Plucking, shaving, waxing, epilating, threading, lasering – whatever preference one has for grooming body hair, we can probably all agree that most of the time, it would be easier if we didn’t have to do it all. And for a good part of Western civilization, underarm, leg, and pubic hair were simply expected parts of the naked male and female body until the 20th century. In Georgian Britain, pubic hair was actually a popular gift exchanged among lovers as tokens of affection; collected as a souvenir and even worn proudly like cockades in hats for good luck. But through the ages around the world, humankind has relentlessly been tampering with body hair and has always been a hot topic in life, literature and art.

For early mankind, a hair-covered body was a burden. Most of our blanketing body hair was shed in order to let us better chase prey across the scorching African plain. All was not lost though; hair was retained on the head to screen the sun, armpits and crotch to avoid skin-to-skin friction and fine follicles on the body and limbs to sense insects, dust or situational danger.

The ancient Egyptians practically invented razors: both men and women preferred to be – well, smooth as a baby’s bottom, and removed most of their body hair with sharp pumice stones, flint, seashells, beeswax and their own potions of hair removal cream. General cleanliness (lice was an issue) may have prompted this and in fact, Nubian wigs made for far easier maintenance. The ancient Egyptian priests of both sexes shaved every day to appear ‘pure’ in front of the gods. Cleopatra VII used a method not unlike today’s waxing for removing her pubic hair, with a sugar mixture and cloth strips.

