Debutante balls, or cotillions, are a centuries old tradition with roots in Europe as far back as the 1700s. The word “debutante” translates to female beginner in French, and refers to a young woman making her debut into polite society. The first of these lavish events was held by King George III in 1780 in honour of his wife, Queen Charlotte. For the English aristocracy, however, this practice was a glorified matchmaking service used to announce a young woman’s marriageability to eligible bachelors. By the 1800s the debutante ball had migrated to America with the first ‘Christmas Cotillion’ taking place in 1817 in Savannah Georgia. Just like their European counterparts, upper class white American families used the balls as a means of presenting their daughters in hopes of finding them suitable partners, usually of the same social caste. So for many the term ‘debutante ball,’ may conjure up images of Bridgerton or genteel southern belles from affluent families, but debutante balls actually have a long and storied history in African American culture as well.

The first Black ‘debutante ball’ to be recorded by a newspaper actually took place in 1778 in New York. According to Taylor Bythewood-Porter, curator of a museum exhibit on the culture of African American debutante balls, these events were known as “Ethiopian Balls.” At these gatherings, the wives of free Black men serving the Royal Ethiopian Regiment would mingle with the wives of British soldiers. The first official African American debutante ball would take place in 1895 in New Orleans, a city which had a notably large population of free and upwardly mobile Black people at the time. These numbers only grew steadily with the eradication of slavery several decades prior. A distinct upper class had begun to flourish amongst the Black community and with it, a number of class-based practices, organisations and clubs.

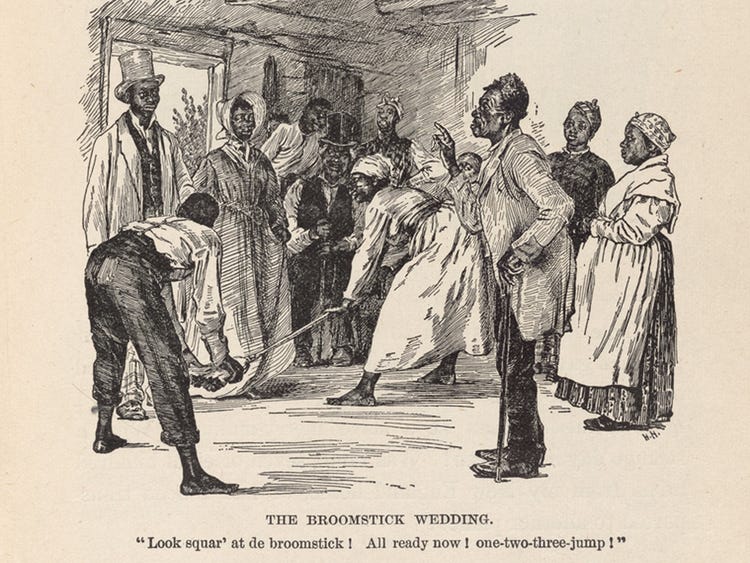

Black Americans have often had to create and carve out space for their own rites and rituals in a society that would not acknowledge or make room for their native customs. For example: the custom of “jumping the broom” was a common practice amongst slaves who did not have the legal right to get married. In the Black church; funerals are often referred to as ‘celebrations of life,’ and nowhere is this more evident than in New Orleans, where jazz funerals turn the tradition of mourning on its head with lively music, dancing, and parades. Many of these practices are an amalgamation of West African, Haitian, Anglo American, and English traditions. This is reflective of American culture itself which has often been influenced by various English, French, Latin American, and even Indigenous customs. The same is true for debutante balls as well.

