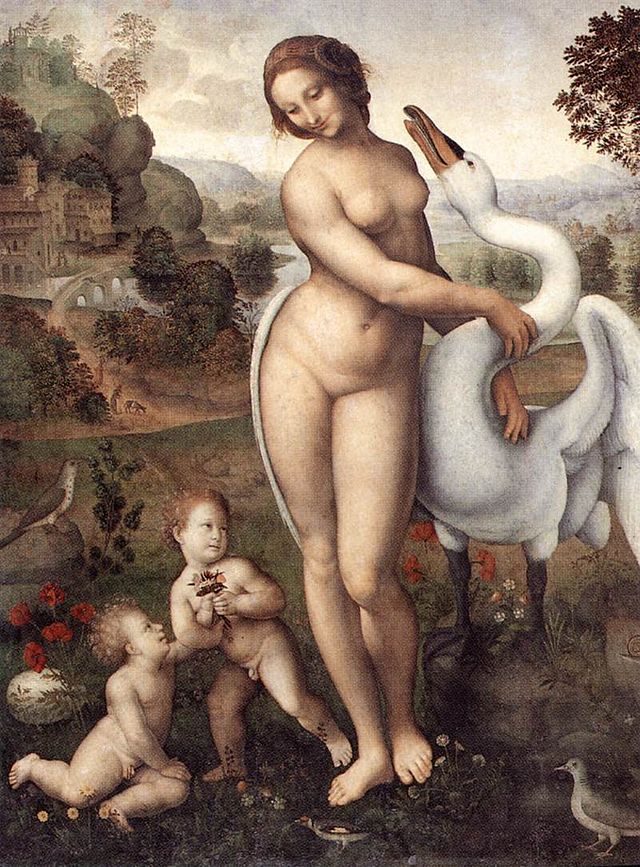

There’s something not quite right about that painting, wouldn’t you say? The many depictions of Leda and the Swan are hanging on the walls of some of the most prestigious museums and galleries across the world, and yet, there’s a conversation we’re not having. The Greek myth in which the Spartan queen Leda is seduced and raped by the Greek god Zeus while he is disguised as a swan has been a frequent subject of artistic and literary interpretation for as long as art history’s records go back. It has been a captivating, titillating and irresistible painterly subject for many artists including the great masters Leonardo Da Vinci, Michelangelo and Paul Cézanne over centuries. In almost all renditions, the subjects of bestiality and rape are romanticised, glamorised and not portrayed as the sordid acts that they are. Renaissance painters even showed Leda overtly welcoming the swan into her lap, often with a voyeuristic Cupid supposedly consensually looking on. Sexual violence and assault have often been depicted as totally acceptable forms of romantic conquests in folklore, and when the rapist also happened to be a god, the victim was expected to perceive the act as an honour. At best, art is a grey zone: not only is it notoriously difficult to define, as a construct it’s so much more than just the ability to create imagery from paint, canvas, stone and bronze. At its core, art is an immensely powerful social tool, not only for artists, but also for their patrons. It more often than not, has an agenda; it broadcasts messages, makes social commentary and draws attention to causes. Art is evidently also first and foremost about an artist’s choices of subject and interpretation. And this is why Leda and The Swan, The Greek myth in which the Spartan queen Leda is seduced and raped by the Greek god Zeus is so contentious.

The Renaissance; the great movement of late 15th century Europe that promoted the ‘rebirth’ of the arts from Roman antiquity. The ancient Greeks and Romans had left us fragments of those perfectly proportioned temples and near-perfect human sculptures. The Catholic Church based in Rome, the key force behind this movement, set about using the imagery of Ancient Greece and Rome to promote and maintain the cultural supremacy of the Roman Catholic Church. The reuse and appropriation of all things classical – architecture, sculpture and art – would be the essential tools sought to further their cause. This unfettered access to the ancients’ cultural menu opened the Pandora’s box of the exotic and sordid tales of the classical gods and their exploits – good or evil, exemplary or unworthy. Whilst the Renaissance church’s manifesto promoted, on the one hand, nothing but the monotheistic Christian message – there would certainly have been no additional religious ‘gods’ in this message – but they were more than happy to condone and encourage the use of the old legends as subject matter in this classical ‘promotion’. Now under the guise of acceptance by the church of this classicism, the artists and their patrons would have free license to illustrate and create interpretations of all those Olympian orgies and fleshy fantasies.