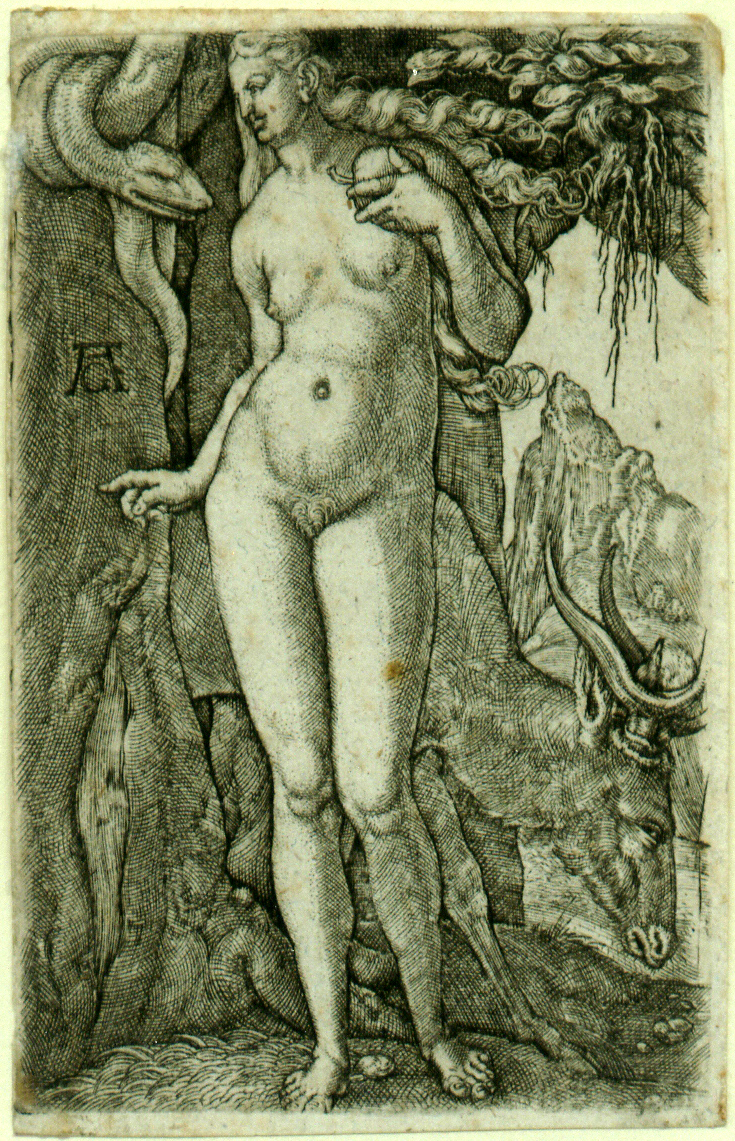

The ancient Greeks didn’t care much for overgrown lady gardens either and took the view that female body hair just wasn’t civilised. They plucked and singed until there wasn’t a hair in sight – see their perfectly smooth hair-free marble statues that would influence our perception of the ideal body for centuries to come. Aristocratic Roman women reached for pumice stones, tweezers and depilatories; they too associated hair-free bodies with an elevated state of purity and superiority. Given the popularity of their baths and communal toilettes display was not a chance event. It was perhaps a result of infestations with parasites that both men and women chose to remove body hair. In Greek culture, these practices led to the general assumption that female body hair in particular was uncivilized or low-class. Ancient Persian women resorted to hair-removal sugaring potions, a gentle way to extract the hair leaving silky smooth skin. (Sugar would not reach Europe until the first millennium AD.)

Fast forward to the Middle Ages and the trend for pubic hair (despite pubic lice and other nasty pestilences being rife) was to remain au naturel, as being shaven came with the undesired connotations of being a ‘lady of the night’. It is recorded in the 1450s that some sex workers did shave it all off to get rid of lice and the sores left by syphilis and gonorrhea. Prostitutes in 16th century England typically wore intimate toupees called ‘merkins’. In the Elizabethan era, shaving fashion still wasn’t a priority for women, already burdened with layers of cumbersome petticoats, frills, corsets and cloaks.

However, Queen Elizabeth I, style icon of the day, focused on her eyebrows and had these plucked to oblivion, then proceeded northwards to give herself the desired long forehead and oval shape. It was around this time that literature began boasting recipes galore for removing unwanted hair; The Exploress (Oct 2019) cites a hot tip from a publication called How to Remove or Lose Hair from Anywhere on the Body (1530s): “Go to a bath or a hot room and smear medicine over the area to be depilated. When the skin feels hot, wash quickly with hot water so the flesh doesn’t come off.”

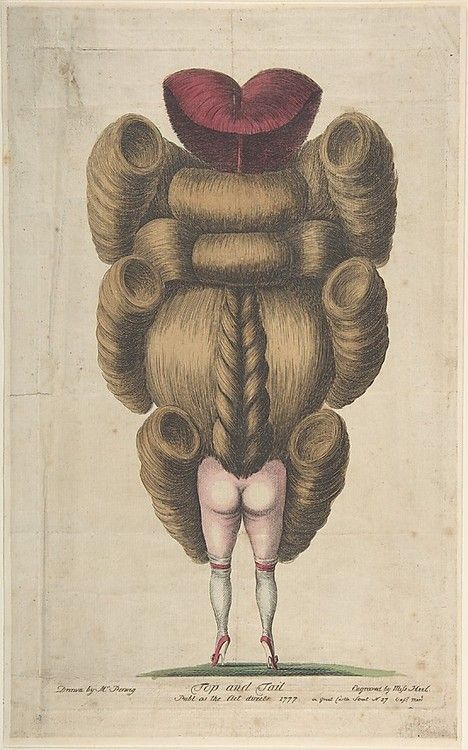

During the 18th century Georgian era in Britain pubic, hair became the stuff of fetish culture: lovers collected each other’s nether region hair and in a display of virility, often wearing these souvenirs as trophies in their hats. Pubic hair also played a key role in many of the secret 18th century male sex societies such as at the Beggar’s Benison in Fife, Scotland. So much so that the president of the Beggar’s Benison wore an exotic wig (his ‘crown’) woven from the pubic hair of one of King Charles II’s mistresses, donated on one of his visits. The upkeep of the wig required members to keep harvesting ‘curls’ from their own mistresses. Centuries old slang used for describing the hair of ones nether regions included creative and poetic codenames such as ‘thatched cottage’, ‘mossy cave’, ‘gooseberry bush’, ‘tail feathers’ and ‘nether whiskers’.

