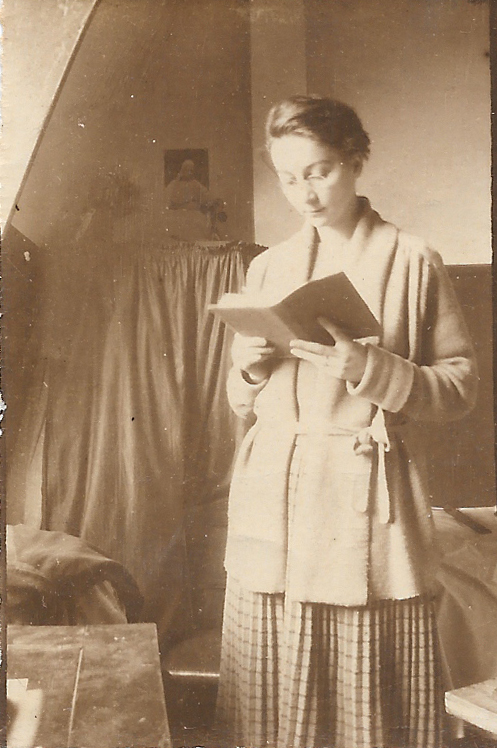

An unlikely superhero spy; a bookish art historian in a paisley print dress, posing rather meekly beside her inventory of valuable museum works. But behind the innocent smile and the matronly garb, Rose Antonia Maria Valland was a lone female agent of espionage who, during WW2, tirelessly and valiantly put her life on the line for the love of art, saving scores of looted works of art during Nazi occupation. She is the subject of a new book The Art Spy: The Extraordinary Untold Tale of WWII Resistance Hero Rose Valland by Michelle Young, who will be the special guest author for our July salon of the Paris Writers and Readers Club (July 17th). In the meantime, we caught up with Michelle during her publication week for a behind-the-scenes look at Rose Valland’s Paris, including some of her old haunts.

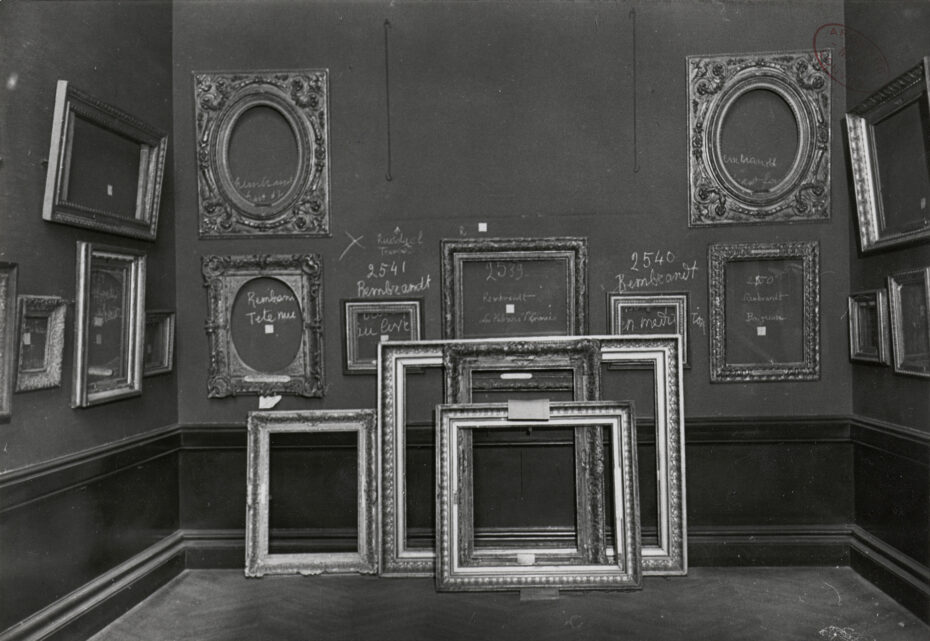

But first, for those unfamiliar – who was Rose? Her unexpected career as an art spy began during World War II, when the museums of Paris, with their invaluable art collections, fell prey to German wartime greed, with systematic raids orchestrated by Hitler’s art-looting arm. At the time, Rose Valland worked as a curator at the Jeu de Paume Museum in Paris’s Tuileries Gardens. It so happened that Hitler made this very museum the sorting for his art-looting organization, Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) and the place where much of the confiscated art and artifacts would be stored before they were expatriated to Germany.

