Who dictates Time? Depends on who you ask, and in what century. Like us, you probably rely on a Western, 365 day calendar to tell you that today, it’s such and such date in 2020 AD. But if you asked a French Revolutionary, “Year 1” began in 1789. And if you asked an American Kodak employee in 1988, they’d say a year had 13 months. Which begs the question: are we…doing this right? As the hours, days, and weeks gain a strange elasticity in quarantine, we’ve decided to consult the history of the calendar to ask, why 365 days? Do we really need leap years, and time zones? Were they invented by a cult deity? Jeff Bezos? The truth is somewhere between the two…

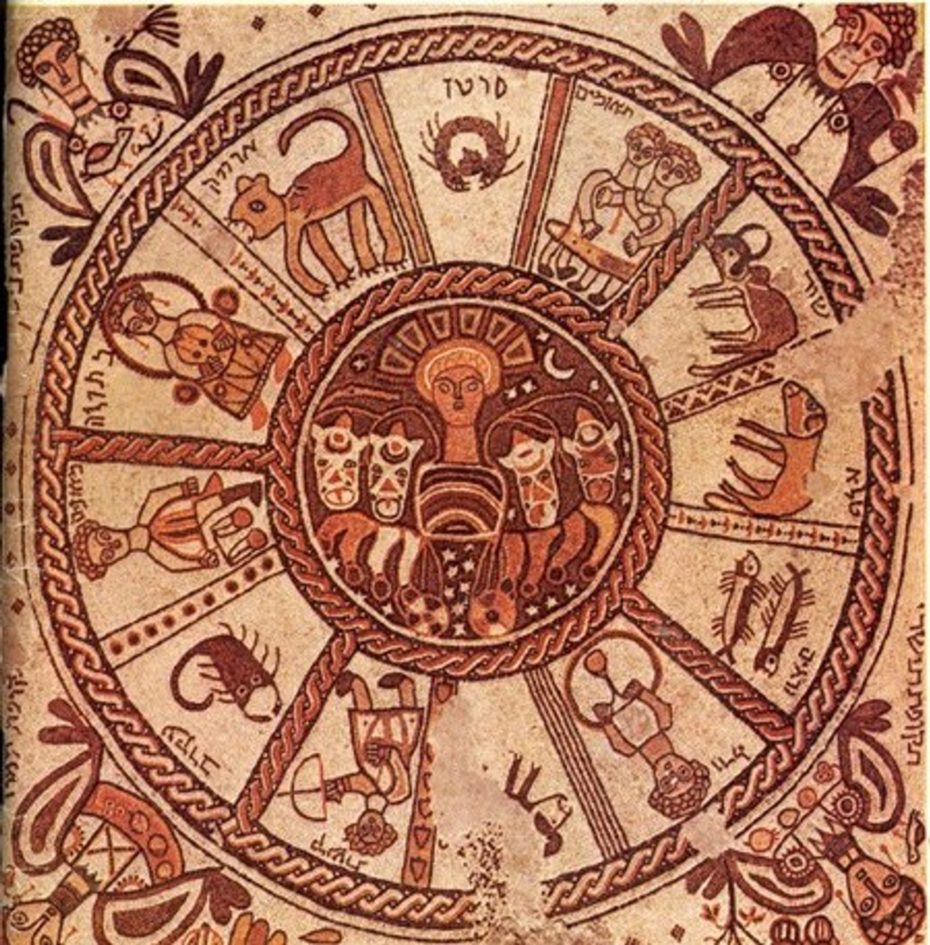

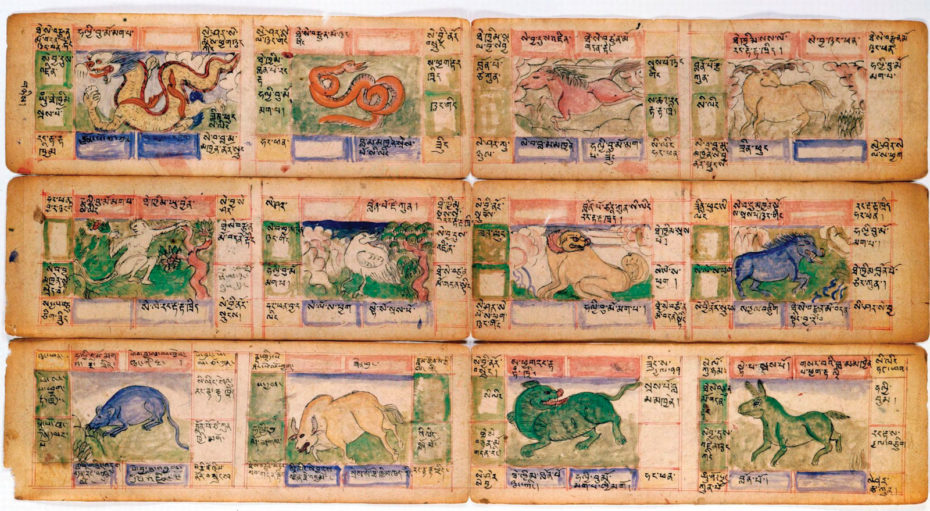

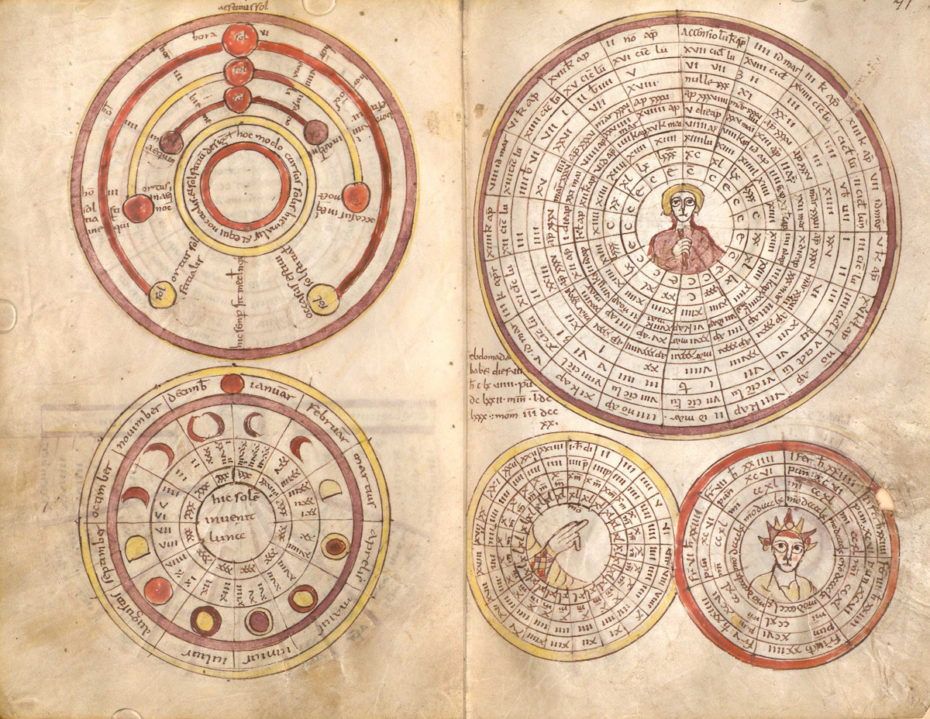

To make a long story short: the cycles of the sun and moon were how humans first told time. Still do. Only, now, the West follows a strictly solar calendar (i.e. it takes 365 days for the Earth to go around the Sun) known as the “Gregorian” calendar. But many ancient cultures actually followed a solar and lunar calendar to some degree…