While Victorian literature and art generally avoided intimate subject matters, some scholars reckon that Charles Darwin’s book “The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex” (1871) suggests women with scant body hair are more evolved and more sexually desirable. Contrarily, in the memoir, My Secret Life (1888) by Henry Spencer Ashbee, the narrator marvels over a Scotswoman’s thick red pubic hair: “the bush was long and thick, twisting and curling in masses half-way up to her navel, and it spread about up her buttocks, gradually getting shorter there”, he goes on to say, “bare of hair, those with but hairy stubble, those with bushes six inches long, covering them from bum bone to navel” and adds as an afterthought, “there is not much that I have not seen, felt or tried, with respect to this supreme female article.” In an erotic classic The Memoirs of Dolly Morton (1898) a protagonist’s spot allegedly sprouted 2-inch-long locks, “a thick forest of glossy dark brown hair”, with one man exclaiming, “but Gosh! I’ve never seen such a fleece between a woman’s legs in my life. Darn me if she wouldn’t have to be sheared before man could get into her.”

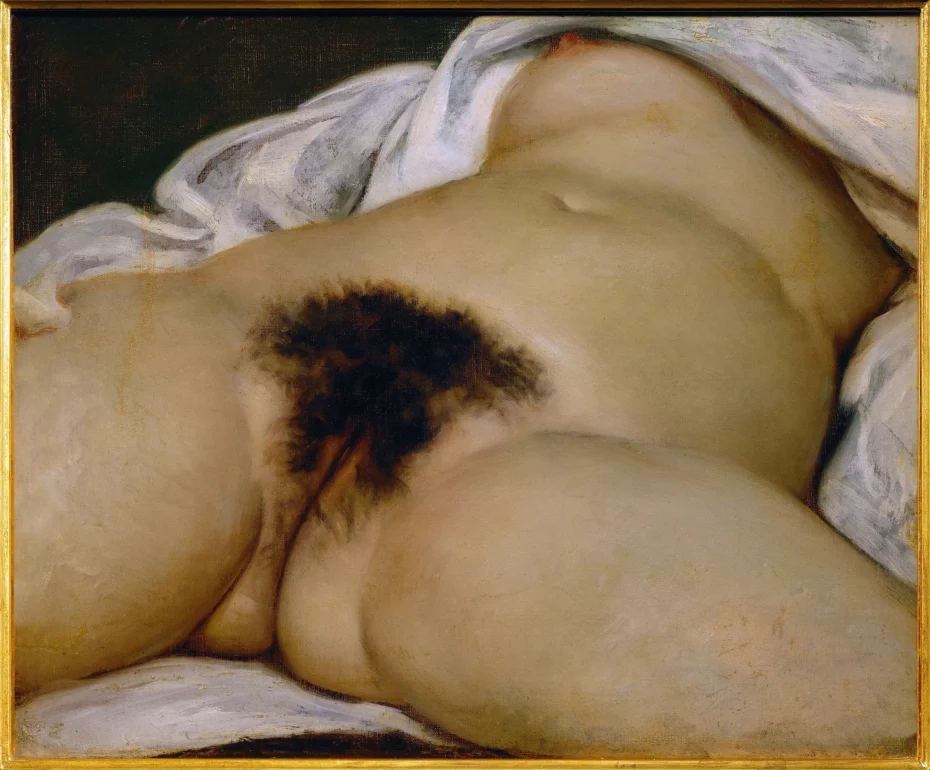

While a hairless body was a signifier of cleanliness, class and ideal beauty, writer and art historian Christopher P Jones notes that “the converse of this was the idea of women’s body hair as a sign of wild sexuality”. Enter Gustave Courbet and his controversial painting, “L’Origine du Monde” which broke barriers and “the taboo of representing pubic hair in art” which represented “a note of eroticism … and heightened sexuality.”

