We love a good story about a missing painting missing. This one starts in Christmas of 2008: a Hungarian art historian is at home with his young daughter Lola, watching the popular children’s film Stuart Little, when he notices a painting in the background that shakes him up so much, he almost drops his daughter from his lap. It appears to be a missing masterpiece by the Hungarian avant-garde painter Róbert Berény: Sleeping Lady with Black Vase. Unable to believe his own eyes, Gergely Barki, had only ever seen a faded black and white photo of Sleeping Lady with Black Vase taken in 1928 before it went missing without a paper trail in sight. As a researcher at the Hungarian National Gallery, Barki knows his Berény, and is certain that the prop cannot be a print or copy, given the obscurity of the artwork.

He swiftly embarks on a mission to track it down and ultimately finds the original painting, which had indeed ended up as a set piece in a popular Hollywood kids movie nearly a century later. The lost painting was recovered and made its way home, all thanks to Barki, a researcher at the Hungarian National Gallery, who also doubles up as a missing art detective on the mission to track down lost Hungarian masterpieces (more on that later). Let’s tumble through this strange-but-true art history mystery that wouldn’t feel out of place in a Wes Anderson film.

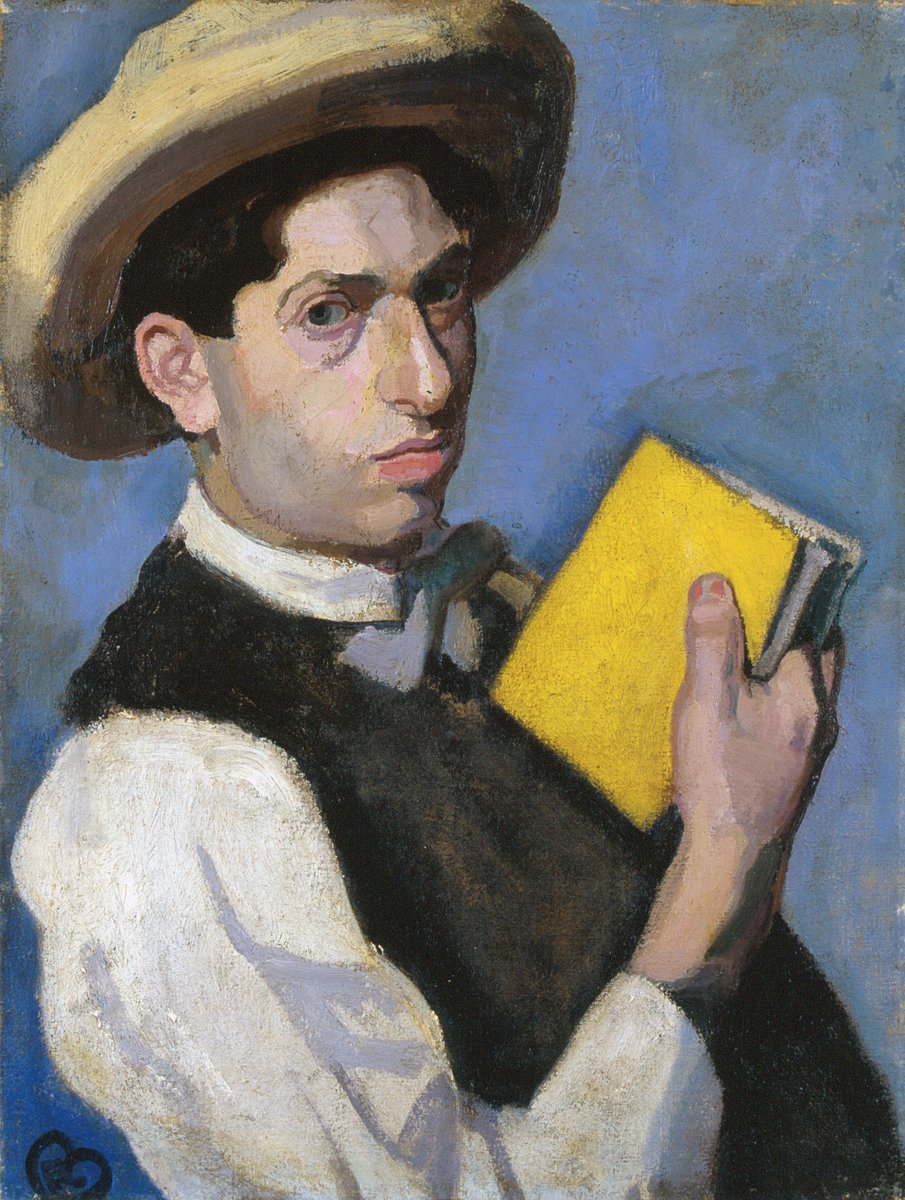

For those who don’t know much about Hungarian art history, Róbert Berény is quite a big deal. He was a core member of the pre-First World War avant-garde movement known as The Eight, a group inspired by the Fauves and Post-Impressionists such as Matisse and Cézanne while drawing influences from the Cubists and Expressionists. In fact, Berény studied in the Académie Julian in Paris in the early 1900s, and as a young artist, he moved through Paris’s exciting artistic circles; he’d go on to exhibit alongside Matisse, befriended Gertrude Stein, and at some point, he even hosted the Hungarian composer Bartók Béla for Christmas. His portrait of the reclusive composer was one of the most celebrated pieces from his early career. Having been immersed in all the hottest art trends in Paris, Berény would bring his knowledge back to Budapest to share with his fellow Hungarian avant-gardes. He’s also referred to as one of the Hungarian Fauves, a pioneer in the movement back in his home country.