Rose was ordered by her boss Jacques Jaujard, head of the French Musée Nationaux, to “stay at all costs at the Jeu de Paume.” At great risk, Rose spied under the nose of the Nazis for four years, witnessing the arrival of figures like Hermann Göring, who visited the museum at least twenty times for elaborate art “shopping trips.”

Valland with her unassuming appearance would make the perfect undercover agent; a mousy, bespectacled spy on a secret mission to keep tabs on looted art. Rose kept meticulous records of over 20 000 pieces of art, artifacts, silverware, jewellery and other valuables that were squirrelled away to the halfway house at the Jeu de Paume museum (a former tennis court for the royal court).

A handy and rather well-kept secret was that she also happened to understand the German language. Rose’s lifelong partner, Joyce Heer, was a British citizen whose father was German. She grew up in England and Germany and came to Paris in 1928 to study at the Collège Feminin de Bouffémont, a finishing school where Rose Valland happened to be the French language teacher. As the plundering continued, she harvested intel on artworks that were taken directly to railway stations by speaking to unsuspecting German truck drivers, all the while relaying this information to the museum’s director. Throughout the war, she kept tabs on the logistics of incoming and outgoing artworks, recording where to and to whom they were being shipped in Germany, risking her life to keep the French Resistance movement informed.

“One of the most exciting aspects about writing my new book was tracking down Rose’s Paris haunts”, Michelle tells us. “It’s a city I know well — I lived in Paris in my late 20s, studied there, started dating my future French husband there, and I still spend long stretches of time in France several times a year, whether for work or family. Rose Valland first came to Paris in 1924, an era known as les années folles: the crazy years. The cafés were brimming, and nightlife buzzed. Paris was the epicenter of it all— art, cinema, dance, theater, and music. Rose was a student first at the École des Beaux Arts, then at the Sorbonne, the École des Hautes Etudes, and the École du Louvre. An exuberant raucousness pervaded the streets day and night. All the notable artists, like Henri Matisse and the cubists—Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso, and Juan Gris— were living or working in the city.”

Fortunately for Rose, who preferred the company of women, social norms were changing, too, Michelle points out, who went to great lengths to meticulously research all aspects of her heroine’s double life for the book. “In the cinema and in fashion, women like Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich wore pantsuits and cut their hair short. Rose followed suit, pushing the boundaries even further by dressing à la garçonne, with a gender-bending boy cut and a chic blue suit she particularly loved.Paris, the lesbian capital of Europe in the Roaring Twenties, would have been a place for Rose to start exploring her emerging sexual orientation. She was in an open-minded city far from the conservative religious milieu she grew up in in Saint-Etienne-de-Saint-Geoirs, southeast of Lyon. Gay women from around the world, including New Yorker columnist Janet Flanner, Polish painter Tamara de Lempicka, and British poet Renée Vivien, fled to Paris in search of sexual freedom. Bars like Le Monocle, Le Hanneton, and La Souris — hidden in plain sight in Montmartre — and the salons of Gertrude Stein and her lover Alice B. Toklas, as well as those of American heiress Natalie Clifford Barney, were a haven for women from all walks of the sexuality spectrum. It’s unknown if Rose frequented these places but she undoubtedly knew of their existence and certainly dressed the part”.