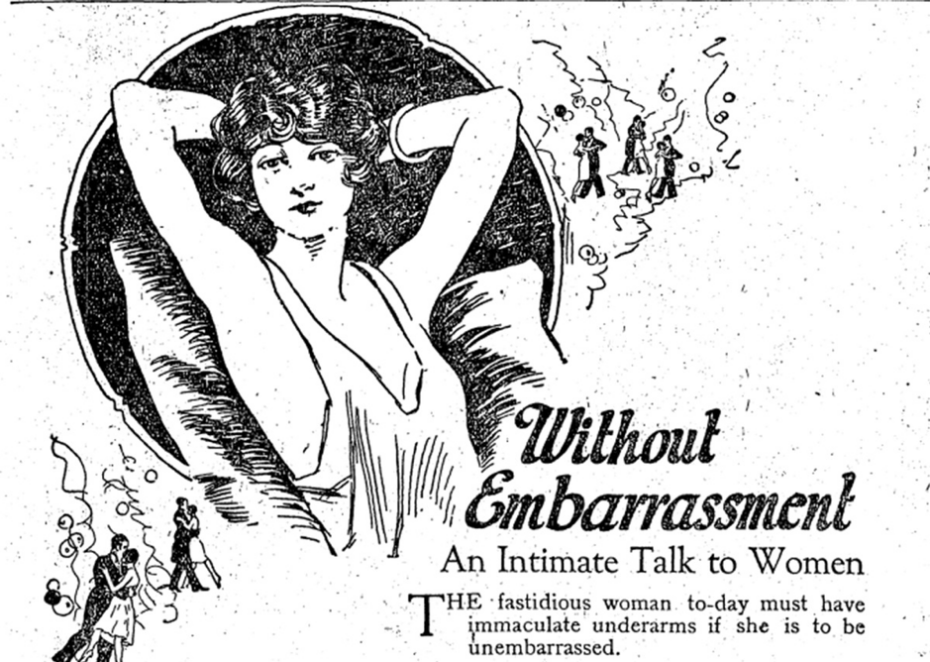

But from the 20th century, the wealthy elite in Europe started to enjoy holidays; a spa culture emerged, Turkish Baths were having a moment and with this emerged a greater awareness of ‘unsightly’ hair. From 1910, industrially produced safety razors became widely available. Cropped and sleeveless flapper frocks called for smooth legs and exposed armpits; the razor was an essential tool of this newfound freedom for women. In 1903, King Camp Gillette gave the world its first safety razor with a disposable blade and in 1915, came a version designed especially for women, the Milady Décolleté – a necessity for being feminine, classy and emancipated. The commercial world immediately cottoned on, the advertising, fashion, cosmetics and beauty industries launched a multi-pronged attack on anyone who considered an alternative to epilation or depilation. Barely established, WW2 bought a nylon scarcity and this made shaving even more popular or essential as propaganda campaigns told women to save her nylons and silks for military parachutes. Concurrently, bathing suits shrank to become bikinis and as the war raged on, those silky smooth, long legged pin-up girls became wartime icons. Throughout the twentieth century, to shift more and more products, commercialisation hammered home a message using anti-hair keywords such as ‘need’, ‘embarrassment’, ‘offensive’, ‘unsightly’ and ‘unclean’.

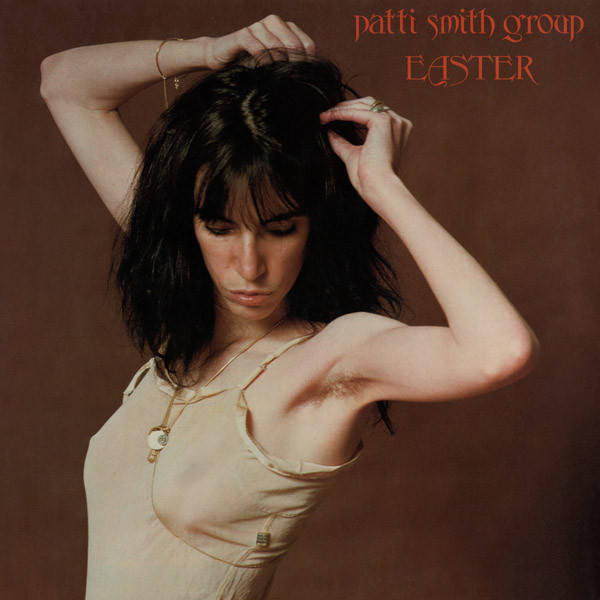

The sexual freedom, feminism and individual expression of the 1960s and 70s saw the rebirth of the bush and typically, the more hair you had the better. But it was short-lived, and despite Patti Smith giving us her best underarm bush on her 1978 album cover, the 1980s saw a return more naked, hairless flesh on the beaches as people became ‘body beautiful’ aware. The 1990s heralded in the Brazilian wax and TV series like Baywatch and Sex in the City reinforced the female shaving cult, while the feminist movements explicitly rejected shaving. Men’s health media followed this now very confused path, promoting perfectly smooth buffed bodies with not a chest hair to be seen.