Róbert Berény was quite the character. In an interview with The Guardian, his grandson Thomas Sos said his grandfather was quite the Renaissance man, who not only painted but was also a psychoanalyst (he was even an acquaintance of Sigmund Freud and sometimes had him over for dinner), a composer, and an inventor.

“He had a magical persona and even registered several patents for movie projectors at the German patent office,” Sos told the Guardian.

In 1919, Róbert Berény designed recruitment posters for Hungary’s short-lived communist revolution as leader of the department for painting in the Art Directorate. He had to flee the country in 1920, along with several artists and writers associated with the regime, when the short-lived communist state, the Socialist Federative Republic of Councils in Hungary (lasting only 133 days), collapsed, first going to Vienna and then to Berlin. He led an adventurous life in Berlin, where he’d even had a brief romance with Marlene Dietrich. Some rumours even circulated that he also had a fling with Anastasia, the daughter of Nicholas II, the last Tsar of Russia. He would also meet his second wife, cellist Eta Breuer, at a gathering here, who would go on to model for the lost painting.

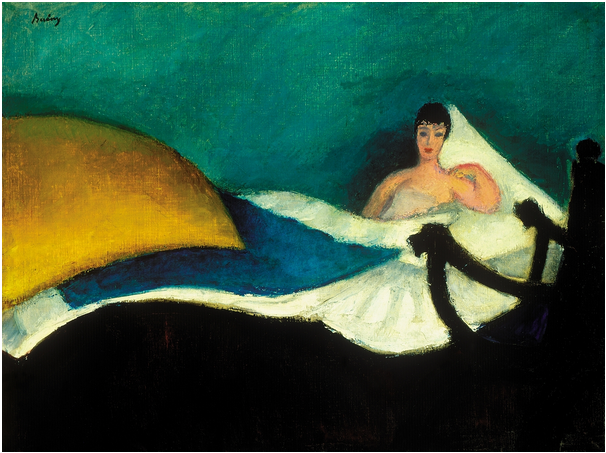

Eta was Róbert Berény’s muse, he painted her obsessively, and she features in many of his paintings. His paintings with Eta were deeply personal, but their avant-garde style made them fashionable and in demand. Berény moved back to Budapest in 1926 with his new wife in tow, and he likely painted Sleeping Lady with Black Vase between 1927 and 1928.

We don’t know much about Sleeping Lady with Black Vase, just that it was painted in his home in Budapest and was also exhibited a couple of times before it went missing and popped up in a Hollywood children’s film. It was first shown in the Ernst Museum and then again at the National Salon at an exhibition run by the Munkácsy Guild – this final detail is important, so remember that. After this last exhibition, this is where the trail gets cold until it somehow pops up again in the United States almost a century later.

