It was an ambitious, otherwordly idea, dreamt up by American military physician, Dr. Bond, deemed too risky and ultimately rejected by the US Navy. Bond then turned to French diving/ filmmaking pioneer Jacques Cousteau and his ‘Calypso’ diving team, who accepted the challenge, never before attempted by man, to build an underwater colony where divers could live under the sea.

Sounds like the stuff movies are made of? You might recall a little indie film made a few years back by Wes Anderson called The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, which would have come across as largely fictional. Actor Bill Murray’s character, Steve Zissou is in fact both a parody of and homage to the underwater adventurist, Jacques Cousteau (who also happens to be credited with the invention of scuba diving). Cousteau’s ship was the Calypso. Zissou’s ship in the film is called the Belafonte; Harry Belafonte became famous singing commercialised calypso songs. So now that we’ve established where that whole hipsters-in-red-beanies trend actually came from, let’s see what the real life aquatic with Steve Zissou was like…

Conshelf I:

While Hollywood in the 1960s was fantasizing about it with their science fiction films, Jacques Cousteau’s adventure was already underway. The project was known as Conshelf, with a goal to send up to ten aquanauts to live in the sea for one month inside a habitat filled with oxygen and helium.

The first habitat, Conshelf I, made history in 1961 when two divers of Cousteau’s Calypso team lived in a small underwater habitat the size of a shipping container at 37 feet deep for one week. The drum-shaped structure had a hatch for the divers to enter and exit their underwater home to carry out research on the seabed.

Conshelf II:

