As the 19th century came to a close and the 20th century picked up speed, people were absolutely held in thrall by the paranormal. Psychics and mediums sprang up everywhere as part of a movement called Spiritualism, and they promised to put people in touch with their departed loved ones. Mostly, they charged a fee, and customers came away believing they had paid for a magical experience. There were others however, who saw these mediums as con artists and frauds, preying on the grief-stricken in order to make a buck. With none other than Harry Houdini himself leading our real-life ghostbusters, these determined sceptics embarked on a very unusual and public campaign to prove to the world that they were being fooled.

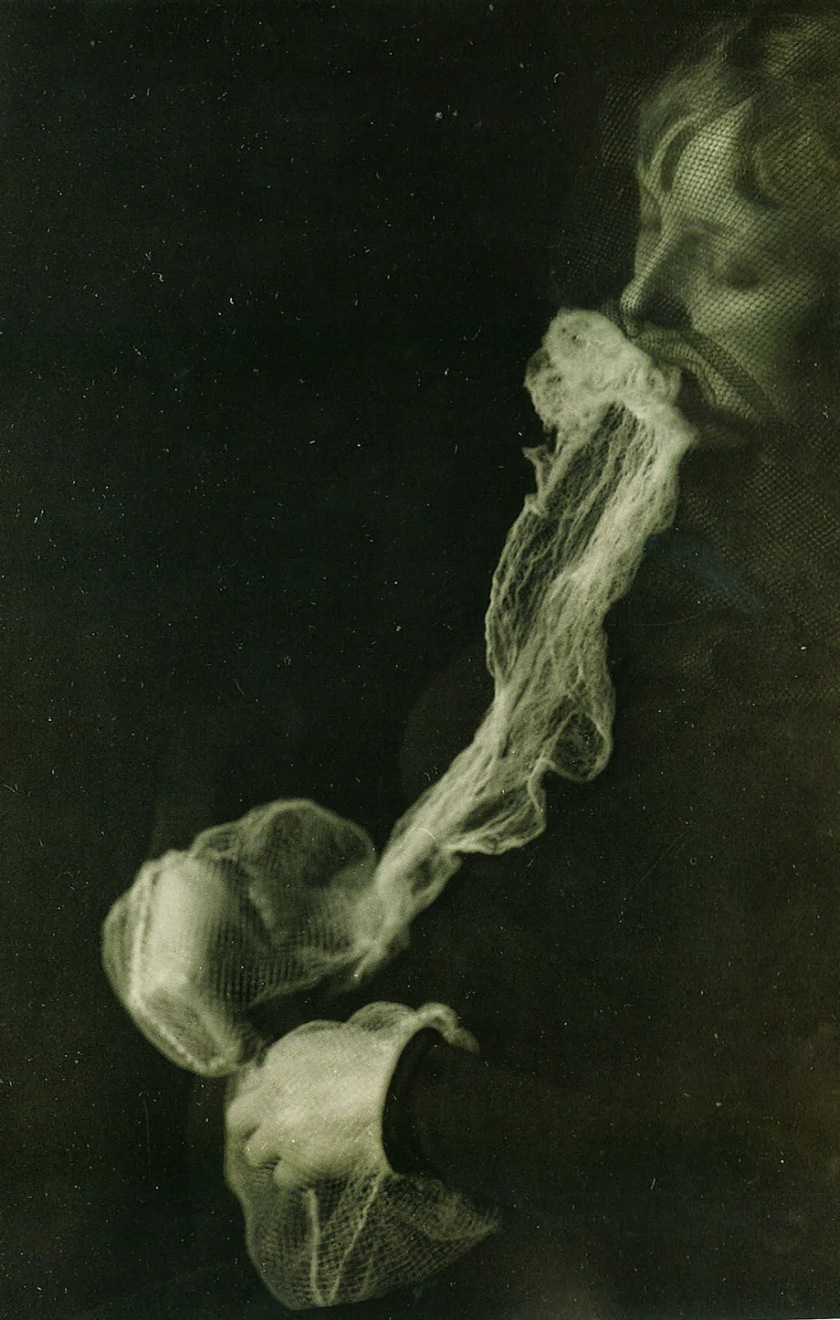

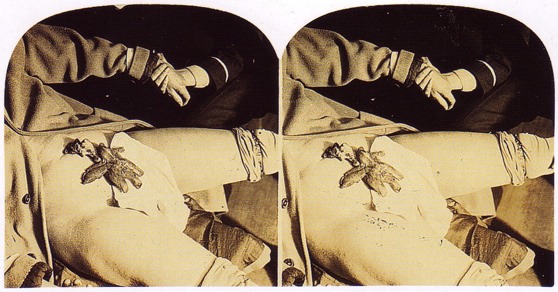

The great magician, Harry Houdini, known the world over for his daring escapes and feats of magic, had had his own brush with the spiritualists after the death of his mother. He had attended, by his own count, thousands of séances in order to try and reach her this side of the grave. After he became discouraged, he became suspicious. Being a master at sleight of hand himself, he soon began to notice the tricks and trappings that some mediums used to fool their customers into thinking that they really were being contacted by ghosts. There was the basic knuckle-cracking, foot tapping, and flickering candles that could all be explained as ghostly activity, but some of the most dedicated and successful con artists faked a substance they called ectoplasm, which would be externalized by the bodily orifices of the medium during a séance.