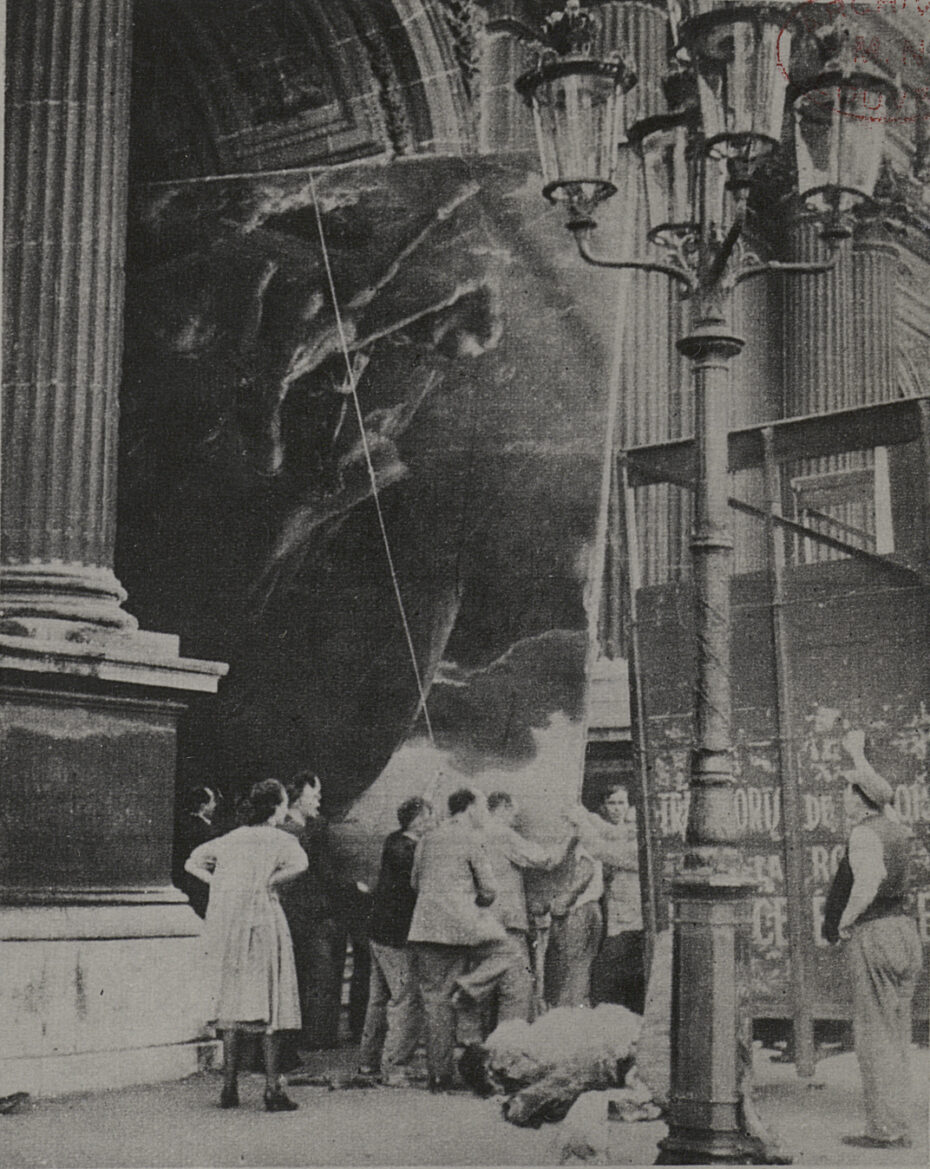

Back at the museum, extraordinary intel came on August, 1st, 1944 (and just prior to the Liberation of Paris on August 25th, 1944): the head of the ERR in France, Heinrich Baron von Behr, was plotting a major exodus of artworks, including modern works of art which the Nazis hadn’t been interested in up to that point. To her horror, Valland discovered that 148 crates filled with 967 paintings, including works by Gauguin, Modigliani, Picasso, Toulouse-Lautrec, Braque, Cézanne, Degas, Utrillo and Dufy were being loaded into five wagons at the train station at Aubervilliers, Paris. Valland sent word of the shipment to Jaujard, who in turn forwarded it on to the French Resistance.

As luck would have it, the French railway workers were on strike when the train was finally ready to depart, on August 10th, 1944. The overloaded train with artworks eventually departed but suffered a mechanical breakdown, and by the time the Germans had fixed the problem, the French Resistance managed to derail two trains, blocking the tracks and leaving the art cargo in limbo. This enabled the Second Armoured Division of the French Army to secure the train. Under a Lt. Alexandre Rosenberg, they despatched 36 crates to the Louvre for safekeeping, but it took a further nerve-wrecking two months before the remainder of the crates were moved to safe storage.

