No matter how long you’ve been in France, there will be few other moments in your life that feel both as culturally significant and stressful as your first ever game of pétanque.

The second the rain clouds clear over France in early spring, you can bet a boule will be thrown. There are a handful of diehard pros who play all year round, but this outdoor ball game is inherently suited to summer, requiring sand, sun and – if you’re a true native – pastis to play. As such, it will come as no surprise that it is largely associated with the glittering Mediterranean coast of the French Riviera – that, and the fact that it is acknowledged to have been invented there around 1907. But that doesn’t mean it is exclusively a southern sport.

According to the game’s official governing body, the Fédération Française de Pétanque et de Jeu Provençal, there are over 300,000 registered pétanque clubs in France. The entire country is teeming with players young and old, professional and amateur, enthusiastic and evangelical, and the capital is no exception. Swatches of sandy terrain flank the waterways and patchwork the parks. Everywhere you look, boules fans are catered to. Pétanque to France is perhaps what baseball or basketball is to America – to the extent that a bid was made to enter it into the 2024 Paris Olympics.

Variations of hand-ball games have existed since the invention of recreation itself. The official pétanque rule book is 12 pages long, but as far as we can tell, it mostly details uniform regulations.

The rules are simple. The origin of the name “pétanque” defines the sport: pieds tanqués derives from the French for “anchored feet”, the stance players must adopt within a demarcated zone before throwing a palm-sized metal ball as close as possible to a wooden marker, known as a cochonnet. The boule closest to the cochonnet wins the thrower’s team a point, and the boules are collected and thrown until one of the teams – ranging from one, two or three players – reaches 13 points in total. Throw in some dappled sunshine and a couple of cool drinks, what’s not to enjoy?

The best way to learn is to observe people who know what they’re doing. We suggest you make your way to a nearby boulodrome – a fenced-off section found in most of the city’s public parks. These crop up everywhere from a Roman amphitheatre to the regal, tree-lined gardens of Palais Royal. Even the Assemblée Nationale has its own team colours. However, some of these inner sanctums can be reserved for card-carriers only – especially the ones tucked away in secret gardens of the city – and it’s no mean feat getting your hands on a membership. Ironically, given the deceptive simplicity of the rules, the five bullet points describing how to register are not as straight-forward as they seem.

First of all, you have to pick a team. Technically, you can only join a club located in the same arrondissement as you – which also means you need to be a French resident. With over 50 clubs registered in Paris, this shouldn’t pose a problem. But we have our hearts set on Club Lepic Abbesses Pétanque – CLAP – in the historic heart of Montmartre…