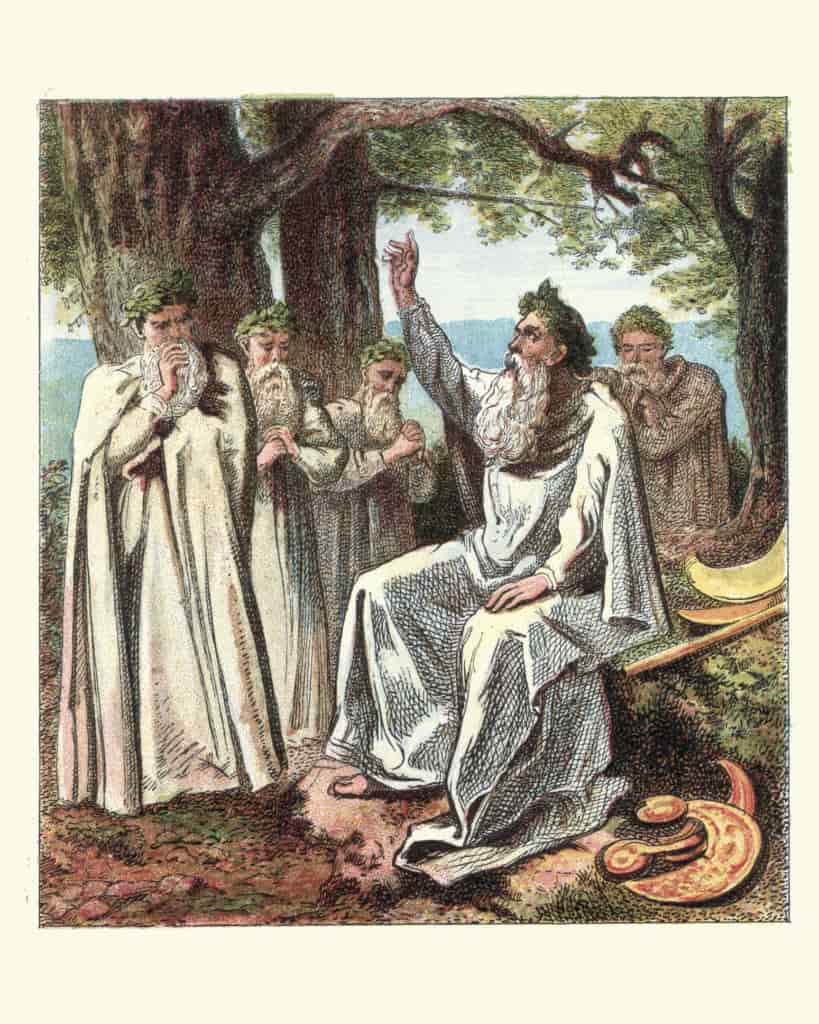

First up, the ancient Celts. The robes! The rituals! The love of nature! They divided the year into 12 months, and two periods: light and dark. It began with the darkness of Samhain (the Pagan and Wiccan New Year that snowballed into Halloween) on November 1st, and arrived at the light period, or Bealtaine, on May 1st. That evolved into the ancient Gaelic calendar, which was divided into four seasons, 12 months, and seven days of the week: Solis, Lunae, Martis, Mercurii, Jovis, Veneris, Saturni…

And it wasn’t just the Celts. It was the Romans. The ancient Hebrew, Japanese, Islamic, and Buddhist cultures– you name it, they had some form of a “lunisolar” (lunar + solar) that hinged not only on these two cycles, but on the importance of the natural world as the embodiment of their sacredness. Nature was the temple.

In our guide to esoteric Paris, you can see the traces of druidic time-telling devices in places like Saint-Sulpice Church on the Left Bank. Druidic stone circles are generally a great example of the painstaking efforts required for tracking the seasons with a lunisolar calendar.

These calendars literally moulded the landscape of our planet’s first cities, which erected grand temples and buildings to catch the light a certain way during the winter solstice, or illuminate a deity during in summer. They gave us Stonehenge. They gave us Chicen Itza.