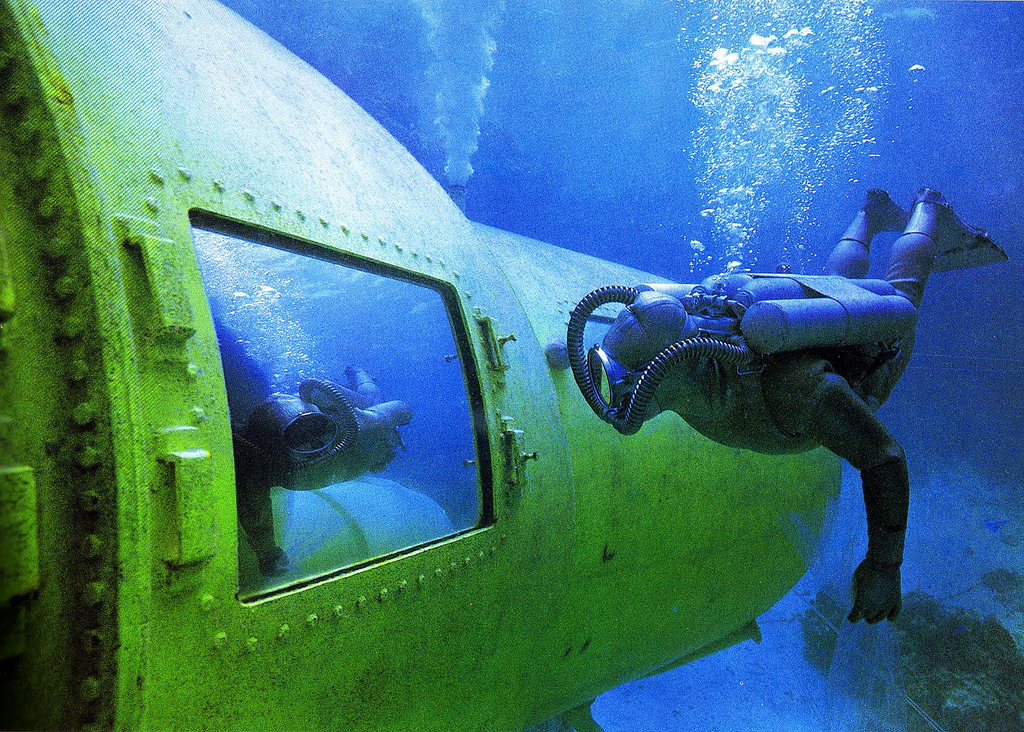

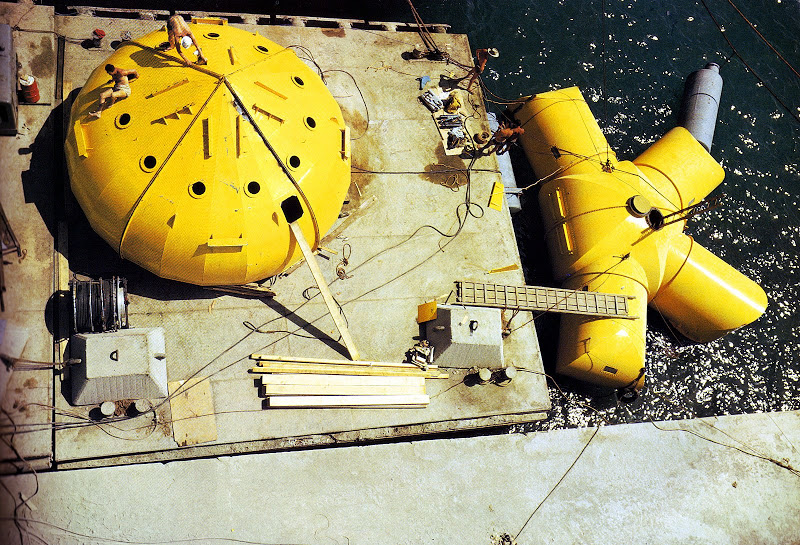

Only a year later, Conshelf II was born in the Red Sea off the coast of Sudan. This time, six divers would live for month underwater, without sunlight in a starfish-shaped house. A smaller and deeper cabin housed two oceanauts for a week at 82 feet.

Conshelf II then:

Conshelf II now:

