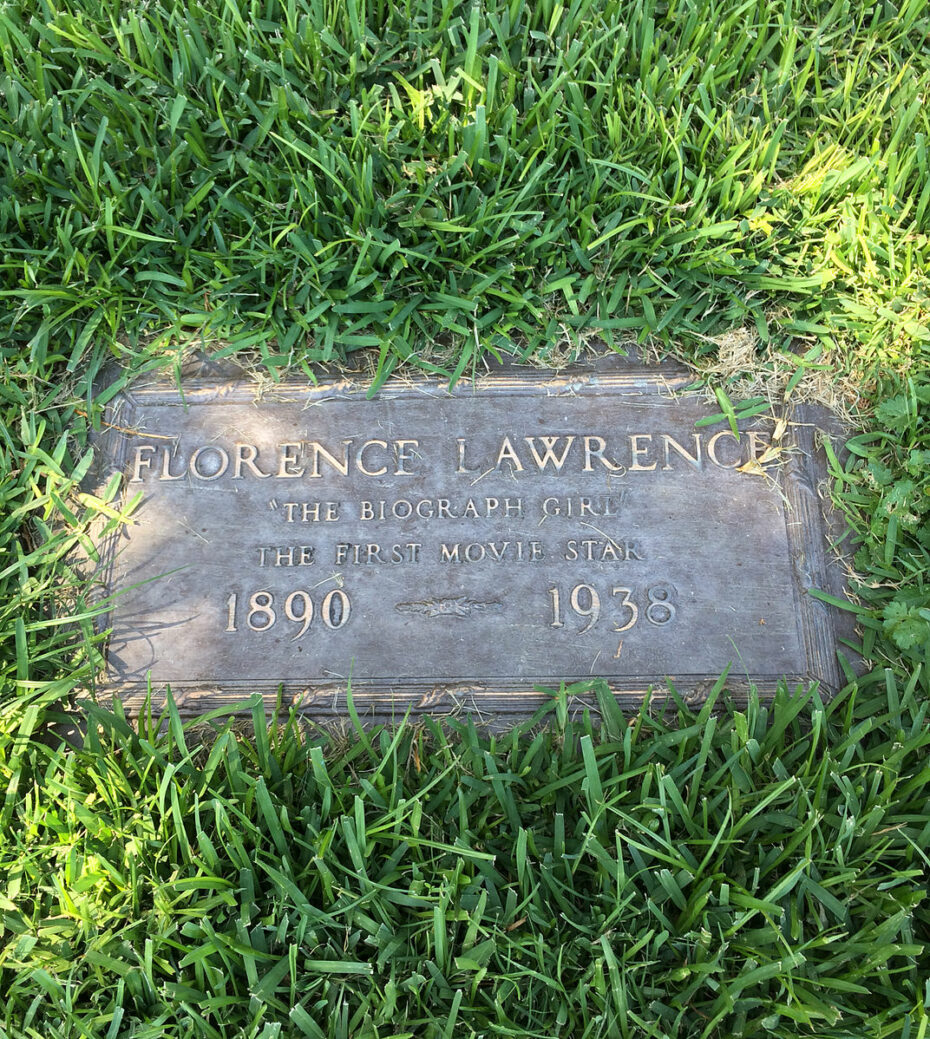

Picture this: it’s the early 1900s, the silent film era is still just finding its feet, and movie stars are as mythical as unicorns. Enter Florence Lawrence, the “first movie star”, who is about to embark on an epic career, spending the next three decades appearing in almost 300 films. Up until this point, no Hollywood actor has ever had their name splashed across the silver screen; they were merely faces in the flickering frames, credited only as “The Biograph Girl” or “The Vitagraph Girl”, after the film studios they worked for. But Ms. Florence, with her trailblazing charm, would change all that, and behind the scenes, she didn’t just sit around looking pretty. In her spare time, Lawrence used her smarts to invent a surprising list of patents, including the first “auto signaling arm”, which alone should have earned her a notable chapter in the annals of history. Her life story reads like a rollercoaster of glamour, innovation, and finally heartbreaking misfortune, that in the end, left her with nothing but an unmarked grave. Let’s roll the tape on Florence Lawrence.