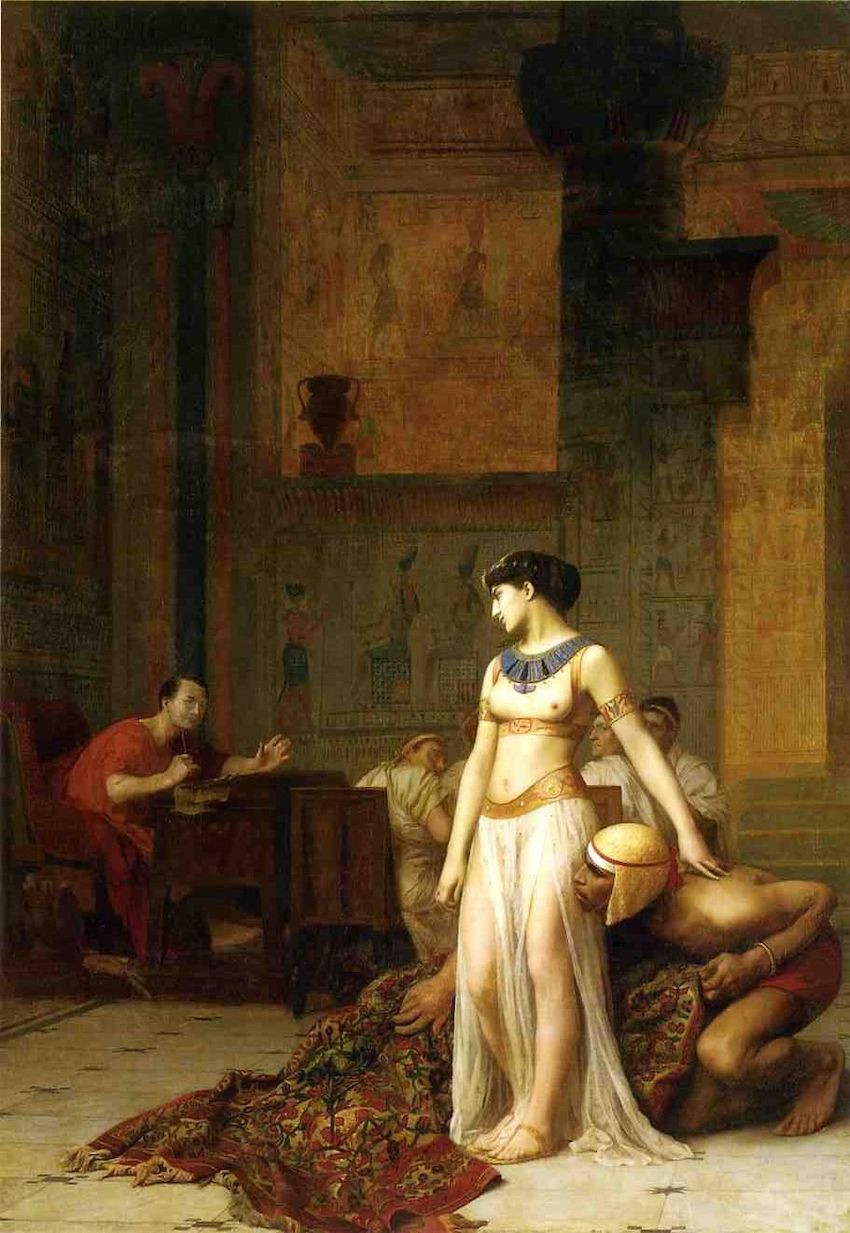

So why did the lunar die out? Well, you have to throw in a new month every 2-3 years to keep things in line, which gets tricky, when we consider how much our holidays would slip ‘n slide around. For example, is Guy Fawkes Day really Guy Fawkes day if it’s on the 28th of October? What about the 4th of the July? Seasons get out of whack. Cleopatra, for example, wasn’t on board with it (Egyptians followed a solar calendar). You can actually thank her – and her love life – for the calendar on your smartphone…

Rumour has it that during Cleopatra and Julius Caesars’ love affair, she convinced the emperor to drop the Roman lunar calendar (in which a year was 354 days long) for the solar. Julius’ calendar (aptly named “the Julian calendar”) even adopted the Egyptian leap year method of adding in a single day every four years to keep the calendar synchronised to the seasons, instead of a month every 2-ish years. Around 1582, Pope Gregory peppered in his holy days, and boom: the Gregorian calendar was born. Ever since that love affair, our global calendar has been a blend of that ancient Egyptian and Christian model.

The truth is, it took hundreds of years for the Western world to really adopt the Gregorian calendar, which was given the slogan, “The Improved Calendar.” Greece didn’t adopt it until 1923, and the island of Foula in Scotland still follows the Julian calendar.