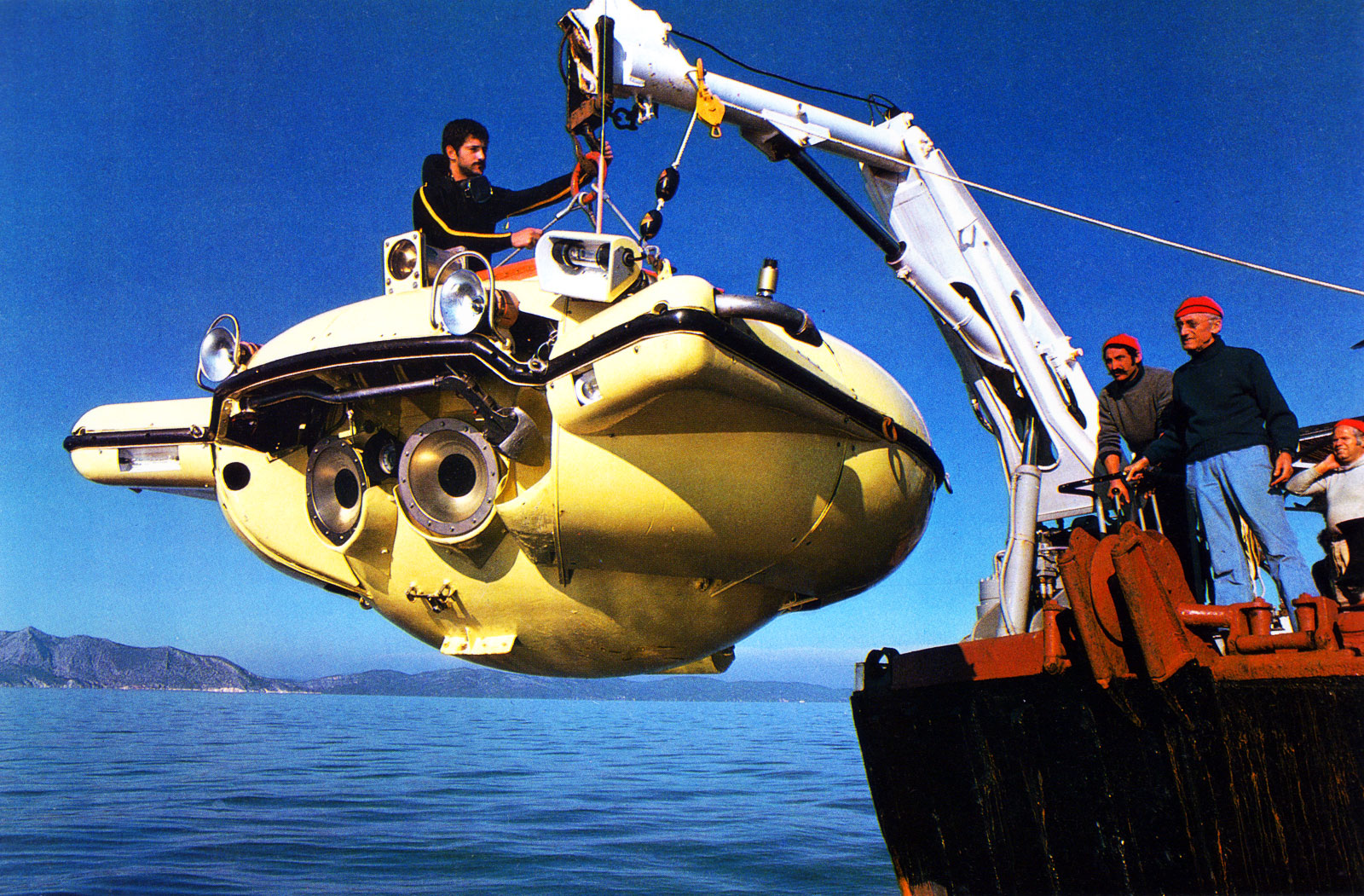

The divers extensively studied shark behaviour during Conshelf II, venturing out into cages as deep as 170 feet. Cousteau also made cinematic history when his team journeyed up to 1,000 feet deep in his yellow submarine, depths no camera had ever reached, to capture images of microscopic plankton.

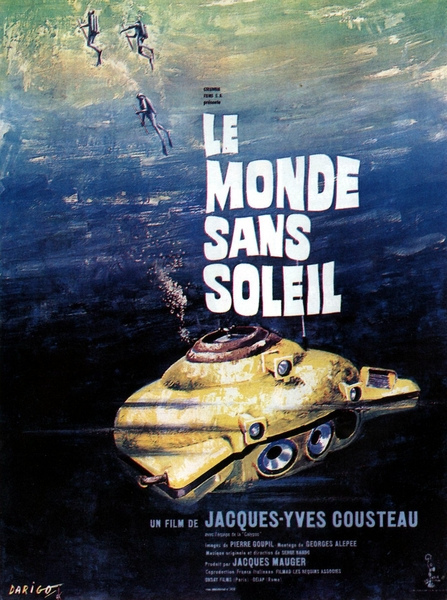

The entire expedition is documented in Jacques Cousteau’s 1964 documentary film World Without Sun, which won the Oscar that year for best documentary.

Conshelf III:

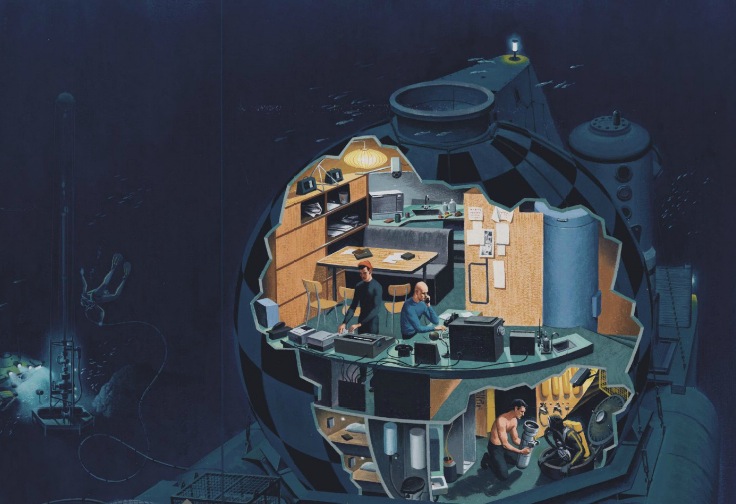

Conshelf III, the most ambitious of all attempts, kicked off in 1965, and six divers lived for three weeks in the habitat at 336 ft deep near the Cap Ferrat lighthouse, between Nice and Monaco.

