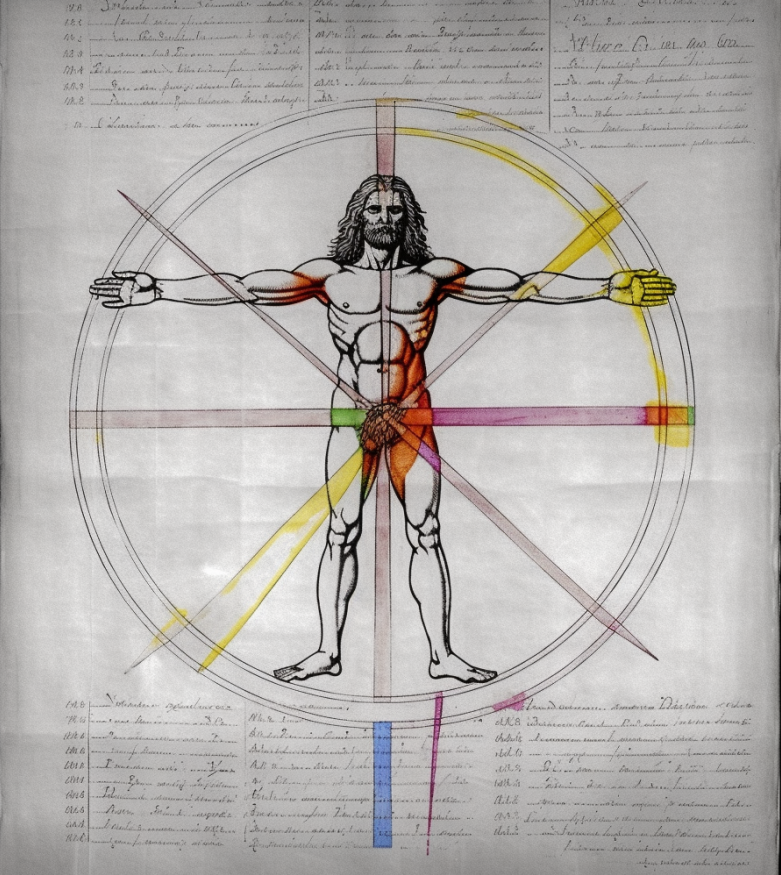

While you’re almost certainly familiar with his unrivalled genius as a painter, inventor, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor or architect, there is a little-known aspect of Leonard da Vinci’s life rarely taken into consideration in the context of art history; one that could potentially paint the great master as an unrealised icon of LGBTQ history. Behind the brushstrokes of brilliance, Leonardo da Vinci was also very human. He was illegitimate, left-handed, vegetarian, heretical at times, quite likely had ADHD and dyslexia, and according to a surprising amount of scholars and academics, Leonardo da Vinci was also gay.

In Walter Isaacson’s fascinating tome of a biography about the artist, he details how just a week before his 24th birthday in April 1476, Leonardo da Vinci was arrested following an anonymous tip that he’d been engaged in sexual acts with Jacopo Saltarelli, an apprentice goldsmith who side-hustled as a sex worker. This act of publicly “outing” the painter is the only known historical document that exists regarding Leonardo da Vinci’s sex life. The unsigned written document was deposited to the town hall via a tamburo, a letter box typically reserved for the citizens of Florence to anonymously complain of “deviant” behaviour to the authorities. In this instance, the denunciation wasn’t specific to Leonardo da Vinci, but he was one of the four men accused of soliciting sexual services from Saltarelli, who was denounced by he sender for also dressing in black and being “party to many wretched affairs”. Although the accusation was anonymous, it didn’t go unchecked. The Officers of the Night, a Florentine court and division established in 1432 that focused particularly on sodomy and prostitution, investigated the accused men, investigated the accused men, but charges were ultimately dismissed (one of the accused had close ties with the powerful Medici family). Several months later, the same anonymous letter was sent in, this time written in Latin, but again the case was dropped again.