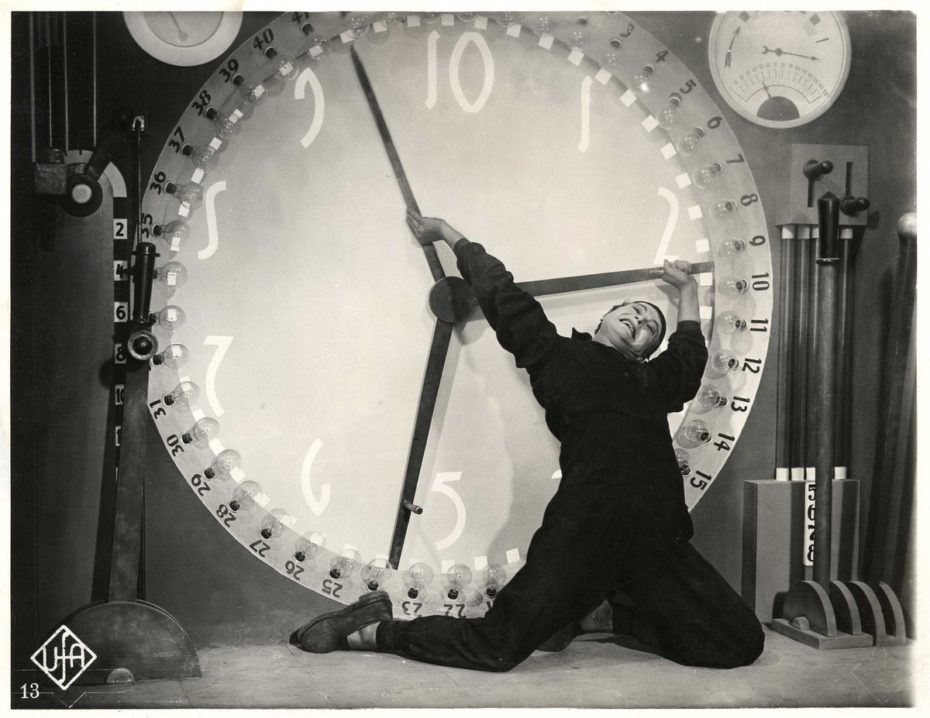

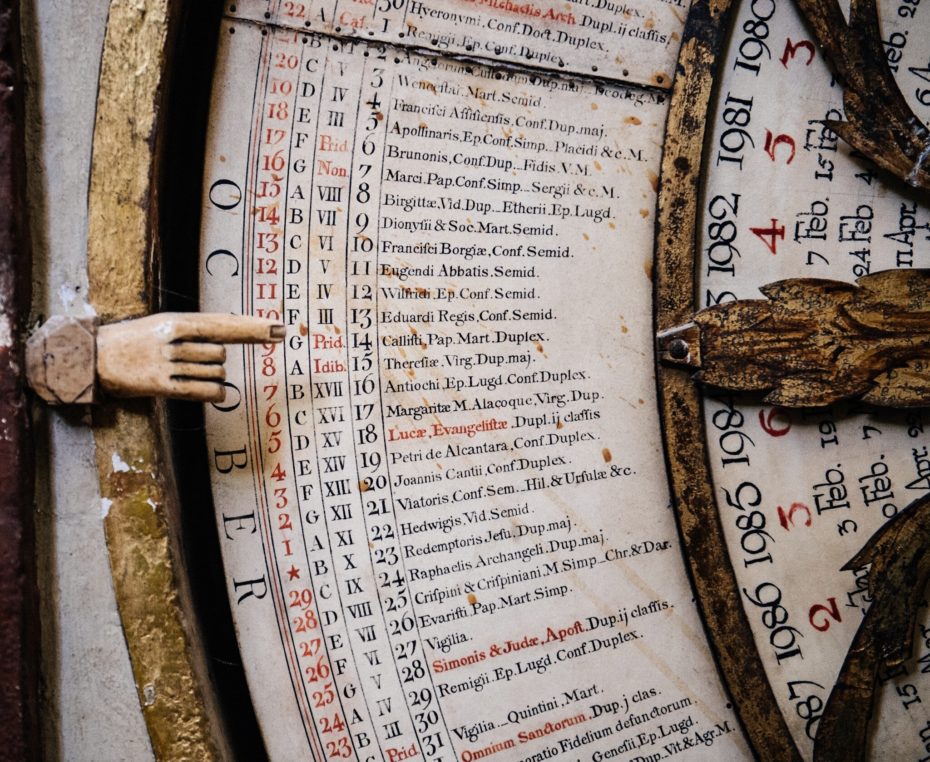

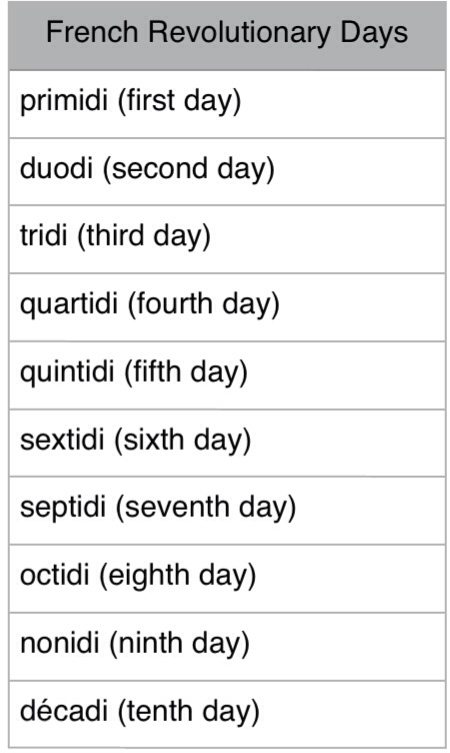

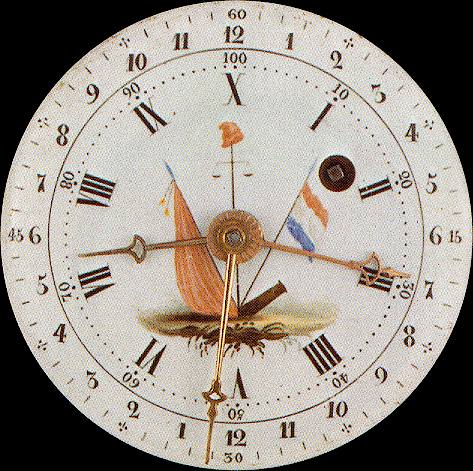

And then there’s the French, who for more than a decade after the French Revolution, switched to their own metric calendar, setting dates and times using a base 10 numbering system. After the monarchy was overthrown, the new Republican government birthed a radical new calendar that included a 10 day week (with a 9 day work week) that lasted from 1793 to 1805. The names of the week days, of course, were of all renamed.

Weeks became known as décades and there were twelve months in the calendar of exactly 30 days each – or three décades. The extra 5 or 6 days left over in the calendar (depending on the leap year) became holidays. You’d certainly need it after a 9 day work week.

Oh, and the year started on the Autumn equinox, which of course conveniently doesn’t fall on the same day of the year.

It wasn’t until Napoleon came along that it came to a halt, mostly because it was so damn confusing, but also because the church was still following the Gregorian calendar. Just making it on time to church or keeping track of important dates in the Christian calendar would have involved converting and keeping track of two different time systems. There are, however, still vestiges of that Revolutionary time across France in old monuments and artefacts. It also had a brief resurgence in the 1870s within the rebellious Paris Commune.

They weren’t alone in calendar reform. Let’s not forget to mention the French philosopher August Comte, who in 1849, proposed a solar calendar with 13 months, each 28 days long, with one extra day (“festival day” to commemorate the dead) to fill out a total of 365 days. It followed Gregorian leap year rules, but made what he saw as a progressive nod towards reason and Humanism by naming the months after men like Dante, Gutenberg, Shakespeare, Descartes, etc. It didn’t catch on.