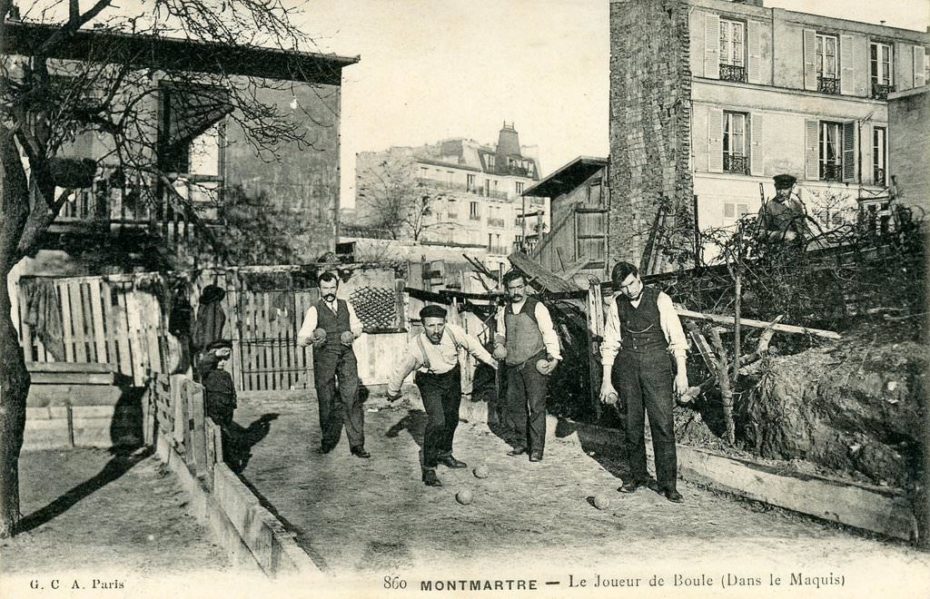

Locals have enjoyed turning the shady parks and cobbled streets behind the Sacre Coeur into improvised terrains since the beginning of the 20th century, but this particular club was officially founded with a fixed address on Avenue Junot in 1971. Surrounded by typically tall buildings, this secluded boulodrome has got to be one of Paris’ most picturesque. Its trees and pocket-sized club house are lovingly tended to – no doubt appreciated that extra bit more following a four-year legal battle to resist the space being developed into a car park in the early ‘80s. As well as being a testament to the French’s passion for pétanque, CLAP represents a notable number of female players for what is generally a male-dominated sport, encouraged by the current club president, Catherine Moureau.

To obtain membership, you need to visit the club house at the start of the season, which is in January, to pick up a subscription form. CLAP only accepts 250 members at a time, so it’s possible you will have to hold out for next year if they’re at capacity! Once you have filled the two-page form out, you need to return it complete with a recent passport photo, a cheque for 70€ and a medical certificate signed by a doctor declaring you’re fit to play.

If you’re still in the early stages of your sporting career and not yet a fully-fledged pro, you can generally slip into a boulodrome while a competition is taking place without a fuss. Here, you’ll find it abuzz with games zigging and zagging this way and that, heads set at acute angles. You’ll see players position themselves within a rubber hoop on the ground, carefully line up every boule before releasing, and swoop in on the resulting formation to see whether the score has been altered. At this point, tape measures materialise to assuage doubt.

This is what I found when I happened upon an inter-club over-55s doubles tournament. As a clear outsider – one of the few women and the youngest to boot – some members of the JBBC struck up conversation with me. I learned that most of the team have been had been playing casually for decades, but only signed up to a club when they retired. They came from all over the world but found their proclivity for pétanque here in Paris. When it was their turn to step into the circle, they invited me to join them on the far side of the terrain to watch them play.

They made it seem both effortless and fun, until an altercation broke out. Somebody had thrown somebody else’s boule. Why was this a problem? I asked my fellow spectator, a member of the JBBC who didn’t meet the age requirements for this match. “These are bespoke boules,” he explained. This was a revelation. The pros’ games are strictly BYOB: the diameter, the weight, even the engravings of their balls are tailored to them. “If you want to play properly,” he told me, “you have to stop playing with leisure boules”.

Feeling prepared to play, but not wanting to commit to the “reasonably cheap” 80€ starter set recommended to me, I instead headed to a nearby institution that lends out leisure boules for free. Bar Ourcq in the 19th arrondissement has been a stalwart ball provider for decades. Whether the demand or the owners’ generosity (and take-away beers) came first is hard to say. This service actually exists all over Paris, such as Ma Salle à Manger on Place Dauphine, as well as a number of indoor pétanque bars that have appeared across the city in recent years.

Borrowing a set of boules has become so easy, it’s hard to imagine how anyone can pass through the city without finding themselves as I did: on the busy banks of the Canal de l’Ourcq amidst large groups of habitual fair-weather players, attempting my first ever game of pétanque. My teammate had got us to a 12-12 tie break, and now it was all down to me to take us to victory. There’s an expression in pétanque culture that, in this moment, took on a new degree of importance: alors, tu tires ou tu pointes? Should I aim straight for the cochonnet, or strategically knock out a rival? I looked at it, surrounded by metallic bodyguards in tight formation. From here, I couldn’t see the markings that differentiated my team’s boules from my opponents’, but instinctively I knew what I had to do. My feet anchored to the ground, I mustered all that I had learned over the past week. I lifted the boule, lined it up with one eye closed, swung my arm back and forth, describing a perfect semi-circle, and released my shot.