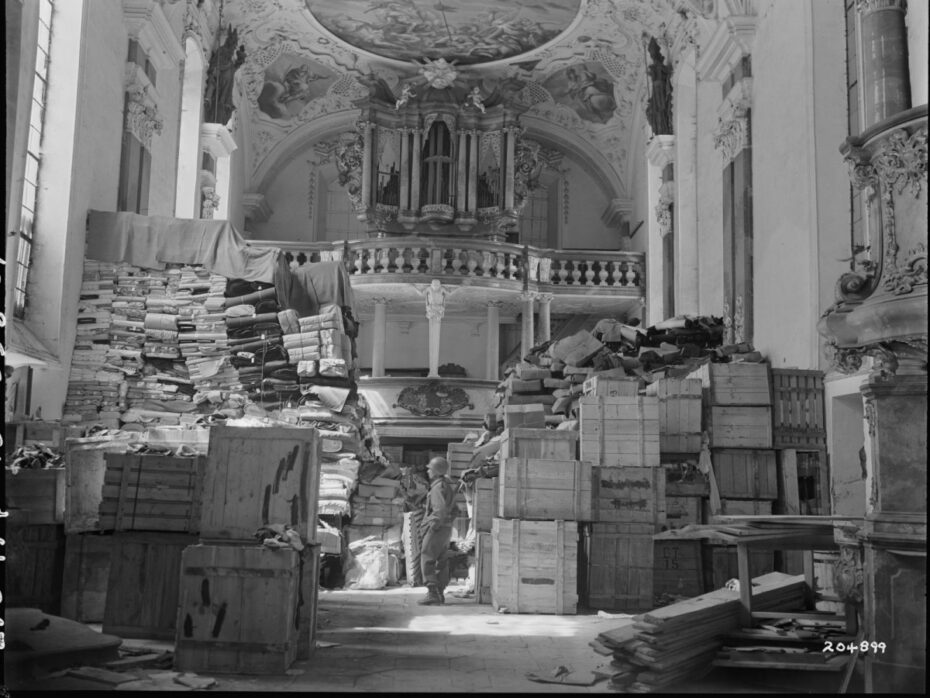

Once the Allied Forces had liberated Paris, Rose Valland was arrested as a suspected Nazi collaborator because she had been working at the headquarters of the ERR, but was soon released. She was understandably reluctant to share her records with anyone but Jaujard, however did eventually trust American Captain James Rorimer in charge of the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives initiative enough to disclose her secret information. This enabled the discovery of numerous secret locations where art was stowed away, for example, Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria, where more than 20,000 prominent pieces of art were unearthed. Not only did Valland personally assist in returning artworks to Jeu de Paume, but she also helped reunite private artworks with their respective owners.

Rose Valland was made lieutenant, then a captain in the French Army at her request in 1945, to facilitate her efforts in locating and returning stolen artworks. She served in Germany for 8 years, where she was the French government’s direct liaison. She was also a witness at the Nuremberg trials in 1945, where she challenged Goering on the artworks he personally stole from France. She was put in charge of the French Oversight Board in 1946, from where she recovered priceless French art, tapestries, sculptures, coins and other artefacts. With her help 60,000 pieces of art were returned to France before 1950.

To this day, the initials MNR (Musées Nationaux Récupérations) are seen on around 2,000 works of art in French museums that vanished during the second World War, and whose legitimate owners have not been identified, as they themselves may also have ‘disappeared’. Look out for the letters “MNR” on the placards beside paintings.

Today, there are several places in Paris to pay your respects to Rose, a true French heroine.

There is the plaque on her apartment building at 4 rue Navarre, but also a more recently dedicated plaza next to the Jeu de Paume. There is also a Passage Rose Valland in the 17th arrondissement. The Jeu de Paume is still a museum (they have a robust section of Rose Valland books for adults and children, in their gift shop) but now dedicated to modern photography, and across the street at 2, rue Saint-Floretin is the hôtel particulier that belonged to Edouard de Rothschild, which was heavily looted by the Nazis in Rose’s museum during WWII.

The Art Spy: The Extraordinary Untold Tale of WWII Resistance Hero Rose Valland can be

purchased at all good bookstores, including Messy Nessy’s Cabinet! Michelle Young will be speaking at the Paris Writers and Readers Club at the Cabinet on July 17.