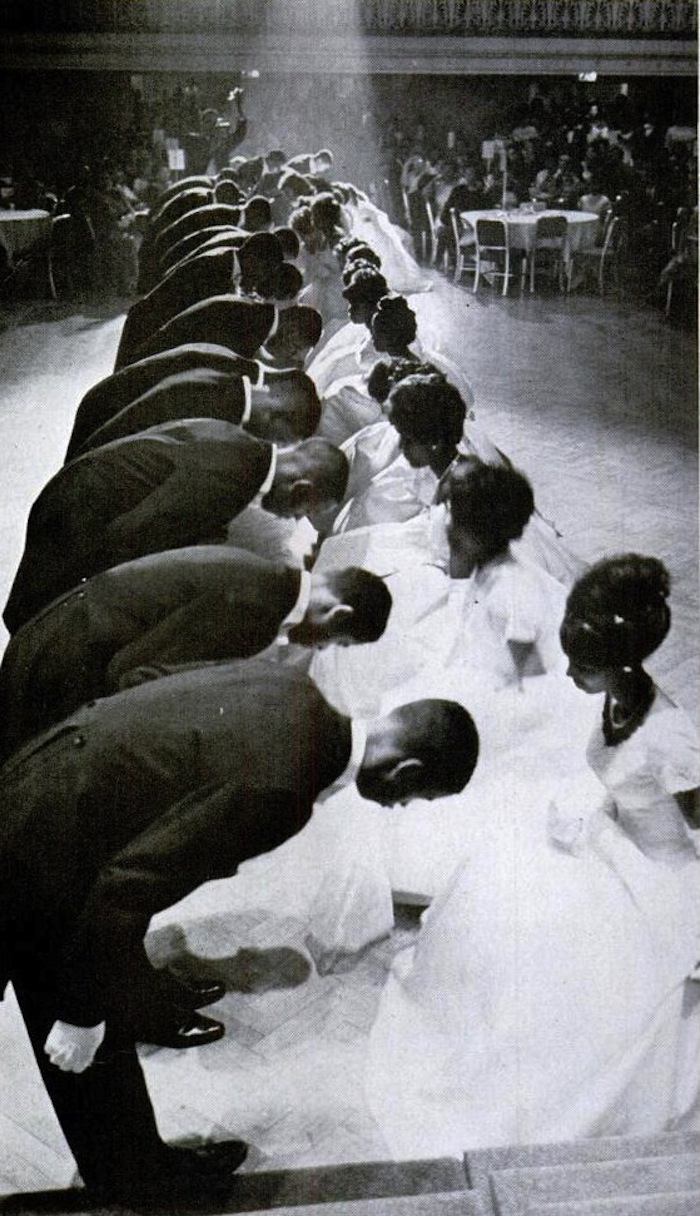

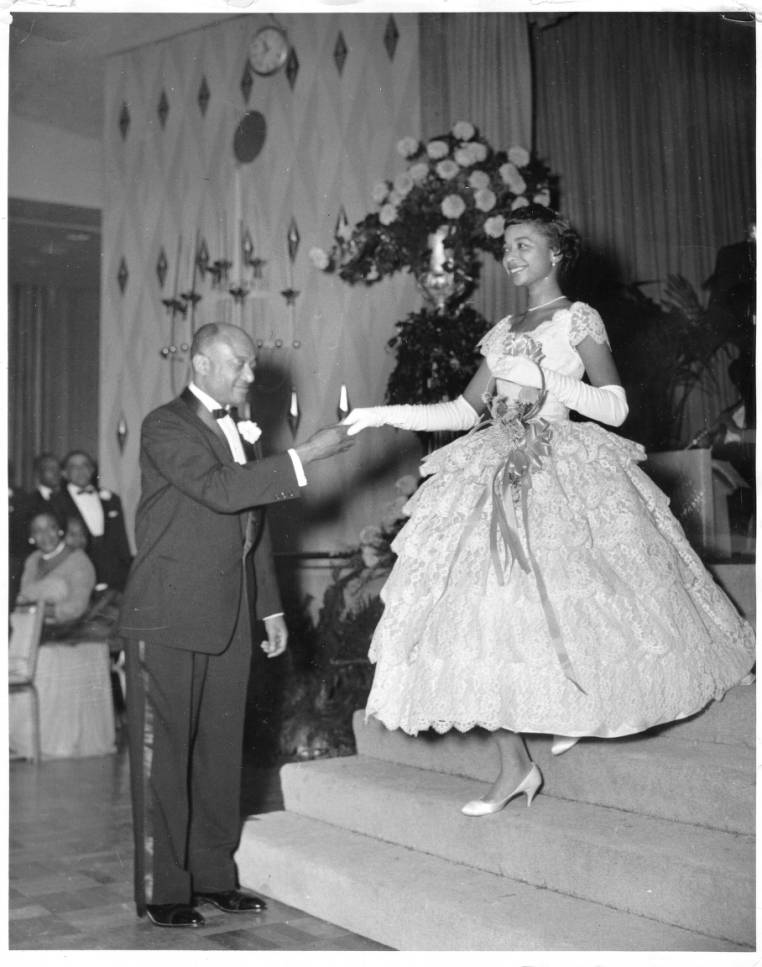

Black balls and cotillions were usually funded by social groups and institutions such as: Black churches, Links, Jack & Jill, and the 20th Century Onyx Club. These all-Black balls served a different purpose from that of their white counterparts in that they were in some ways an effort on the part of wealthy African Americans to show off the Black community in a dignified manner. They combatted the stereotype of broken Black families by having the fathers proudly present their daughters, which in turn disputed the damaging misconception of Black women being non-virtuous.

During these events, young Black women were encouraged to demonstrate good manners, grooming, and social etiquette. The skills they learned in preparation for their debuts were meant to help prepare them for the world beyond the protection of their social circles, particularly, wider white American society.

These events were also used as an opportunity to showcase the achievements of young Black women and by extension, their families. With more Black women entering academic spaces between the 1940s-1960s, an emphasis was placed on education, networking, fundraising and community outreach. Incentives such as scholarships and grants were being given to participating “debs” with lofty career and educational goals.

The fundraising efforts of these events were meant to teach the young debs the importance of building wealth and giving back to their communities through charity. Although these may have seemed like noble causes however, for a large part of its history, Black debutante balls have been accused of classism and exclusion. These events kept wealth and opportunity isolated within the ranks of the upper class; shutting out young Black women from disadvantaged backgrounds who may have benefitted from participating.