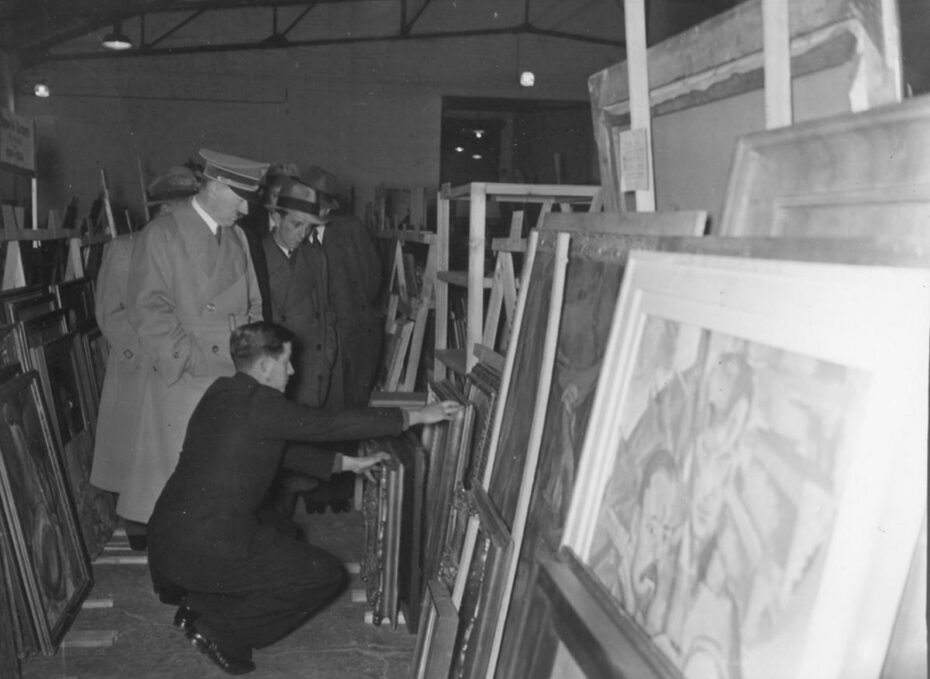

Berény stayed put in Hungary for the rest of his life. He lived in a dilapidated hundred-year-old villa in Városmajor, a neighbourhood in the northern part of Budapest on the western side of the Danube (in Buda). He wasn’t poor but struggled to keep up with the mansion’s repairs, which charmingly decayed around them. It even reached the point that he had a dinner party, and the plaster from the ceiling fell next to his soup bowl. Róbert Berény just moved the table a bit forward, and the dinner party resumed. However, since they couldn’t let the house fall apart around them, they took out another loan to deal with it but struggled to repay it. They were evicted in 1941, and because they were Jews, they were also forced into hiding. Not much is known about what happened to them under the Nazi occupation, but many of Berény’s paintings disappeared or were destroyed at this point. So it’s also possible that Sleeping Lady with Black Vase could have fallen into Nazi looter hands and begun its mysterious journey to America around then too, but this is the least likely theory.

Berény’s atelier was destroyed towards the end of World War II. He became a teacher under the communist government at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts. He died in 1953, just three years before another momentous event would occur in Hungarian history. In 1956, the Hungarian Revolution against the communist regime and Soviet control may have only lasted 12 days, but it tore the country apart. Thousands were killed or wounded, and nearly a quarter of a million Hungarians, including Róbert and Eta’s daughter, Anna, fled the country.

Anna was a dissident in the 1956 revolution, escaped the Revolution in Hungary, and ended up in the United States, where she lived in poverty. Her mother, Eta, Berény’s muse, would smuggle paintings out to her one at a time so she could sell them and live off the money. This is another possible story of how the picture crossed Europe and the Atlantic, but there is little to no evidence that Sleeping Lady with Black Vase took this route to the States.