Representation of naked human bodies had been off the menu for almost 1000 years, since the conversion of the pagan Roman Empire to Christianity in the 4th Century. By the 15th century, the common man or woman of Europe had little or no engagement with ‘realistic’ or provocative art; their art was the biblical fables told by gothic carvings and paintings in their churches.

The Greek and Roman myths however, were not just a collection of adventure stories for filling long dark winter evenings, they were also lessons for life in the guises of fables, allegories and religious reasonings. These characters, such as Zeus, king of the gods, Ceres the goddess of Growth and Pan the god of Fertility, carried cultural messages and warnings, perhaps a little like Grimm’s fairy tales to be published centuries later. Serious life lessons were concealed within oftentimes disturbing romantic imagery.

The family of the Greek Gods (which was also the foundation the later Roman version) originated long before the time of Alexander the Great’s Classical Greece. This was a male-dominated world (perhaps due to the need for survival) caused by male aggression and violence where females, not physically on the frontline like their men, were subordinated. Like the tale of Troy, the wars between rival societies became allegories based on the personal exploits the gods and that of mortal nobility such as Achilles, Paris and Helen. But running counter to these societies’ common goal for survival was internal sexual tensions and rivalries. The tales of the Greek and Roman deities recount endless pursuits of women by gods and men, almost like a curse the men could not escape and the women had no choice but to accept. Who chased who, how they chased and the manner of the catch were all to do with status. Zeus, the king of the Greek gods, could have any partner, he had first choice and his approaches were a game. He would employ, seemingly for his own amusement, many guises – bull, swan and even a shower of gold – in order to ‘seduce’ his victims. He, as the leading male was then elevated to the status of conqueror and hero, while the female he had chosen for his attentions became an outcast, exiled from society and would often be transformed or morph into an animal, like Asteria becoming a lioness to escape Zeus or Daphne escaping Apollo to become a Laurel tree. In some tales there was a semblance of revenge, almost justice: Leda was raped by Zeus, they have a daughter Helen who sparked the conflict with Troy which led to 10 years of grizzly war among men. The female would inevitably produce demi-god offspring, who would go on to repeat the pattern. This concept of Heroic Rape cascaded down the hierarchy of gods, reinforcing the male’s conquering status, domination and control of society.

The rape by Poseidon, God of the Sea and brother of Zeus, transformed Medusa from a fair maiden to an aggrieved, feared and outcast gorgon, (seemingly a lesson in whom you choose to have an affair with). The abduction of the ancient Roman goddess Proserpina by Pluto, or in the Ancient Greek version, Persephone abducted by Hades (another brother of Zeus) was a seasonal allegory. Hades took Persephone into the underworld, but her mother Demeter the goddess of the Earth was so enraged that she forced Zeus to intervene and so, Persephone returns each year as the embodiment of spring and summer.

The tale of Leda and the Swan, however, is the most intriguing of them all. In this tale Zeus decided he should have Leda, the married Queen of the Spartans, and transformed himself into a swan to ‘seduce’ her. Leda in turn produced four offspring, all of which would wreak eternal havoc on the world of men, one of which was Helen of Troy. The lesson here is that nothing good could ever have come from the initial deceit by Zeus.

The Greeks and Romans never used the moment of rape or bestiality in these stories as subjects for large public art works. The tale of the rape of the Sabine women, an attack on early Rome’s neighbour, was widely celebrated, but ‘rape’ in this era also referred to abduction, commonplace for rivalrous land grabbing tribes. Greek and Roman depictions of the act of rape were usually kept to smaller frescos, mosaics and pottery and displayed more privately.