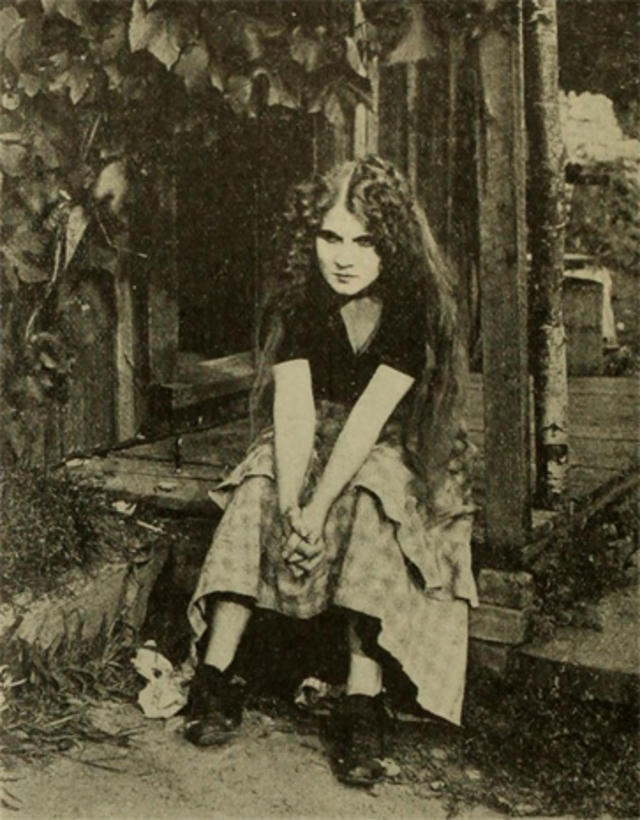

Born in Hamilton, Ontario, in 1886, Lawrence’s foray into the film industry was almost inevitable. With a stage mother like Charlotte Bridgwood, an actress herself, Florence was practically destined to perform. She made her stage debut at just three years old, touring with her mother’s company and learning the ropes of performance. She later began her career in 1906 with the Vitagraph Company, with whom she made 38 silent films, but her big break came when she joined Biograph Studios. Her performances in movies like “The Black Hand” (1908), one of the earliest gangster films, and “Rescued from an Eagle’s Nest” (1908), where she played a mother who battles an eagle to save her child, solidified her reputation as a versatile and captivating actress, earning her the nickname “The Biograph Girl.”

Lawrence’s entry into the film industry came at a time when actors were not credited for their work, known only as “the players”, and movies were often shown without titles. During those early years, studios feared that if actors became well-known and popular, they would demand higher salaries. Some actors even preferred the anonymity at a time when their career choice was still frowned upon in society. This practice kept Lawrence’s identity hidden from the public, even as her face became one of the most recognisable in the country. Audiences loved Florence, but they didn’t know the name behind the face — until 1910, that is, when she moved to the Independent Moving Pictures Company (IMP). The studio’s founder, Carl Laemmle, a shrewd businessman, saw the potential in promoting actors as stars to draw audiences. In a bold publicity stunt, he spread a rumor that Florence had tragically died. Once the gossip mills were churning, Laemmle revealed the dramatic truth: not only was Florence very much alive, but she was also signing with IMP. By publicly naming Lawrence, they broke the industry norm and set a precedent for the star system in Hollywood. Lawrence became the first American actress to receive billing under her own name, marking the birth of the movie star (she was long thought to be the first film actor in the world to be named publicly until evidence published in 2019 indicated that it was French actor Max Linder). Her name alone became a box-office draw, and she was often mobbed by fans.

We often forget that we have women to thank in large part for kickstarting Hollywood. A hundred years ago women were involved in nearly every aspect of production and held key positions in the industry. Did you know know that half of all the films copyrighted in between 1911 and 1925 were written by women? Florence not only acted but also took on roles behind the camera, directing and producing films. Her work ethic and creativity were evident in movies like “The Lady Leone” (1912) and “The Country Girl” (1915), where she portrayed strong, independent female characters, challenging the era’s gender norms. Florence was also a daredevil on set. She performed her own stunts long before it became fashionable, risking life and limb to make sure the action looked as authentic as possible.

This commitment to realism, however, came with a heavy price. In 1915, while filming “Pawns of Destiny,” she suffered severe burns and a fractured spine after a stage fire went horrifically wrong. Universal, her employer at thetime, refused to cover her medical expenses, leaving her financially and physically devastated.

But let’s not fast-forward to the tragedy just yet. Lawrence’s inventive mind was just as agile as her acting skills. Outside the glitz and glamour of Hollywood, she was something of a mechanical whiz. Her own mother had invented a type of windshield wiper. In the early 1900s, the advent of the automobile had introduced new dangers to the public and by the 1920s, road accidents had become a significant concern for everyone. Florence was a keen driver, particularly as driving had become a symbol of women’s liberation, but she was frustrated with the lack of communication tools between drivers. And so, instead of waiting for someone else to do it, she went ahead and invented the first “auto signaling arm,” a forerunner to the modern turn signal. She also designed the first mechanical brake signal, a vital innovation that alerted drivers behind her when she was slowing down. However, Florence, more artist than business mogul, never patented these life-saving devices. As a result, she received no credit or profit from her inventions, which became standard in automobiles worldwide.

Despite her groundbreaking contributions to both film and automotive safety, Florence Lawrence’s career never fully recovered after her 1915 accident on set. She tried to make a comeback, but the changing tides of the film industry and her mounting health issues made it an uphill battle. By the 1920s, she was largely forgotten by an industry that was moving on faster than a Model T.

In a cruel twist of fate, Lawrence’s life ended in despair. In 1938, plagued by chronic pain and depression, she took her own life using ant poison. She was buried in an unmarked grave, a stark contrast to the bright lights and adoration she once knew. It wasn’t until 1991, over five decades later, that the film community finally acknowledged her contribution, placing a marker on her grave that read, “The First Movie Star.” Her story is a poignant reminder of the fleeting nature of fame and the unrecognized brilliance that often goes unnoticed. But in her life, we see the glimmer of Hollywood’s golden age and the unsung genius of an innovator whose ideas continue to keep us safe on the roads today.