When we think of Parisian café culture, we might think of the “intello-chic” literary crowd that congregated at the Café de Flore with Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Paul Sartre in the 1950s, or the glamorous flappers that held court on Boulevard Montparnasse during the Années Folles, mesmerising artists like Man Ray and Picasso. It’s an iconic scene, the Parisian café, but who would have thought that we owe it all to an industrious community of coal-shovelling “country bumpkins” that are still running the show behind those zinc countertops…

The story of the Parisian café begins in the middle of the 19th century, amidst France’s industrial revolution and the developing railway. The agricultural crisis was forcing those from rural France out of the fields and into the capital, desperately in search of work. Just before the midpoint of the century, migrants flooded in from the volcanic region of Auvergne in middle France, especially after the Paris to Clermont-Ferrand railway line opened in 1858. Auvergnats represented the largest migrant community in Paris after the rural exodus of the 1880s and 90s. They mostly settled in the 11th and 12th arrondissements, around the Place de la Bastille and Place Voltaire, or near the Gare de Lyon and Austerlitz railway stations where they felt closer to home and would return by train each summer.

To make a living, the countrymen and women took up the hard jobs neglected by city dwellers. Their first and main source of employment was carrying water to fill bathtubs for wealthy Parisians, who without the advent of running water yet, required hot and cold water buckets delivered to their front door. When further industrial development eventually all but eliminated the need for water carriers, ever tenacious, the Auvergnats turned to new and equally undesirable professions such as tinsmith, boilermaker, scrap metal worker, grinder and parquet rubber.