According to Ruth Terry’s interview with former deb Heather Joy Thompson; there are administrative fees to participate, ads must be bought in the program books, and families have to purchase a table at the ball. There are also specific requirements for the dresses which can amount to a hefty wardrobe budget considering the rarity of the items such as crinolines for the skirts. For underprivileged families, these expenses may simply be too costly, along with the time needed to properly prepare for a ball.

In more recent years, with the attempted revival of Black cotillions, there has been a conscious effort to make debutante balls more affordable and accessible to Black people of different socio-economic backgrounds. Naimah Cochrane, organizer of the Renaissance Debutante Program, stated, “We’ve had dresses donated before, and people buy sponsored tickets we can give to those who can’t afford them. We just ask families to come talk to us and be transparent.”

In a 2019 article written by Hannah Covington for Star Tribune, former high school senior, Jadyn Hayes, commented: “It all seemed so pretentious and uppity. Now it seems really important to me to wear the dress and gloves. I am representing something important — Black history.”

Retired District Judge Pamela Alexander stated: “African-American girls don’t get a lot of positive reinforcement or feedback. They’re not told that they’re beautiful. This gives us an opportunity to showcase them.”

In recent decades, debutante balls have fallen out of favor as the newer generations begin to embrace more lax gender roles and educate themselves on the negative effects of classism. However, in the Black community, there still remains a certain fondness for and deeper understanding of the long tradition as something more than a display of classist exhibitionism. For Black women hoping to preserve the tradition of the debutante ball, there is a desire to continue to showcase the talent, intelligence, dignity, and beauty of the Black woman.

We’ll leave you with the one and only Beyoncé and her “Brown Skin Girl” video, an incredibly moving tribute to the history of Black debutantes in the U.S.