While some of the most celebrated Renaissance artists, such as Michelangelo, Donatello, Botticelli were believed to be gay (or at least had charges of sodomy cast against them at some point), there is nothing in writing beyond speculation that Leonardo da Vinci had male lovers. There is a more generally accepted (or convenient) case amongst academia, that concludes he simply chose to live an entirely celibate life. Having been so publicly accused of sodomy, putting his freedom and life at risk, it wouldn’t be surprising if the artist had sworn off pursuing romantic relationships. Some historians have theorised Leonardo to be more of an asexual inclination than a sexually active gay man. Da Vinci himself once wrote, “intellectual passion drives out sensuality”. But he also wrote statements in his journals such as, “Only love makes me remember, it alone fires me up,” and “I found myself in the past days, having (been) urged: If there is no love, what then…?”. He also wrote, “L’amore mi fa sollaz are” – “Love amuses me”.

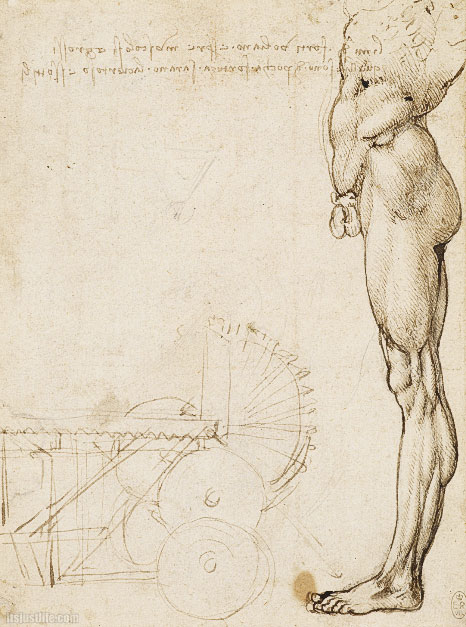

He appears to have been conflicted on the subject of sexual desire; in once instance describing genitals as “so ugly” that humanity would face extinction if it weren’t for “pretty faces, adornment and unrestrained dispositions.” Contrarily, he also kept a dedicated section in his notebooks entitled “On the Penis,” which humorously describes the penis as having a mind of its own and mused why it was considered a source of shame. “Man is wrong to be ashamed of giving it a name or showing it,” Leonardo wrote, “always covering and concealing something that deserves to be adorned and displayed with ceremony.”

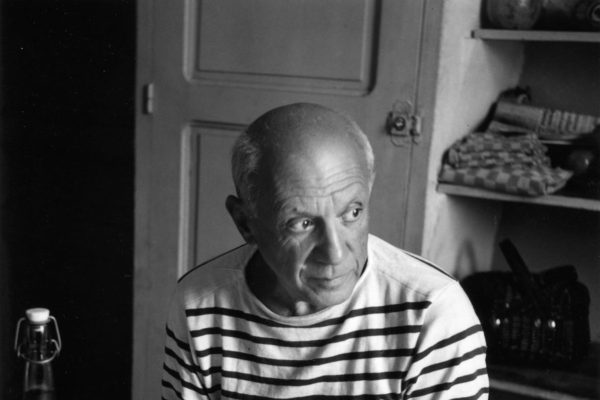

Leonardo was described as a man of beauty and grace, with a muscular build, extremely strong and handsome, and a flamboyant dresser. There is little to no historical documentation of any significant relationships with women and Leonardo was never married. It is well-documented however that Leonardo had numerous male companions. Even if they were not sexual, there is no doubt that Leonardo formed an intense bond with the men in his life.

Following the Saltarelli scandal, Leonardo da Vinci described his relationship with a young artist, Fioravane di Domenico of Florence, two years later as “my most beloved friend, as though he were my…” (the sentence was deliberately unfinished in his scribblings). Another of his early male companions was a musician, Atalante Migliorotti, whom Leonardo taught the lyre and accompanied to Milan but Atalante would later go on to have a successful music career and ultimately part ways from the artist.

In 1490, da Vinci’s friend and fellow Italian Renaissance Master, Giorgio Vasari, wrote: “In Milan, Leonardo took on as his servant Salaì, a pleasingly graceful and handsome boy from that city with beautiful, thick, curly hair which greatly pleased Leonardo, who taught him many things about painting, and some of the works attributed to Salaì in Milan were retouched by Leonardo.”