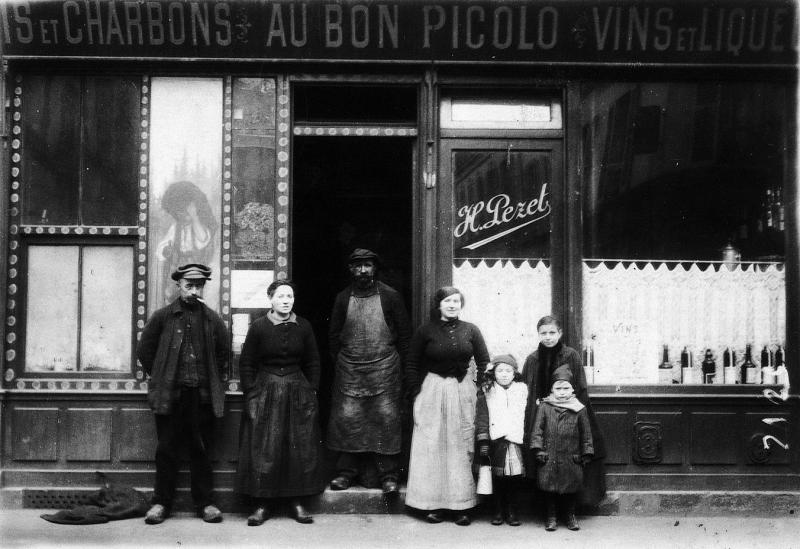

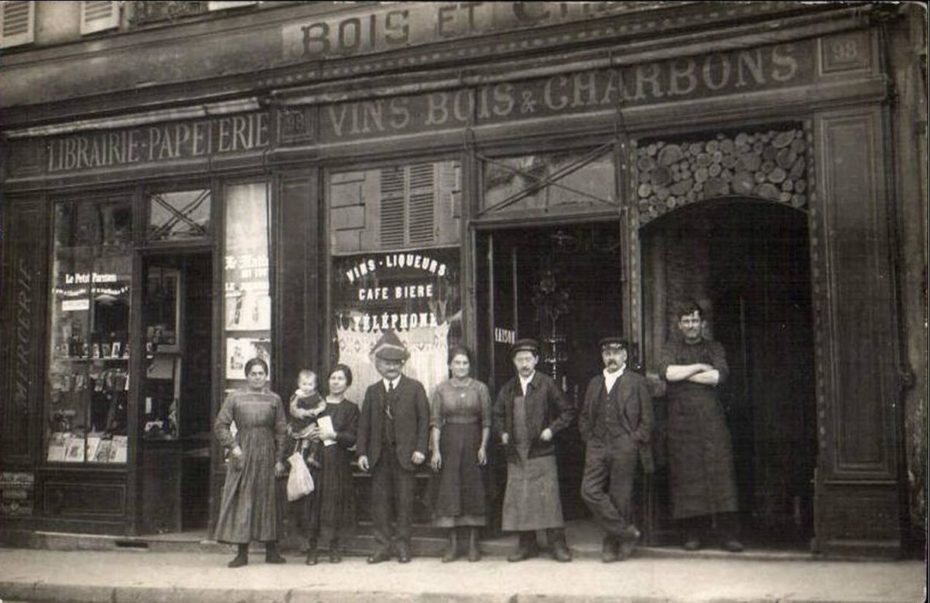

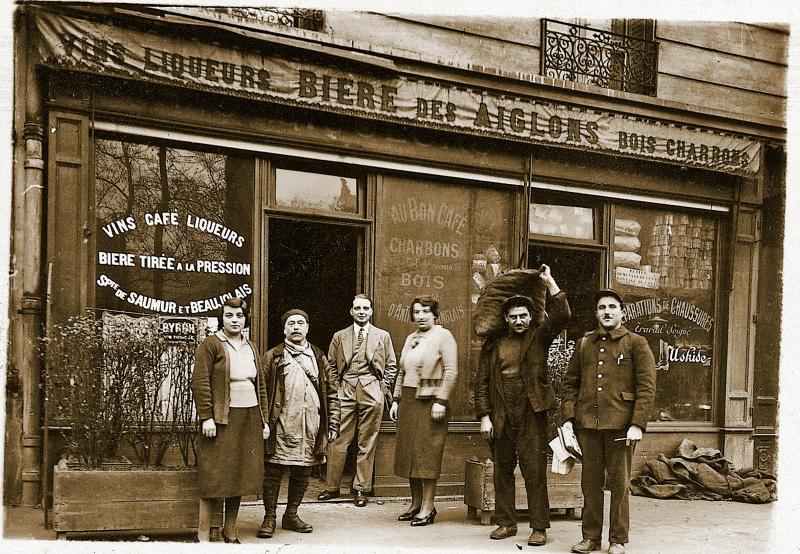

But at the turn of the 19th century, the Auvergnats notably fell into the lucrative business of selling coal, which they imported from Brassac-Les-Mines via rivers and canals. The distribution of coal in winter was also an ideal complementary activity to that of providing cold refreshments in summer. Soon, the need for a shop became apparent to welcome their increasing customer base, as well as a place to store the coal, so the Auvergnats began opening establishments where one could buy or order their charcoal, as well as wine, spirits, and lemonade, eventually diversifying their activity with onsite hospitality.

It’s from these establishments that the Auvergnats earned the nickname “Bougnats.” The term is a portmanteau of the French terms for charcoal burner (charbonnier) and the term for Parisians whose origins are in Auvergne (Auvergnats).