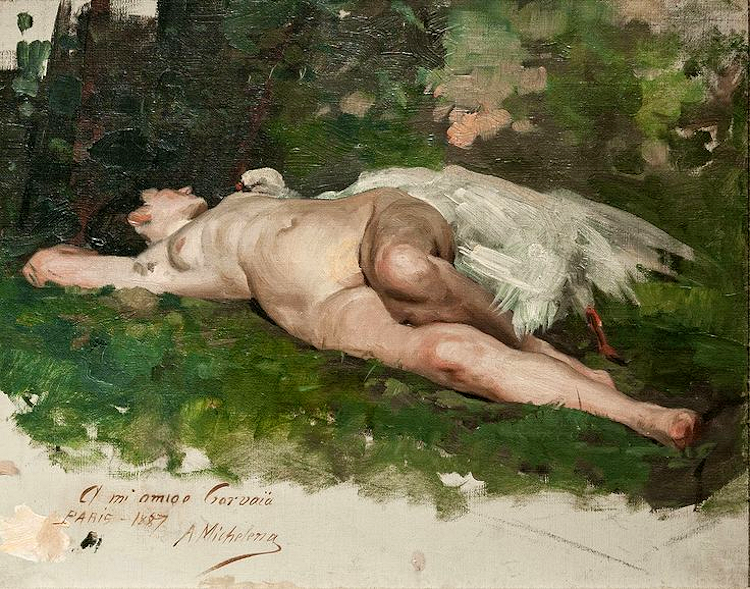

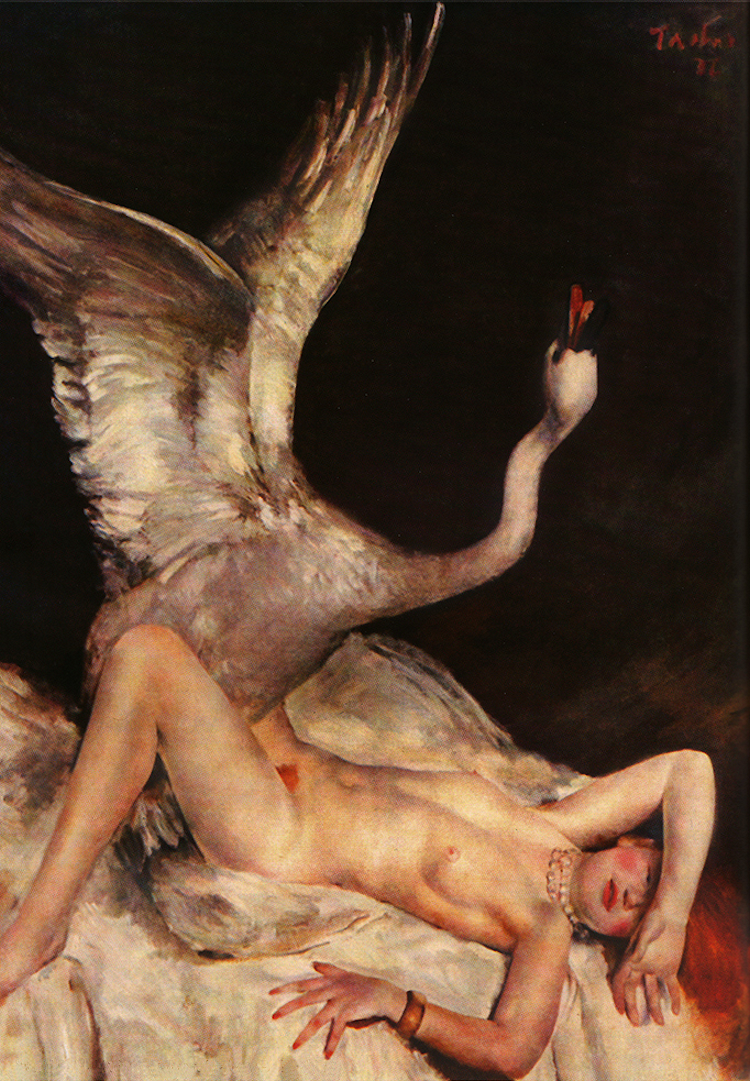

The Renaissance patrons and artists were not afraid to produce large-scale and more explicit renditions of the Greek and Roman tales. From the etchings of the late 15th century onwards, the subject of “Heroic Rape”, a term created for theme which was increasingly sought after, was treated with more and more realism and eroticism. Right up to the present day, tales such as Leda and the Swan have been used to supply an insatiable desire for ever-more sexual explicitness in art. This weaponised sexual art of the Renaissance was too dangerous for general public display. The fleshy gratification parading as ‘culture’ was very much a private voyeur’s game for the pseudo-intellectual but nonetheless continued to broadcast and reinforce the message of conquest by sexual violence.