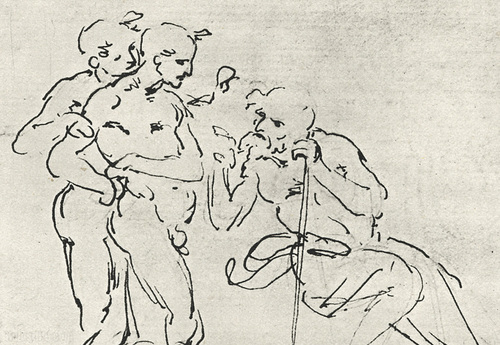

Leonardo’s servant was Gian Giacomo Caprotti, who earned the nickname Salaì, meaning “little devil”, as he was described as having the looks of an angel with a devilish smile. Caprotti was sent to Leonardo da Vinci to work for him as a servant when he was only ten years old. It’s speculated that if a physical relationship had developed between them, it was likely when he was older (we hope), but even if his servant were of a more respectable age, there would have already been a significant age gap between them. Plato’s Symposium celebrated the love between older men and younger boys, and Renaissance humanists idealised this viewpoint.

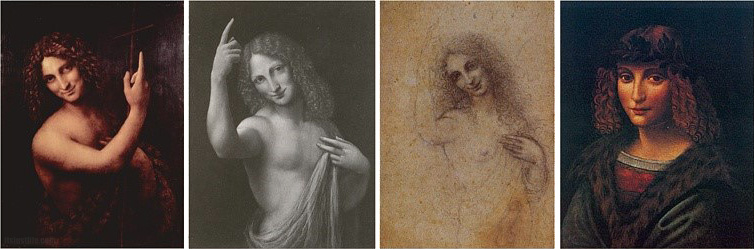

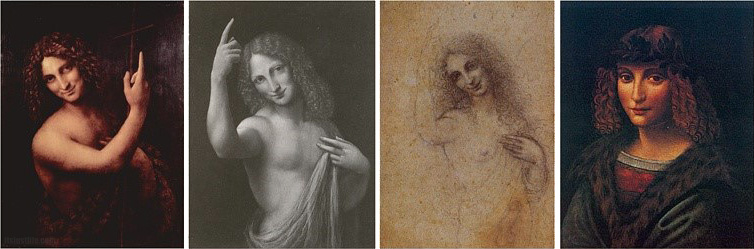

Whether or not their relationship with sexual, according to Vasari, Salaì remained by Leonardo’s side for 25 years and, of one thing we can be certain: Salaì was Leonardo’s muse. You’ll find his face in many of his paintings, like St. John the Baptist, Bacchus, and Angelo Incarnato (the latter being an erotic drawing of a young man with an erection).

The da Vinci archives also include several named (and nude) sketches of Salaì. Some even believe that Salaì was the model of the Mona Lisa – which Salaì actually inherited upon Leonardo’s death – but it’s a controversial claim that many historians refute. Salaì left Leonardo in 1518, but inherited several works and land from the artist following his death in 1519. Salaì would go on to marry but died in a duel in 1524.

In the early 20th century, Sigmund Freud psychoanalysed the famous artist, 500 years after he lived in his book, “Leonardo da Vinci – A Memory of his Childhood”. In classic Freud style, the paper argues its case using a childhood memory that Leonardo recorded when documenting the flight of vultures, to connect homosexuality to his relationship with his mother.

Leonardo wrote: “I recall as one of my very earliest memories that while I was in my cradle, a vulture came down to me, and opened my mouth with its tail, and struck me many times with its tail against my lips.”

Freud interprets this as a distortion of the memory of the mother suckling her child being replaced by the vulture tail, which represents a penis. Freud uses this memory to argue that while da Vinci was gay, he diverted his homosexuality into a more celibate form, channelling his energy into his art.

Da Vinci’s brushstrokes, once seen through a narrow lens, offer a kaleidoscope of possibilities, but can we add da Vinci’s picture to the grand gallery of LGBTQ+ icons? Given the historical and cultural context of Renaissance Italy, where homosexuality was generally condemned, da Vinci’s personal still life remains largely shrouded in mystery. This ambiguity serves as a reminder of the challenges in uncovering the hidden histories of LGBTQ+ individuals and prompts us to consider the presence of queer individuals throughout history. While da Vinci may not have been given the chance, there are however countless historically significant figures who openly identified with their sexual orientation and made significant contributions in advancing LGBTQ+ rights and visibility. And we must continue to celebrate them.