated as a homosexual and fearful of rejection from his own community.

The pressures of being “black and gay in a racist and homophobic society” sent him to Paris in 1952, where he changed his artistic style, studying color and light through abstract expressionism.

Adrienne Childs at the University of Maryland writes that “Delaney’s relationship with abstraction predated the notorious Abstract Expressionist movement, positioning him as a forerunner of one of the most important ideological and stylistic developments in twentieth-century American art.”

He worked so much in Paris that when he ran out of canvas, he was known to paint on anything he could find, including his own raincoat to create “Untitled, 1954” (an oil painting on a raincoat fragment).

The 1960s saw Delaney’s mental health deteriorate and his heavy drinking made it worse. In 1973 a friend wrote to James Baldwin, “Our blessed Beauford is rapidly losing mental control,” and despite their efforts to care for him, in 1975, he was committed to St Anne’s Hospital for the Insane where he died four years later.

He was “the first living proof, for me, that a black man could be an artist. In a warmer time, a less blasphemous place, he would have been recognised as my Master and I as his Pupil.

James Baldwin

Delaney’s portrait of his close friend James Baldwin hangs in the US National Portrait Gallery, but for decades after his death, his legacy was largely forgotten.

“Whatever Happened to Beauford Delaney?”, wrote an editor for Art in America in 1994, asking, “Why did Beauford Delaney so completely disappear from American art history?”

While the past few years have been promising for the African American art market, figures show that less than 10% of exhibitions in America’s top museums feature work by African-American artists.

Arts writer for Cultbytes, Caira Moreira-Brown, did a search across Ph.D. programs at various universities across the US, and was only able to count 13 African-American art historians. “With the steady rise of the African-American art market,” she notes, “both expanding and strengthening scholarship in the field is urgent […] Now is the time to unearth important artistries that have been overlooked. The increase in buying and selling also acts as a driver for institutions to collect and show African-American art.”

In 2017, Jean-Michel Basquait surpassed Andy Warhol’s highest artwork sale with the sale of his Untitled skull painting for $110.5 million at auction. But try asking your neighbour if they can name just three other African American artists besides Basquait, or even one.

Art Net reports that the total African-American art market has generated $2.2 billion at auction in the last 10 years, but one single artist, Basquiat, accounts for $1.7 billion of the art sold. “The historic lack of mainstream attention creates real potential for market growth”.

Cultbytes writer Moreira-Brown reminds us that “museums need assistance in tackling the issue of representation”, citing non-profit organizations and smaller institutions trying to counterbalance the exclusion of African American artists, such as Souls Grown Deep, Swann Auction Galleries, The Studio Museum in Harlem and the Museum of African Diaspora in San Francisco.

Loïs Mailou Jones, whose work is now in museums all over the world including the Met and the National Portrait Gallery, felt that her greatest contribution to the art world was “proof of the talent of black artists,” but her greatest desire was to be known as an “artist”—without labels like black artist, or woman artist.

She died in 1998 before the world was ready for that shift from “African-American artist” to “American artist’ (and you can still find some of her Paris oils on canvas for as low as $2,000). But in the wake of a 21st century civil rights movement – possibly the largest and most significant the world has yet to see – could we be heading for a new African-American renaissance that will finally incorporate this lost generation into the mainline narrative of American art history?

In the meantime, why wait? Keep discovering and help blaze the trail.