Not many can boast to have made it to the top of the Nazis’ “Most Wanted” list in Paris during World War II, and still fewer Allied radio operatives stayed at the top of that list for longer than a few weeks. Noor Inayat Khan exceeded these expectations, working fervently to bring freedom to Europe with the hope that she could engender better relations between her father’s home country of India and Great Britain– the country she called home and for which she gave her life in Dachau at just 30 years of age.

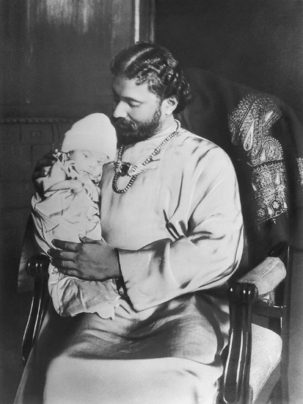

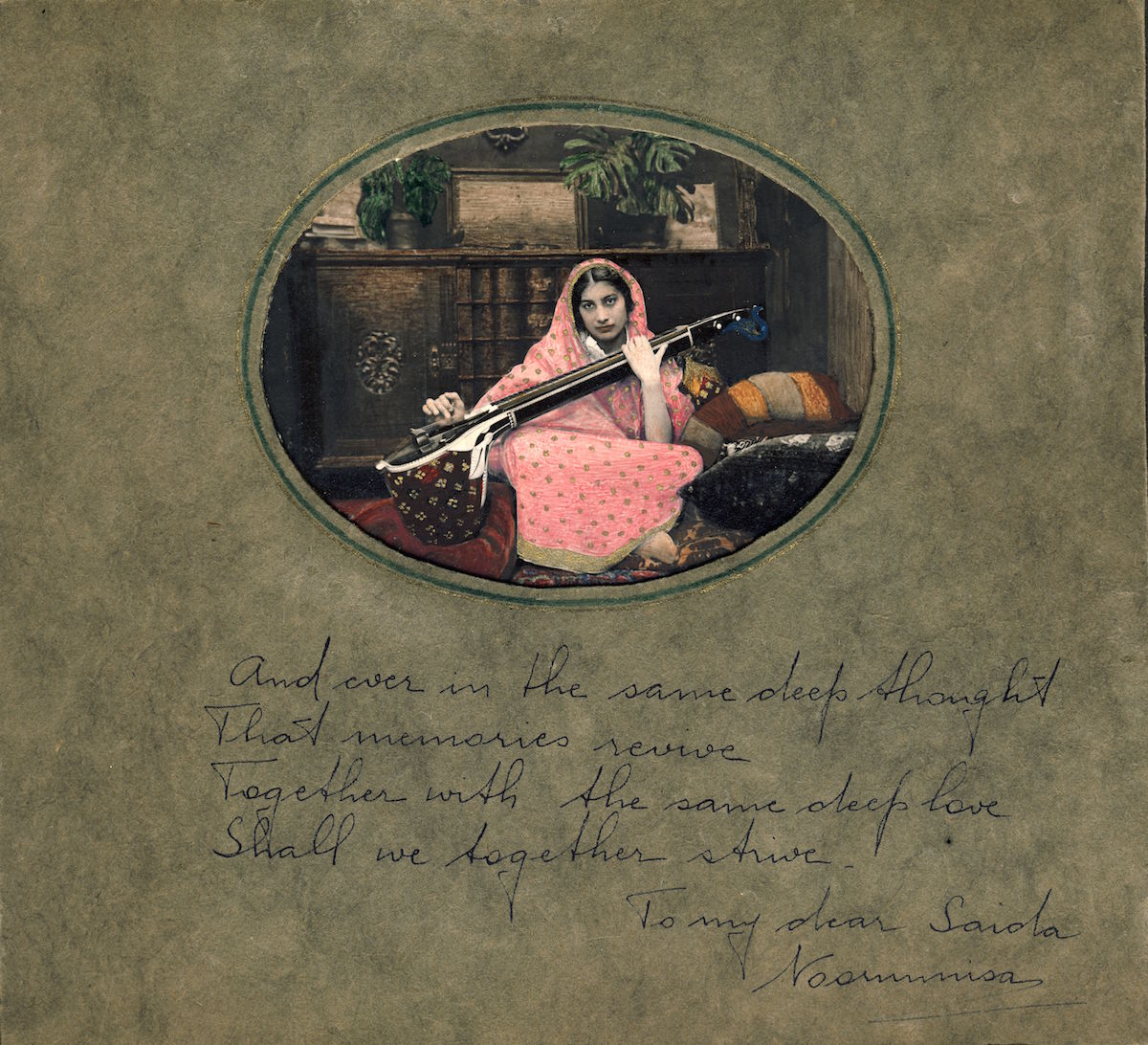

Born in Moscow to an Indian father and an American mother, Khan lived all over Europe in her short life. Her father was a globe-trekking musician, Sufist teacher, and a descendant of Tipu Sultan, an Indian Muslim noble who famously stood up against British colonialism in the 18th century.

During her father’s journeys to all corners of the world, he met Khan’s mother, whose guardian and half-brother, Pierre Bernard, was a renowned American yogi.