Gergely Barki – who spotted the painting in Stuart Little in the first place – had another theory. He believed the painting was sold at the exhibition organised by the Munkácsy Guild in 1928, most likely bought by someone also Jewish, who fled the country before or during World War II. And, like many Hungarian masterpieces, it ended up in a different part of the world following war, revolutions, and the general chaos of the 20th century.

Barki was on a mission to track down the painting. Not only would he recover a piece of Hungarian art history, he could also amass even more clues about its history. So, he sent 40 to 50 emails to everyone involved with the Stuart Little film, including the creators at Sony Pictures and Columbia Pictures. He thought he was emailing into the void until he got a reply two years later from the former set designer who worked on Stuart Little (who remained anonymous to all the press).

She had bought the painting for $500 from an antique shop in Pasadena, California and thought its elegant and avant-garde aesthetic was fitting for the living room of the Stuart Little family. The painting did the rounds on various sets, making a guest appearance on some soap opera episodes, like Family Law. However, the set designer was utterly unaware of the painting’s value, but something about it spoke to her and had eventually bought the painting from the film company and hung it up in her apartment in Washington for years.

A year after Barki and the set designer set up an online correspondence, the Hungarian art historian travelled to the States and met up with her in a Washington D.C. park by a hot dog stand. Barki told her about the artist’s history and the painting, but there was one more thing he needed to know to be sure. He got up and asked the hot dog seller if he could borrow a screwdriver. He removed the protective backing from the frame, and there it was: The 1928 stamp from the Munkácsy Guild. The lost painting by Róbert Berény had been found.

Not only had the missing painting been uncovered, but it eventually made its way back home. The owner sold the painting to a private collector after she left Sony, and the collector brought the picture back to Budapest, where it was sold through the Judit Virág Gallery on December 13, 2014, for $285,700. The owner of the gallery, art historian Judit Virág, described the painting as being the perfect synthesis of European painting from the 1920s, containing the looseness of French trends, German strictness, and art deco elements, while also citing the colours of Dutch and Russian avant-gardes. How the Sleeping Lady with Black Vase was rediscovered has made it one of the most famous Hungarian paintings today.

Its six-figure price tag was a pain point for one art collector, whose part of the story is worth adding to the epic journey of Sleeping Lady with Black Vase. Before it came into the hands of a Hollywood set designer, Michael Hempstead had bought the painting in the mid-1990s from a charity auction at the St. Vincent de Paul auction house in San Diego. Someone had donated the Sleeping Lady with Black Vase, so Hempstead bought it for the shockingly low price of $40. He later saw that Berény’s paintings were going for $400 to $600; a friend referred him to the antique shop in Pasadena, where he sold it for $400, where the Stuart Little set designer would in turn buy it for $500. Although he never got to own the Sleeping Lady with Black Vase again, he told The Guardian he was still proud to have played a part in its story, “I helped it on its travel to Pasadena and on the movie. I am happy to be a part of its history.”

However, its story before Hempstead and how it made it to San Diego from Budapest is still a mystery. Barki says it offers an important lesson. “Researchers must always keep their eyes open, even when they are not concentrating on their work. Ever since I also watch films differently,” he said.

Barki never profited from the discovery of the painting, but writing a biography on Berény added extra depth to the history of the artist and his famous, missing painting. It’s also not the first time Barki has located a missing Hungarian masterpiece. In fact, you can think of him as kind of like a Hungarian art historian Indiana Jones, as he’s been tracking lost paintings across the globe. He’s found other paintings hidden on the backs of other paintings, under people’s beds in San Francisco. He has even gone to Sydney for a painting after an Australian widow of a man who bought a picture from the Jewish-Hungarian Fauvist and also a member of The Eight-, Desiderius Orban. The artist emigrated to Australia in 1939 after he saw the Holocaust coming and got as far as he could from Hungary.

Barki would put missing pictures in a magazine and even up in a separate salon at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest called WANTED, where the public could help him recover lost Hungarian works. He hung a photograph of another missing painting dating back to 1909, Red Nude Sculpture II by Béla Czóbel, and on opening night, an old lady walked in with the painting that matched it. The story may continue. As Barki continues to hunt down missing paintings.