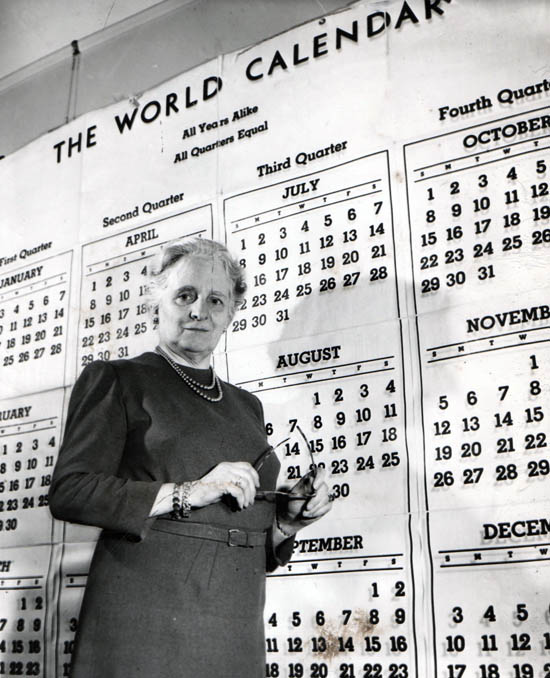

In 1930, a gal from Brooklyn named Elisabeth Achelis proposed a perennial, 12-month “World Calendar” made up of quarters of 91 days, with the obligatory bonus day being called simply “W” or “Worldsday” in-between December 30th and January 1st. For a hot minute in the 1950s, the United Nations really dug it – but major religious world leaders weren’t fans of nixing their holy days. The same went for other secular proposals. There was 1987’s Annus Novus Decimal Calendar, which envisioned 10 months with 7 weeks made up of 5 days. In 1998, a professor named Karl Palmen created a calendar system based on playing cards. And so on, and so on…

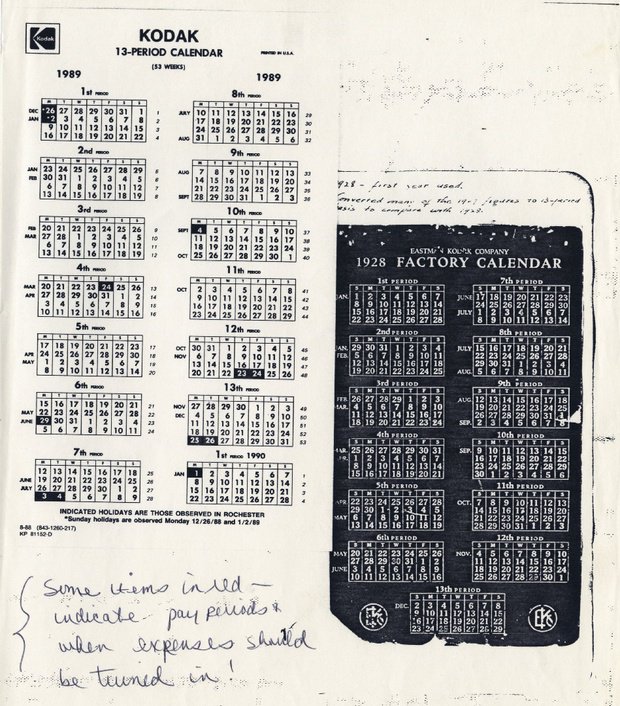

There was one 13 month calendar that had a good run. It was designed in 1902 by a guy named Moses B. Cotwsorth, who was your average, hum drum accountant for a British railway company. He just thought it would be easier for businesses to run on even 28 day months – and his pitch caught the attention of one of America’s biggest business tycoons, George Eastman, founder of Kodak and an eccentric of sorts.

From 1924 to 1989, he implemented Cotsworth’s calendar in his business, which declared an additional month between June and July called “Sol.” (in reference to summer solstice, which would include the leap year day every four days). It added up to 364 days, with an additional day: “Year Day.” He even brought the calendar reform before US Congress, and it was seriously considered by the League of Nations until WWII rushed in and put it on the permanent back-burner.

As time went on, our time became a reflection of increasingly complex, and industrial realities. In 1883, America’s rapidly expanding railroads decided to adopt different time zones – and while it’s always been Gregorian custom to take one day (Sunday) off for weekly rest, it wasn’t until Malcom E. Gray and Henry Ford came along that the two-day weekend was popularised, initially for factory workers.

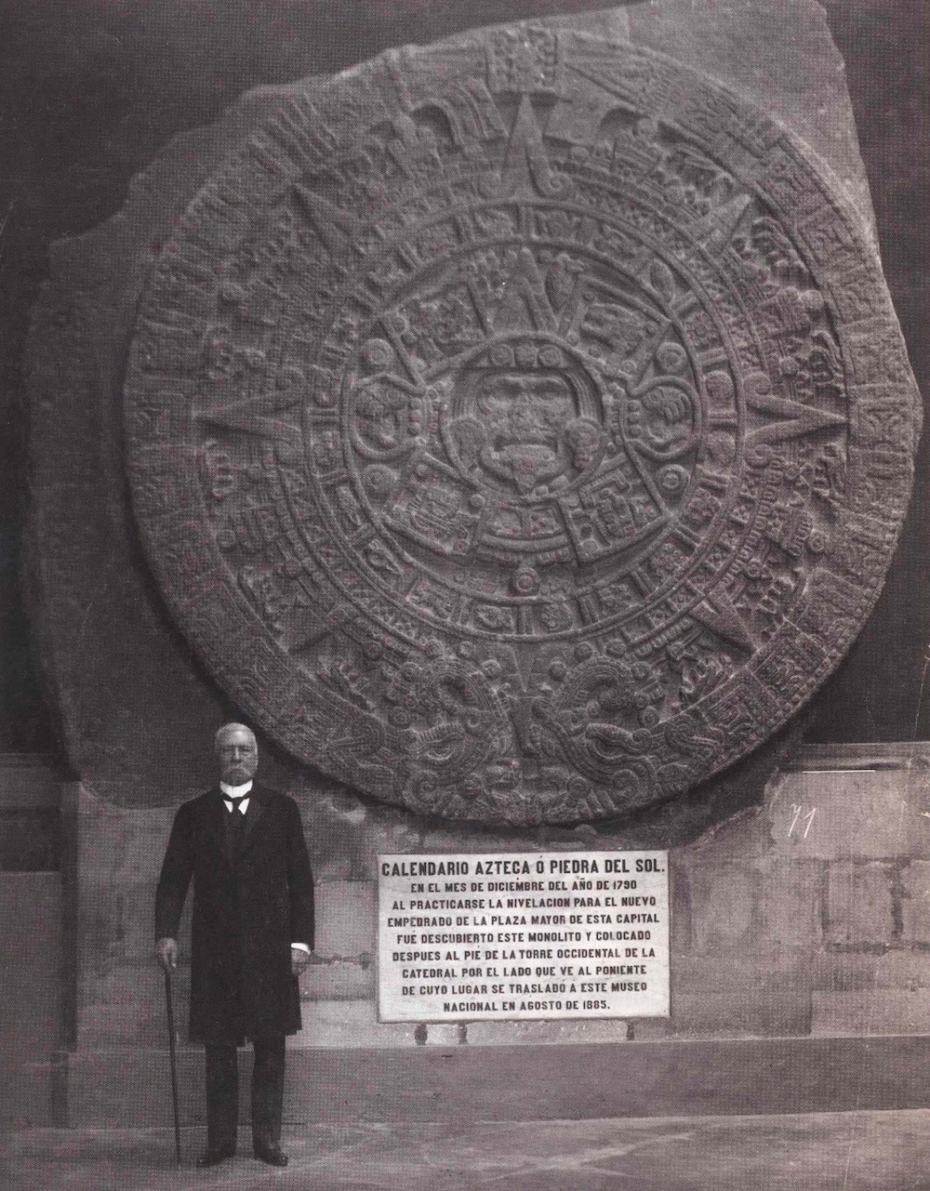

Then there are the ways in which we measure time without any formal ordinance. How long must a day have felt in the mud of a WWI trench? Contrastingly, “the world is born again when two people kiss,” wrote Mexican icon Octavio Paz in Sun Stone (in a poem structured around the Aztec “Sun Stone” calendar below). Paz stretched and trimmed that poem into a crisp 583 lines – precisely the number of days it takes for Venus’ rotation, which was a kind of calendar-within-a-calendar for the Atzecs.

So who wins? Nobody, and everybody. The world runs mostly Gregorian, but don’t let that stop you from tapping into your inner druid. At the end of the day, the root of every calendar can be traced to nature’s phenomena, to its magic. Sometimes we lose that magic in semantics; in the hustle of Time as it’s tamed by “the business quarter” instead of the poetry of Samhain. Culture, religion, social structure – all of these factors are ingredients in the sense-making of our primordial stew. The trick is to savour it.