After Khan’s birth and shortly before the Great War, her family moved to London, where they stayed until settling in Suresnes, a hilltop suburb of Paris, in 1920. Described as a quiet and thoughtful individual, Khan excelled in nearly everything she put her hand to. At only 25 years old, she published a children’s book inspired by Buddhist tales.

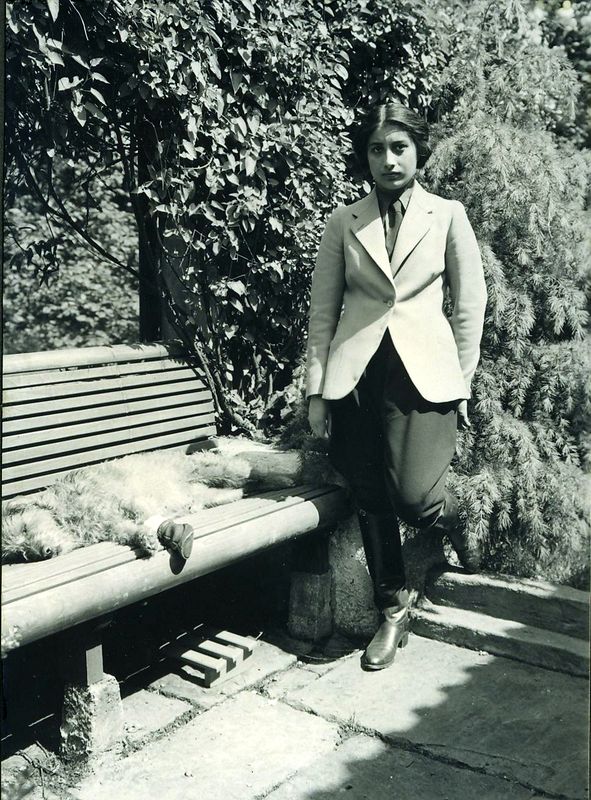

Khan studied child psychology at La Sorbonne and, following in her father’s footsteps, she studied music at the Paris Conservatory under the tutelage of the famous Nadia Boulanger, who taught many 20th-century greats, including Aaron Copland and Quincy Jones.

When the Nazis invaded France, Khan and her family fled back to England, where she joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF). Getting involved with the war was at odds with her pacifist Sufi beliefs. Khan put these aside for several reasons, not least of all to inspire a change between Britain and India, once telling a family friend: “I wish some Indians would win high military distinction in this war. If one or two could do something in the Allied service which was very brave and which everybody admired it would help to make a bridge between the English people and the Indians.”

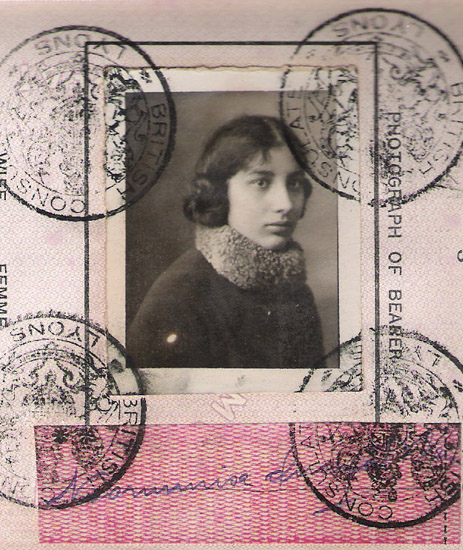

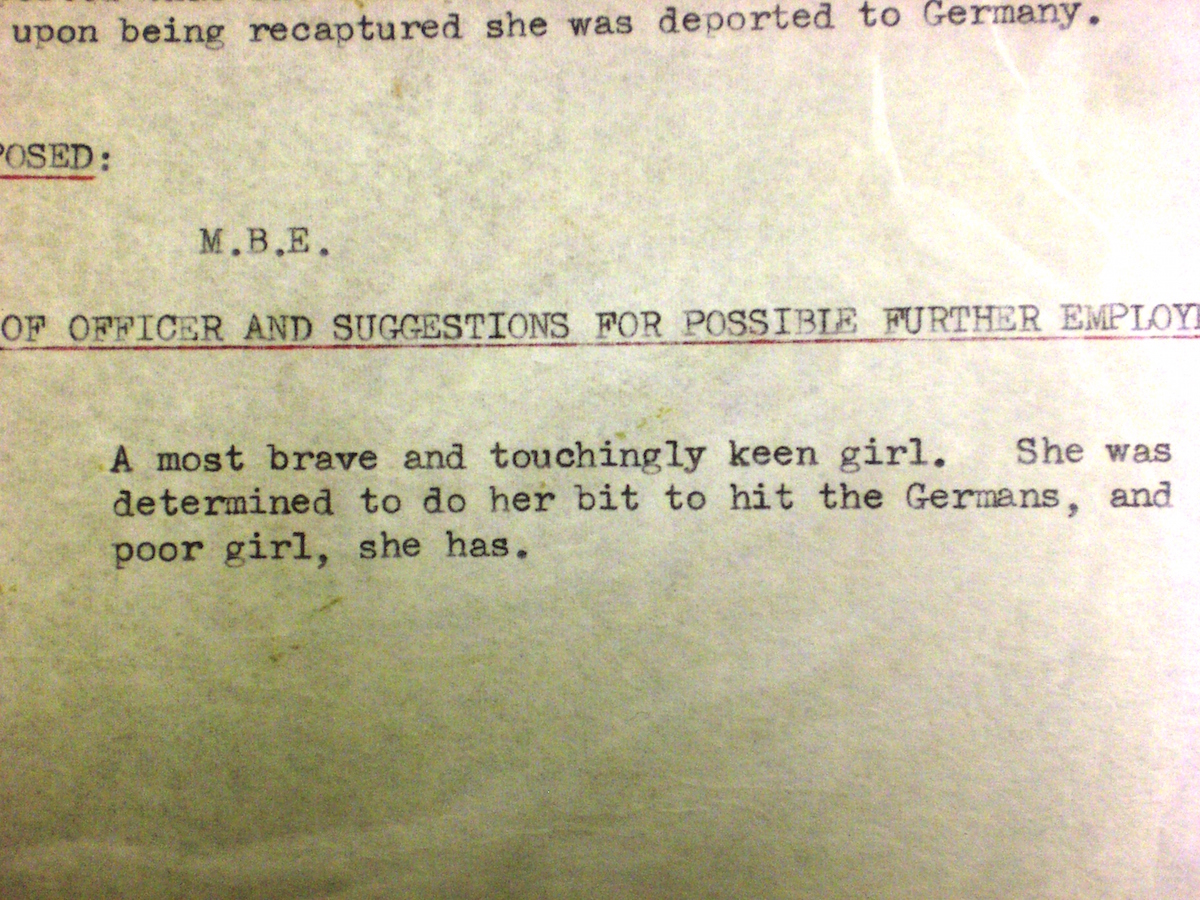

Not destined to remain with the WAAF, Khan was recruited by the Special Operations Executive (SOE), given her multilingual background and her skills in radio operation. But with a reputation for being “shy” and “sensitive,” not all of her superiors felt sure she would succeed. Nevertheless, they sent her to Paris in June of 1943 as the operation’s first female operative assigned to Nazi-occupied France.

Undercover as a nurse named “Jeanne-Marie Regnier,” she worked with several other agents as a unit. Just over one month following Khan’s arrival in France, all of her fellow unit members had been arrested by the Nazis.

The surprise was not that the others were arrested, but that Khan was not; most SOE radio operatives were not expected to survive more than six weeks in the field. Khan eluded capture for four months, essentially leading the most critical radio operation in Paris by herself after month two under the code name, “Madelaine.”

As the Nazis’ most-wanted British agent in the city, she had to move to a new site every night and could not transmit for more than twenty minutes at a time. On October 13th, 1943, the Nazi Sicherheitsdienst (SD) arrested Khan after someone betrayed her location.

Some hypothesise that SOE officer Henri Déricourt was to blame, either because he was a double-agent or because he acted for MI6 as a faux double-agent in order to gain the Germans’ trust and secure further intelligence. Others claim that Renée Garry, the organiser of Khan’s radio network, fell out with Khan because Garry’s lover, Franco-Mauritian SOE agent France Antelme, left her for Khan. The Nazis supposedly paid Garry 100,000 Francs for information on Khan’s whereabouts.

During the Nazis’ interrogation of her, the “sensitive” Khan gained such a reputation of ferocity that the German officers reportedly found her terrifying. Head of the Nazi’s Parisian Security Services, Josef Kieffer, testified after the war that Khan did not let slip a single piece of information about the SOE radio operation. Kieffer cried when SOE France commander’s right-hand-woman, Vera Atkins, testified of Khan’s death during his war crimes trial in 1946, to which Atkins scornfully replied, “…if one of us is going to cry it is going to be me. You will please stop this comedy.”

Unfortunately, Khan left notebooks behind in which she had recorded every message she sent– a serious security risk. This error possibly stemmed from the brevity of her training (due to an extremely high need for SOE agents because most were captured or died within six weeks), and a misunderstanding as to what the SOE office meant by the requirement of filing her records. Using her recognisable style, the Nazis were able to transmit fake messages long after her capture which the British accepted as real. Sonya Olschanezky, a French agent attached to the SOE, sent a message to British headquarters that Khan was captured and to no longer accept transmissions from “Madelaine,” but not recognising Olschanezky’s name, headquarters disregarded her warning. This grievous mistake led to Olschanezky’s death in 1944.

Khan escaped from the German security service in November 1943, and upon recapture was told to sign a statement that she would not attempt escape again. She refused, so the Nazis sent her to Karlsruhe prison in Germany and then to Pforzheim, as part of the “Night and Fog” initiative, a plan to clandestinely wipe out any individuals threatening the Nazi regime. Considered a dangerous prisoner, she was shackled constantly. Within three days of her final transfer to Dachau concentration camp in September 1944, nearly a year after her capture, she and three other female SOE agents were executed and then cremated. Khan’s last word was, “Liberté.”

Noor Inayat Khan, Britain’s first Muslim war heroine, was posthumously awarded both the British George Cross and the French Croix de Guerre with a silver star; two of the highest military honours either country could offer. But her remarkable life often goes unremembered. Three years after her death, India gained its independence–something she so greatly desired that she said so outright in her initial SOE interview at the risk of not getting the job and, worse, at the risk of being labeled treasonous. Khan gave all in spite of adversity, to the benefit of those she most desperately endeavoured to save.