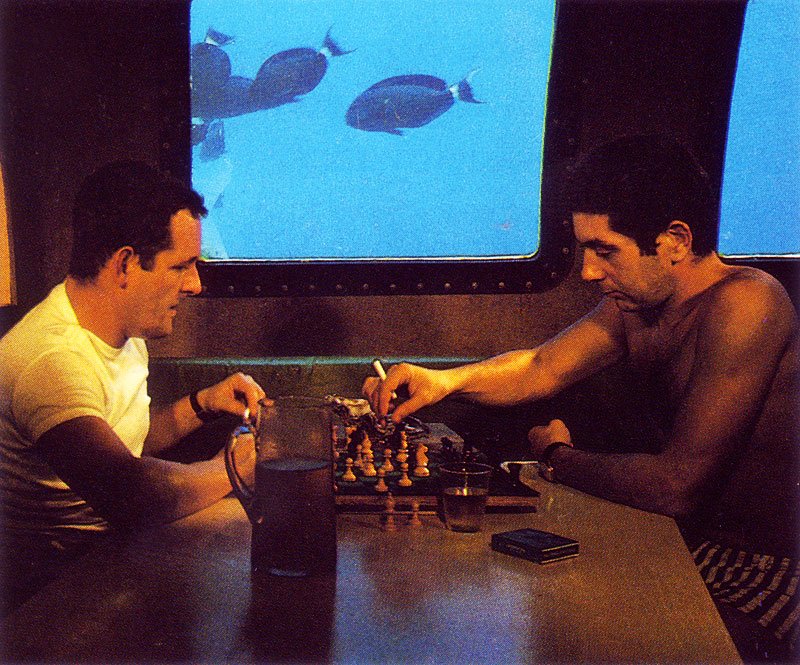

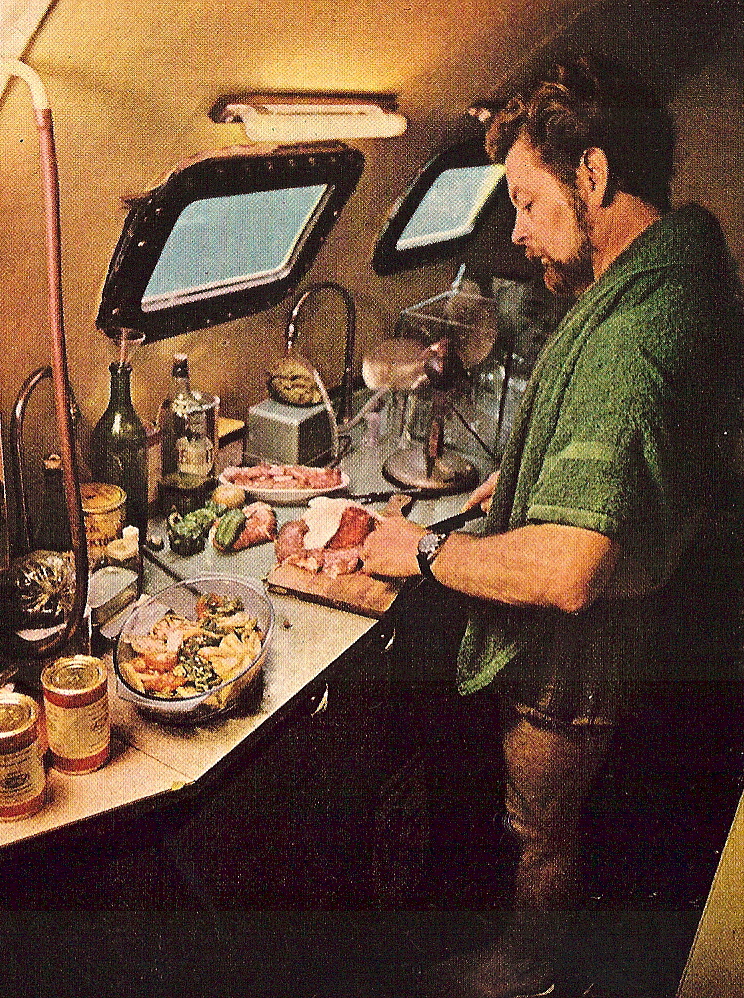

In this experiment, the divers, including Cousteau’s son Philippe, were totally self-sufficient and a replica oil rig was set up underwater where they were required to perform several industrial tasks.

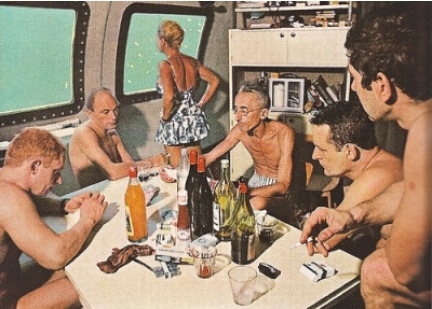

Inside the Conshelf III, image credit: Davis Meltzer

The French petrochemical industry had been funding Cousteau’s adventures but were sadly less concerned with studying the seabed and more interested in exploiting it. When it was found in later years that industrial tasks underwater could be done just as well if not more efficiently by robots than human divers, it was to be the end of Conshelf. Cousteau famously publicised his regret in working with the petroleum industry on his projects. He had hoped that his manned underwater habitats might serve as base stations for future exploration of the sea, but alas, his dream of installing his colonies in oceans across the globe was never achieved.

So, now we know a little bit more about the real-life Zissou, how about we make tonight’s homework to watch/ re-watch Wes Anderson’s The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou: