Once upon a time, in a pre-smartphone world, people had to make their own entertainment. And so enters the salon, an Italian-influenced tradition of gathering of artists, writers, musicians, dancers, philosophers and intelligencia that flourished during a period known as the ‘age of conversation’. Dating back to the 17th century, guests would assemble in the fabulous private residence of an inspiring host to share their latest ideas – and naturally, a few glasses of wine. Historically, European salons, notably in Paris, were among the few places where men and women of various social hierarchies could mingle and, most importantly, where women were in charge, carrying crucial and powerful roles as regulators. One of the earliest recorded renowned salon hosts, or salonièrres, was Catherine de Vivonne, Marquise of Rambouillet, who ran her Parisian salon near the Louvre from 1607 until her death in 1665. Such gatherings allowed women not only to engage in academic discussions but actually choose and influence the subjects of conversation, thus the subjects explored by the artists, philosophers and thinkers of the day. As a bi-product, salons played a vital role in the integration of some of history’s most iconic women, such as Colette and Amantine Lucile Dupin (aka George Sand), into wider society.

The private and ‘behind closed doors’ nature of the salon has resulted in a somewhat hazy and conflicted knowledge of exactly what went on inside them, who was there and how they were conducted. Frequently depicted as debaucherous and leisurely affairs, or snobbish ‘schools of civilité’, it’s been argued by scholar Dena Goodman in The Republic of Letters, that on the contrary, the salon has been overlooked as the “the very heart of the philosophic community” and “integral to the process of the Enlightenment itself”.

While they were notably hosted by “women of society”, in contrast to the royal courts of the old regime, the salon left social hierarchy at the door. Mingling between the sexes, ranks and religious backgrounds was encouraged, helping break down social barriers and allowing in prolific but lower middle class thinkers such as Voltaire, Marcel Proust and even Karl Marx, to influence the powerful elite.

At the centre of it all, the salonièrre selected her guests and decided on the subjects of their meetings, ranging from literary, social or political topics. As mediator of the discussion, she was able to give her own ideas and criticisms, even read her own works and have a front and centre seat amongst the most important intellectuals of the day. In essence, it could be argued that the salon was a woman’s own private university.

Each salonièrre typically had her own alloted day to hold a gathering once a week, which was announced in public journals. Attendees would drop off their visit cards to the maître d’hôtel, and were accepted at the lady’s discretion, usually thanks to the recommendation of a previous guest or through prior introduction.

Today, many of the most iconic Parisian salons continue to be used as private residences. One such address is 27 rue de Fleurus. The only nod to its cultural significance is a small plaque outside that reads: “Gertrude Stein, 1874 – 1946, American Writer. Lived here with her brother, Léo Stein, and then with Alice B. Toklas. She received numerous artists and writers between 1903 and 1938”.

Anyone who has read Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast or seen Midnight in Paris will know that this is something of an understatement. Gertrude Stein’s Saturday evening salons were a melting pot for the likes of Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, to name but a few. Here, artists of all disciplines would drop by to seek creative advice from Stein and whomever else may have been passing through at the same time. It was here that Paris’ “Lost Generation” was christened and nurtured by the host herself.

Her apartment, dubbed “the first museum of modern art”, filled with Picasso’s, Cezanne’s and the like, was never preserved or opened as a museum after her death, sold off, along with her collection to various museums and collectors. In 1992 a replica of Stein’s intimate Parisian apartment was reconstructed in New York and christened the Salon des Fleurus after her address at 27 Rue de Fleurus. It closed after 22 years in 2013 to go “on tour”, reportedly to find a new home in Paris, but was never reopened.

Equally worth mentioning is Natalie Clifford Barney, a lesser-known Gertrude Stein and forgotten LGBT queen of Paris, who curated a literary salon with just as much clout for over 60 years at her secret Masonic temple. As Hemingway put it, “There are so many salons in Paris tended to by expats, but Ms. Barney’s seems to be the only one with an actual temple.”

These days, if you linger by the door of 20-22 rue Jacob in the backstreets of Saint Germain, where Barney held court for so many decades, you may be able to sneak inside to get a peak of the legendary space with a link to some of the world’s most remarkable (and conspiracy-prone) sites. You can dive down that rabbit hole here.

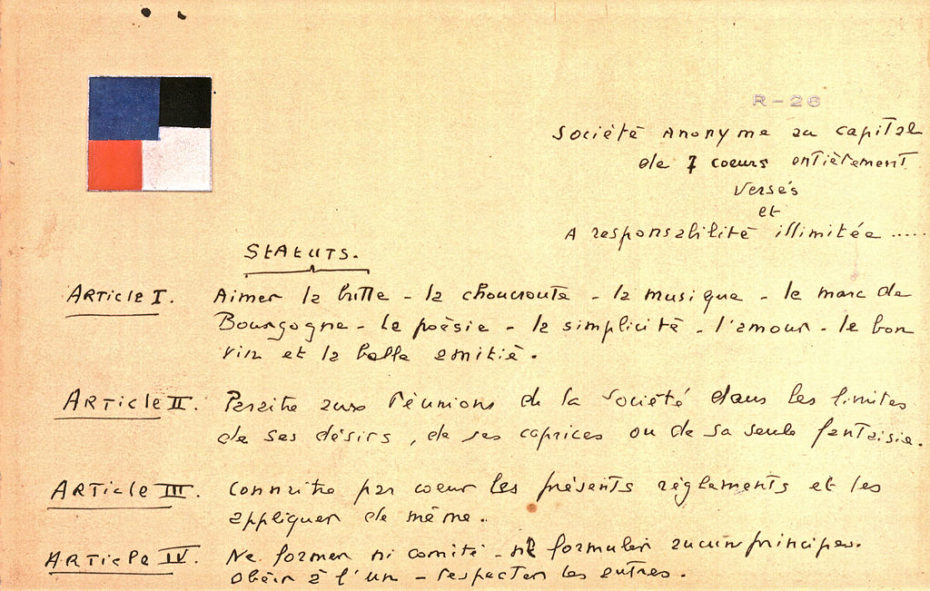

Likewise, at the R-26 salon, which took place in a building that no longer exists in Montmartre, Robert and Madeline Perrier (no relation to the fizzy beverage brand), welcomed everyone who was anyone to their home throughout the 20th century. Over the following decades, regulars included people from the world of music – Josephine Baker, Django Reinhardt – architecture – Le Corbusier – and the avant-garde art scene – Yves Klein and Georges Vantongerloo, who designed the club’s Cubist logo on the night of its inauguration. The increasingly frequent attendees officially dubbed their salon “R-26”, in reference to their host, Robert, and the address at what was then 26 Rue Norvins.

After the death of Robert Perrier in 1987, Marie-Jacques continued to run the salon, opening it up as an artist residence to more than a hundred international creatives and students into the early millennium.

Of the myriad humble – and not-so humble – homes that once hosted the luminaries of their time, several remain open as museums, as do many of the homes of those who would attend them. Today, each one is a portal into the social circles, salons and ateliers of times gone by that continue to draw people to Paris to this day.

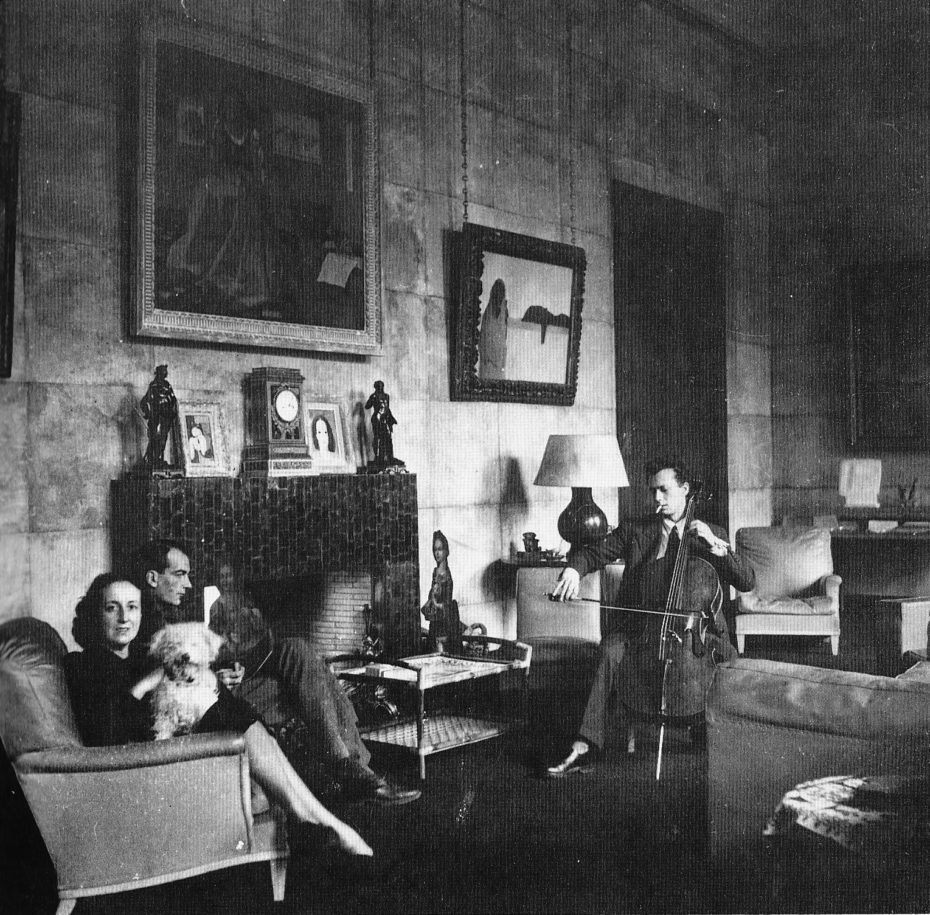

Musée Baccarat

The concept of the Parisian salon continued to exist in society more or less until the 1950s, continuing the tradition of women hosting and mixing intellectuals and political thinkers. Among the last salons in Paris were those of Marie-Laure de Noailles, an artist and great grand-daughter of great-grandfathers was the Marquis de Sade, who entertained the likes of Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Jean Cocteau, Man Ray, Igor Markevitch (with whom she had an affair), Salvador Dalí in her living room at the fabled hôtel particulier at 11 Place des États-Unis in Paris.

Today, the interiors have been renovated by designer Philippe Starck and house the private museum and headquarters of the iconic crystal company, Baccarat.

The former private mansion of Marie-Laure de Noailles is open daily except Sundays, Tuesdays, and holidays to admire the mansion and a selection of Baccarat’s heritage collections. More interestingly, you can also book a table in the crystal room and dine where the last Parisian salons took place in the gorgeous setting of this Michelin star restaurant (11 Place des États-Unis, 16ème; 01 40 22 11 10; Tuesdays to Saturday, lunch & dinner; Cristalroom.com).

Musée Jean Jacques Henner

To imagine the ambiance of a artistic Parisian salon of the Belle Epoque, look no further than this former home and studio of the prolific painter in the 17th arrondissement. Try your hand at model sketching in a sumptuous 19th century artist’s house-turned-museum after hours. The museum frequently hosts regular drawing workshops here for professional and amateur artists alike accompanied with dance and music.

Self-proclaimed “anti-art school”, Dr. Sketchy also hosts frequently immersive experiences there, with costumed actors conjuring the atmosphere of a historical Parisian salon. Good to know: the winter garden is available to hire for parties and the maison-museum also offers artist residencies.

(43 Avenue de Villiers, 17ème; +33 1 47 63 42 73; Wed-Mon 11am-6pm; Musee-henner.fr)

Musée Jacquemart-André

It was always the intention for Edouard André and Nélie Jacquemart to open up their home to the masses – but only once they were done with it. Throughout the Belle Epoque, the creative couple dedicated their lives to collecting art from all corners of the globe, returning to Paris occasionally to drop off their sculptures from antiquity and original Rembrandts. And to throw extravagant celebrations in their opulent mansion, of course.

Upon the death of Nélie in 1912, who had been a painter herself, the estate and its vast art collection spanning practically every epoch was passed on to the Institut de France. Ever since 1913, the extravagant doors of Musée Jacquemart-André have been open to the public, with displays curated in accordance with instructions left by Nélie herself.

While some spaces have taken on a more traditional gallery aesthetic, the majority of the mansion’s rooms remain intact, just as they were over a hundred years ago. Meaning you are free to roam through the bedrooms and libraries as though you were to the manner born, taking for granted the Botticellis hanging on the wall while you decide which of your ball gowns to wear for the gala tonight. (158 Boulevard Haussmann, 8ème; website)

Musée National Eugène Delacroix

“My apartment is decidedly charming,” wrote Eugène Delacroix of his then-new home on Place de Fürstenberg in 1857. The same can be said of the museum that it has become. Considered among the last Old Masters, the decision to commemorate his life’s work by transforming his house into a museum came not from friends or family, but his artistic admirers some 70 years after his death. The second-floor apartment where he lived has been repurposed as Musée National Eugène Delacroix.

Quite the opposite of the stereotypical artist’s garret, the museum comprises a purpose-built studio outside in the garden. It was actually the garden that attracted Delacroix to the address in the first place: a private oasis in the heart of the bustling city. Today, it is maintained following descriptions from the “Gardening memorandum for Monsieur Delacroix” – care instructions left by its previous owner when the property changed hands. Now, guests can while away sunny afternoons in the dapple of the fruit trees, discussing their next masterpiece with one another . (6 Rue de Fürstenberg, 6ème; website)

Mona Bismarck American Center for Art and Culture

Until 2019, the American Center for Art and Culture was known as the Mona Bismarck Cultural Centre. Despite the name change, the private 19th-century mansion on the banks of the Seine with a view of the Eiffel Tower continues to maintain a steady programme of events that bridge French and American culture, just as Mona Bismarck intended. In her lifetime, Kentucky-born Bismarck set the benchmark for the image of a glamorous socialite: “she was buried in a Givenchy gown and rests with her third and fourth husbands”. Painters (Salvador Dalí), photographers (Cecil Beaton) and fashion designers (Cristobal Balenciaga, Hubert de Givenchy, Christian Dior) all shared her as a muse throughout her life, which was – needless to say – fabulous thorough and through.

In 1956, she moved to Paris with her third husband and a vast inherited fortune. . They purchased a house on Avenue de New York, which became the setting of countless creative gatherings. Today, it continues to welcome guests for all manner of intimate artist talks, immersive art events and the occasional jazz concert. All in the extravagant interiors of the original It-girl’s former home, which still houses some of her personal art collection – of which she is the main subject, of course. (34 Avenue de New York, 16ème; website)

Musée Victor Hugo

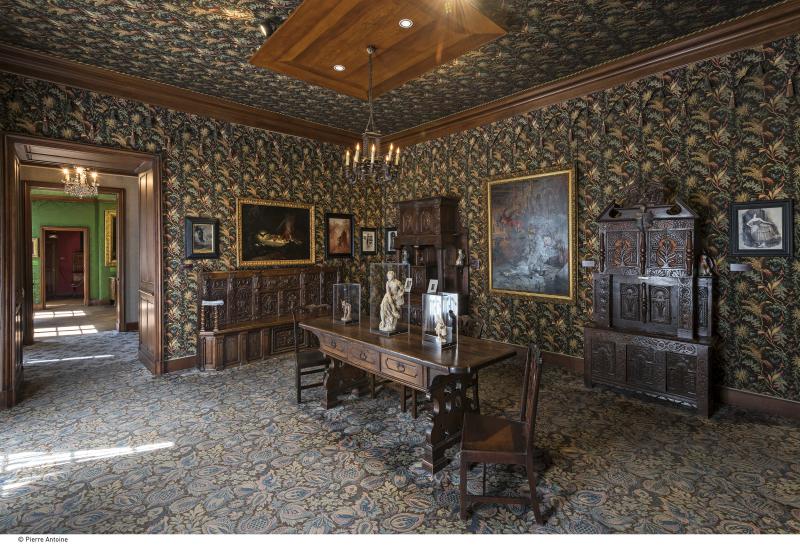

Tucked away in the corner of the regal Place des Vosges is a house museum of equal splendour: Musée Victor Hugo. The writer lived here with his family for 16 years in the 19th century, when he doubtlessly discussed his latest tomes over the dinner table. Today, the rooms have been reconstructed to replicate his opulent taste for interior design, taking cues and using an assortment of items of furniture from various places he lived throughout his life – in particular, his extravagant Hauteville House in Guernsey.

Back in Paris, no wall is left unpapered, no floor left uncarpeted. The finest example of this penchant for pattern is the psychedelic dining room, with kaleidoscopic prints from floor-to-actual-ceiling, paired with Gothic furniture. Other areas of the apartment demonstrate not just Hugo’s taste for décor, but his artistic flair, too: panels featured in The Chinese Lounge were designed by the writer himself. His ingenuity can even be found in the bedroom, where his pioneering standing desk sits – as well as the bed he actually died in, in 1885. The museum will be closed for renovations until spring 2020, when it will re-open with (among other things) a tea room, so be sure to arrive in your finest silk dressing gown and monogrammed slippers to truly feel at home. Mark your calendars. (6 Place des Vosges, 75004)

Musée National Gustave Moreau

The Musée National Gustave Moreau offers a glimpse into the eclectic interior and interior life of the 19th-century Symbolist painter it is named after. It is spread over three floors, connected by a magnificent staircase – which also doubles as a great vantage point from which to examine higher-up paintings. It contains a jumble of around 25,000 works – all decadently framed – chronicling his entire career, ranging from Italian-influenced religious canvasses to fantastical works featuring more than one mythical creature – try playing “spot the unicorn” as you explore the galleries. The artist lived here from 1852 until 1898, prior to which he personally oversaw the restructuring of the building to be used as a museum after his death. 14 rue de La Rochefoucauld, 9ème; website)

Musée de la Vie Romantique

Back up in Montmartre, the Musée de la Vie Romantique is dedicated to the writing of those who once exchanged ideas in its charming interior. Most notably among them is George Sand, the trailblazing, gender-bending 19th-century writer, considered one of the most prominent European Romantic figures of her time. She used to attend with fellow neighbour with Frédéric Chopin and met regularly with the likes of Eugène Delacroix and Gioacchino Rossini. Later in the century, Charles Dickens was a frequent guest. One of the more bizarre, though still aptly delicate features of the museum is the selection of plaster casts by sculptor Auguste Clésinger on display. Among them are Sand’s right arm and Chopin’s left hand. (16 rue Chaptal, 9ème; website).

The Literary Cafés & Bookshops

If you’re wondering what might have replaced the Parisian salon as we know it, after fading from social practice in the 1950s, one could argue that it simply shifted into Parisian café society and the various literary strongholds of the Left Bank.

Even though the likes of Gertrude Stein’s salon is no more (now a private residence), the true spirit of her salon still lives on in places like the Shakespeare and Company bookshop, which continues to offer sanctuary among the bookshelves to passing writers and artists – in exchange for some shelf stacking and writing a page-long autobiography. These “Tumbleweeds” are also required to read a book a day, a tradition instated by the shop’s founder, George Whitman. No wonder the essay section is so well-stocked!

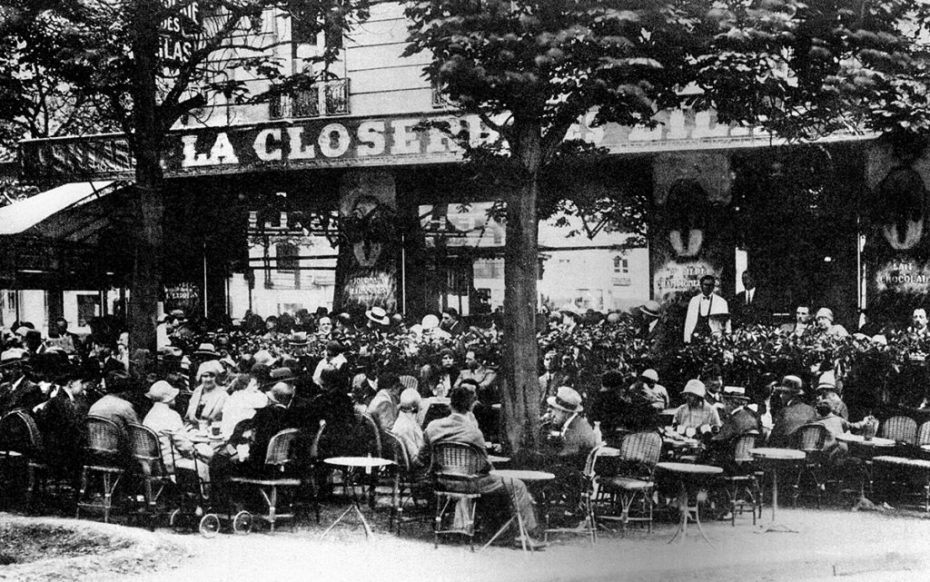

And you can still follow in the footsteps of Hemingway et al to spots like La Closerie Des Lilas – a nearby brasserie that was so popular with the creative crew it was practically as popular as Stein’s place, albeit with draught beer on tap. Every year, the restaurant hosts a prestigious women’s literary prize, bringing recognition to exceptionally talented women who have contributed to the arts, literature, journalism and politics.

Similarly, the iconic Café de Flore on Boulevard Saint Germain, presents an annual Prix de Flore to crown “promising” and talented authors on the horizon. As one of Simone de Beauvoir and Sartre’s most famous former haunts, the café also hosts a monthly “Café Philosophique” in English on the first Wednesday of each month, where you can relive Parisian café society and the “age of conversation” by engaging in philosophical discussions and intelligent debate, all in the spirit of the not-so-lost world of the Parisian salon.

(172 Boulevard Saint-Germain, 6ème; first floor from 6.45pm, first Wednesday of the month; +33 1 45 48 55 26; More info here)