To shave or not to shave? What’s been prompting us to reach for the razors and the lasers? As history tells us, body hair removal practices are about association and belonging, a function of following gender roles and displaying a perceived social status through an idealised notion of body image.

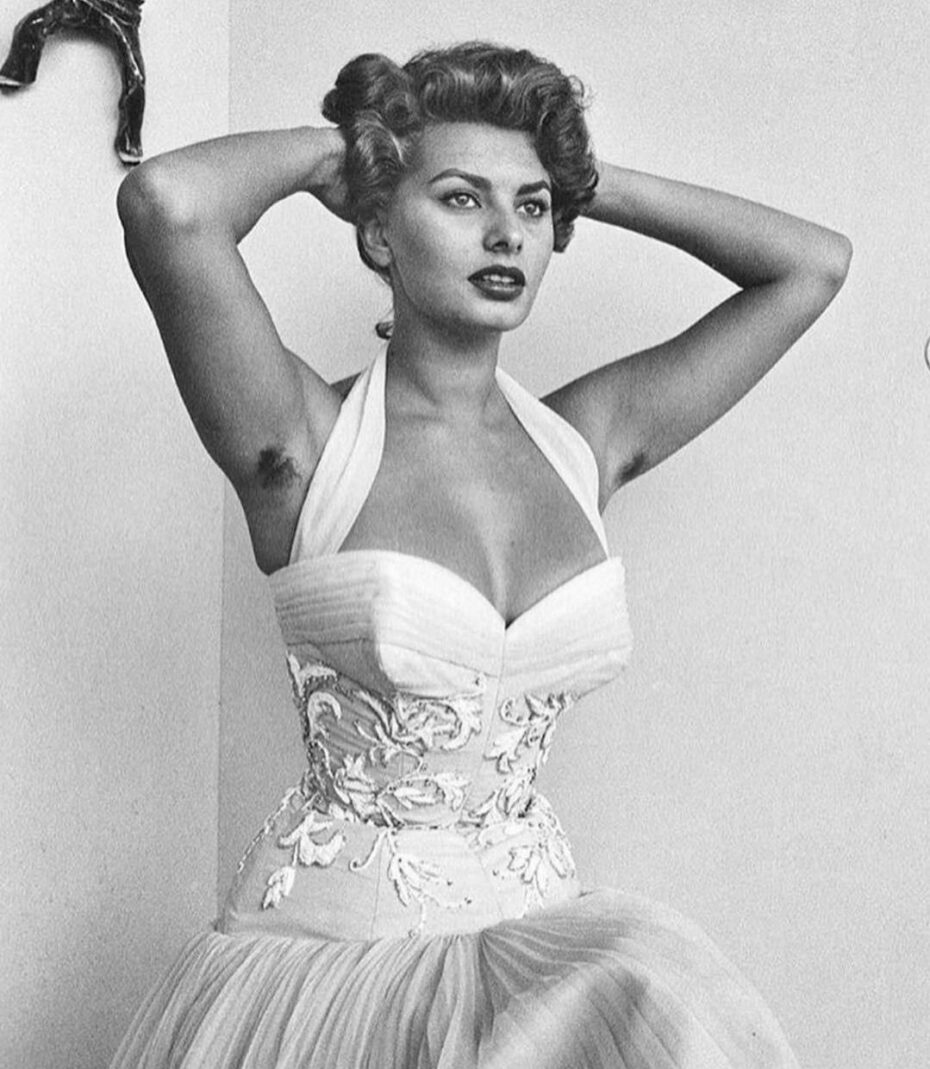

And with that, we’ll leave you with an image of Sophia Loren, who stood out in old Hollywood for choosing not to shave her armpits. While it’s often been chalked up to “differing cultural norms”, Loren was no dummy – but she was a free spirit and had no shortage of confidence. Just as Hollywood sex symbols were leading us into a new age of artificial beauty and the culture of cosmetic was becoming mainstream in the 1950s, Sophia’s natural beauty (and her iconic armpit hair) was perhaps the overlooked and missed antidote.