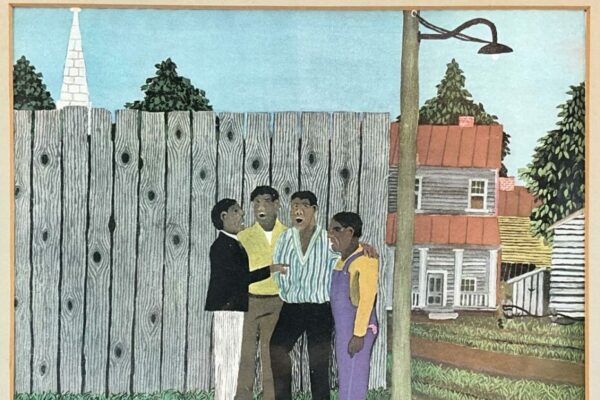

The Renaissance artists picked the most erotic moments from the tales for their works, usually only the moment of assault was graphically illustrated, clearly for voyeuristic titillation. Supporting characters that appeared to normalise the act, such as the presence of cupid in Da Vinci’s Leda and the Swan (1508), served to suggest that Leda was partly responsible. Artistry attempted to downplay or conceal the master-and-slave, attacker-and-object roles, but the compositions were clearly showing the continued domination of the so-called ‘heroic male’ over the objectified females. The Renaissance age had well passed the tribal eras of land grabbing and female abduction, any allegorical message was irrelevant to this modern society and similarly, the original concept of tragedy through deceit is lost. It’s unlikely that the average 16th century layman knew much about Leda and the Swan from the ancient Greek Mythology.

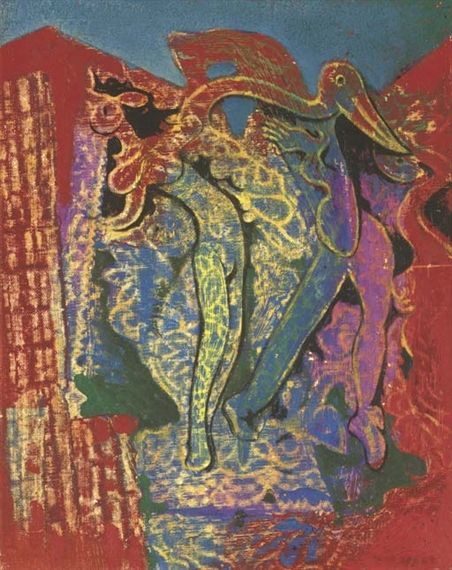

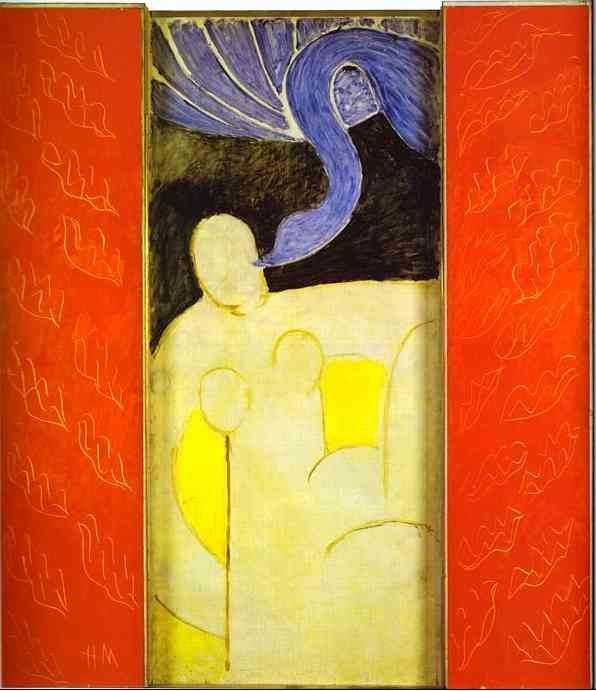

The desire to illustrate and glorify sexual violence under the guise of intellectual classical culture seems to have gained popularity as the centuries passed; indeed it also became more and more explicit. By the 18th century, erotic paintings of Leda and the Swan were produced in abundance and this would continue through the 19th century, including works of Paul Cézanne in 1880 and into the 20th century with the works of René Buthaud in 1930. Max Ernst in 1927 and Henri Matisse in 1946 created rather more ‘tasteful’ abstract renditions of the subject.

Rape Culture is defined as “an environment in which rape is prevalent and in which sexual violence is normalized and excused in the media and popular culture […] perpetuated through the use of misogynistic language, the objectification of women’s bodies, and the glamorization of sexual violence, thereby creating a society that disregards women’s rights and safety.” It’s defining “manhood” as dominant and sexually aggressive and “womanhood” as submissive and sexually passive. It’s gratuitous gendered violence in movies and television. It’s victim blaming and refusing to take rape accusations seriously. There are versions of the story that insinuate Leda welcomed Zeus the swan into her lap. This well-crafted erotic art, albeit beautifully painted, ticks all the boxes for perpetuating rape culture – and yet it hangs in our museums without explanation, without conversation. After all these centuries, perhaps it’s time to stand in front of these masterpieces and start asking the difficult questions.