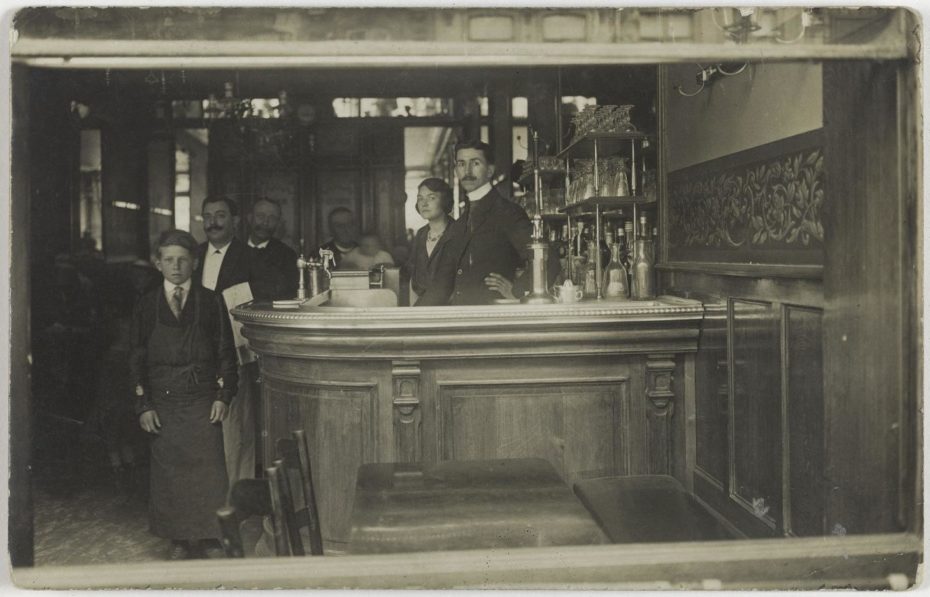

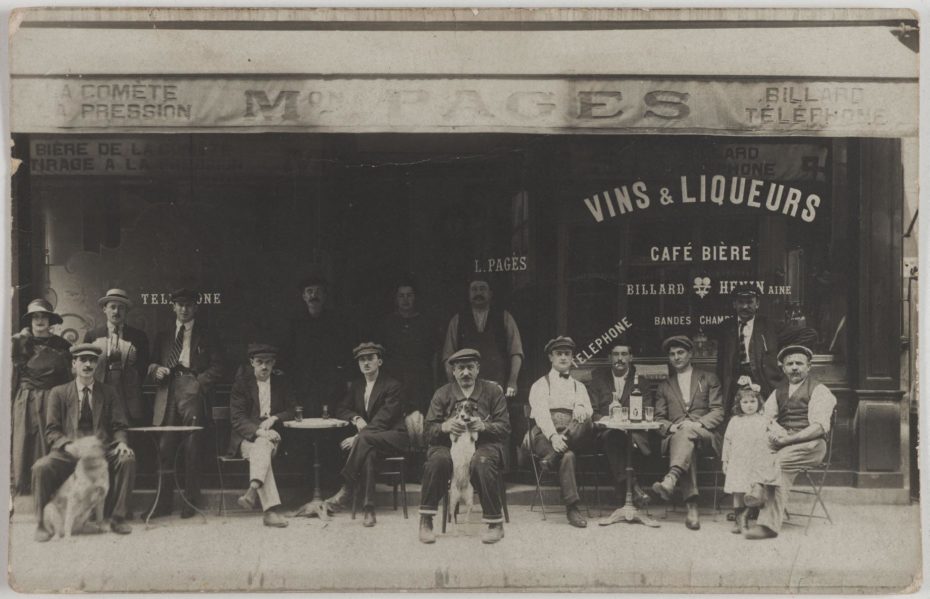

The emerging Parisian cafés themselves were also called “Bougnats” and soon enough, in every working class district, one could see signs painted to read, “Vins et charbons” (“wine and coal”). Women were responsible for serving the coffee and drinks while the men handled the coal . Soon, the enterprising bougnats evolved their shops into veritable restaurants and small hotels.

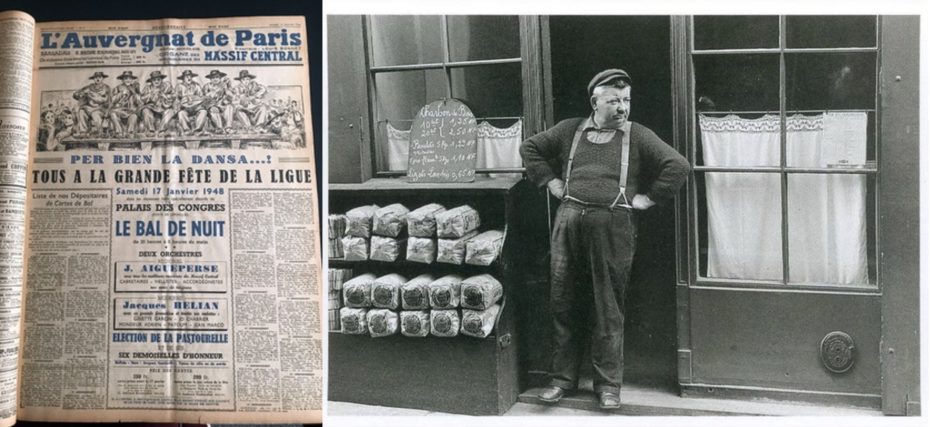

The bougnats even had their own newspaper, L’Auvergnat de Paris, that served as one of their only connections to home, providing regional news from the Massif Centrale. It’s the oldest weekly in France still in operation, and still an essential reference for catering and hospitality professionals.

The first half of the 20th century was the golden age of the bougnats and by the 1930s, some 2,500 family-run cafés welcomed patrons in Paris, but only half of them survived the disruption of World War II.

While younger generations decided to pursue other opportunities outside hospitality, the bougnats are still very much present in Paris today; only its their grandchildren who are running a good chunk of the hospitality industry. Auvergnat families manage 40% of the region’s cafes and 15% of its tobacco bars and still own some of the most prestigious cafés such as Le Café de Flore, Les Deux Magots, Brasserie Lipp and Maxim’s.

Open since 1887, the Café de Flore is not the oldest restaurant in Paris nor even the one with the most renowned cuisine, but it is indeed one of the great Parisian institutions. “On its rattan chairs sit some of the greatest Parisian artists and intellectuals of the 20th century,” including Sartre, de Beauvoir, Boris Vian, Apollinaire, Albert Camus and Pablo Picasso. At a time when many apartments were not yet heated, most of these artists and writers took advantage of the affordable prices of the cafe-restaurant, the warmth of the stove on the first floor, and a small wooden tables to set up their a “surrogate office.” Flore was owned for decades by a Paul Boubal, a notable bougnat born in Sainte-Eulalie-d’Olt, Aveyron.

One block over on Boulevard Saint Germain, Les Deux Magots earned its iconic status under the patronage of the Mathivats, a family from Auvergne, who counted Hemingway as their regular customer, but also Albert Camus, James Joyce, James Baldwin, and Richard Wright. It was even one of Julia Child’s favourites. Across the road, Brasserie Lipp began as a hot water source. In 1935, to attract a more glamorous clientele and Paris’ up & coming talent like its neighbouring competitors, then innkeeper Marcellin Cazes established the Prix Cazes, a literary prize awarded each year to an author who has won no other literary prize. The prize is advertised by the Lipp to this day.

So next time you’re seated on one of those rattan chairs enjoying a bottle of Beaujolais and watching the city go by, raise your glass to les bougnats, who we can thank for nurturing the city’s greatest talent within their cafés that continue to inspire us all.