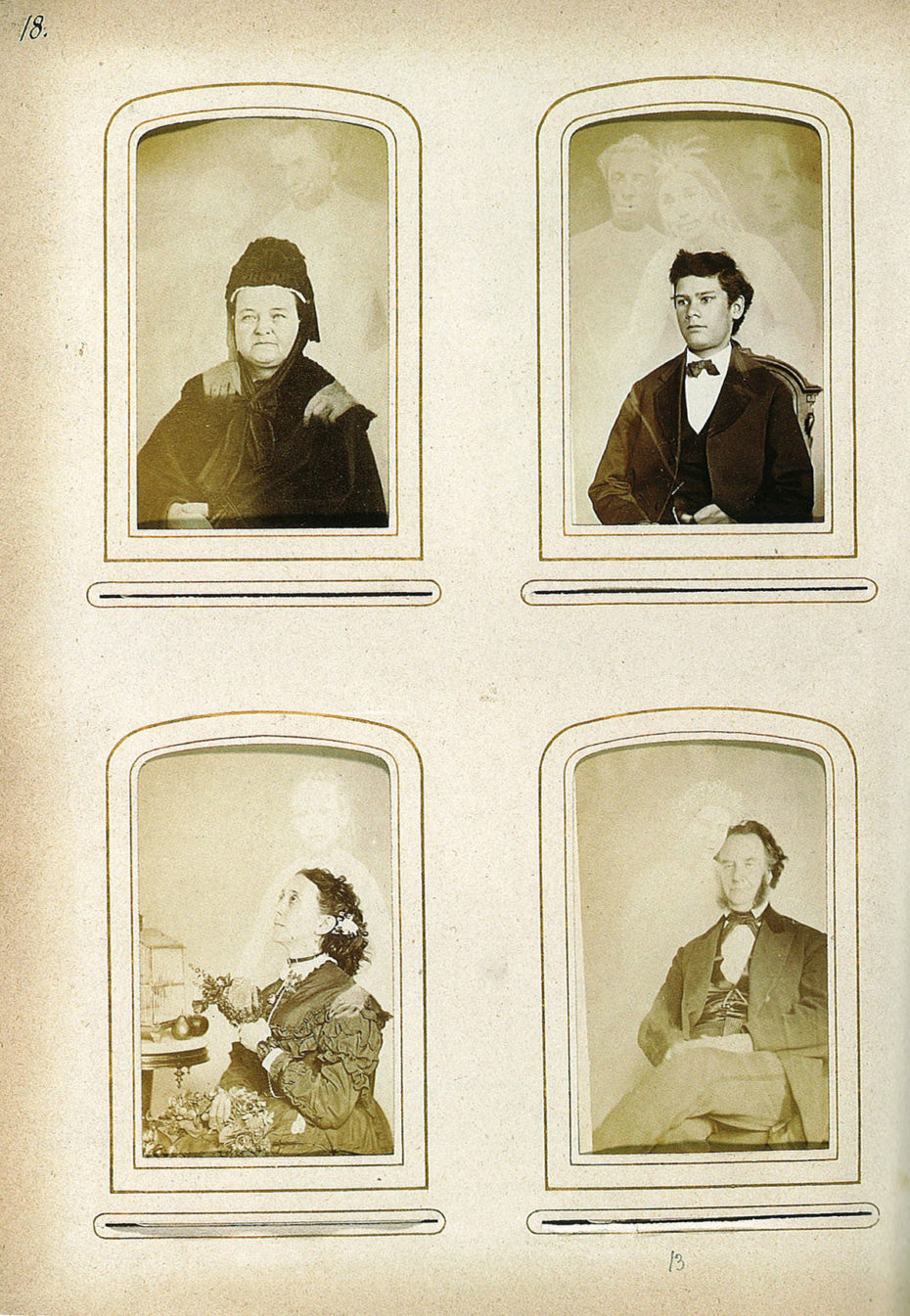

Vaporous in nature, it could take the form of a hand or a face. There was also an early form of photoshopping in Spirit photography. In 1924, Houdini wrote a book called A Magician Among the Spirits, which debunked many of the ways in which mediums tricked the public in the name of spiritualism. But he wasn’t done there.

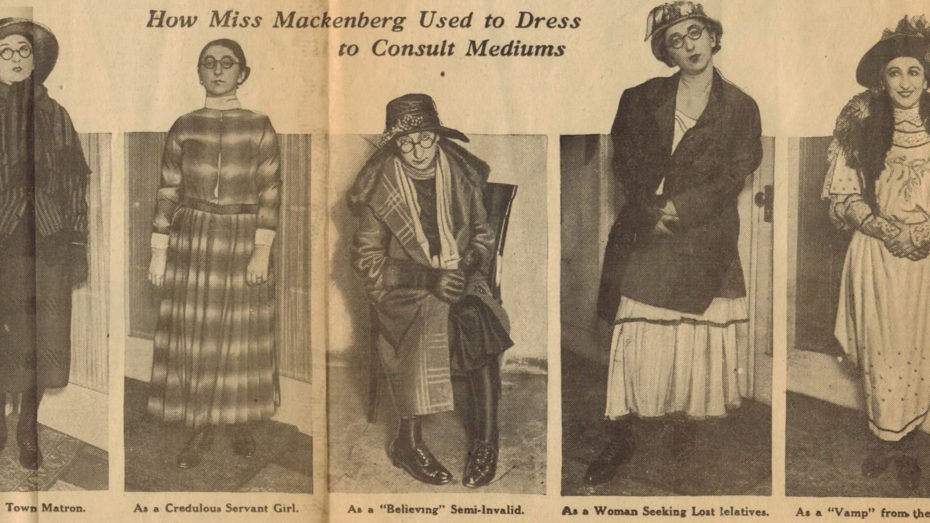

Enter Rose Mackenberg, from Brooklyn, New York, who by her early adult years had been working as a stenographer in a law office. As fate would have it, a client of theirs sought legal aid when his investments took a nose dive after following the advice of a medium. As Harry Houdini was already well known for his work exposing fraudulent mediums, Rose went to him directly to consult on the case. By all accounts, Houdini was impressed with Rose, and offered her a job as an undercover investigator with his band of skeptics who were all tasked with attending séances and meetings with mediums to unravel their ruse. Then, he would confront the mediums publicly, usually at one of his shows in order to best expose them. Investigators would accompany Houdini on tour, but roll into a town a few days or a week early to do the field work. Rose quickly became his chief investigator accomplice.

She donned disguises and created fake personas such as “rustic school teacher”, “tipsy consultant”, and “credulous servant girl”. She was smart, thorough, and very, very believable. She used names like Frances Raud (F.Raud) and Allicia Bunk (All Is Bunk) and was amused by psychics who claimed to have had contact with her deceased husband, despite the fact that she never married.

Rose Mackenberg worked with Houdini until his death in 1926 but would continue to investigate and expose mediums long after. Fellow skeptics held her in a kind of reverence. Many spiritualists, however, were angry. They had threatened Houdini to the point that he carried a gun. Rose refused to do so, against her employer’s advice.

P.T. Barnum, aka “The Greatest Showman on Earth”, the king of Victorian era sideshows, was another public figure who was very publicly opposed to psychics. In particular, Barnum went after Spirit Photographers like William Mumler, who had made a career of layering portraits of his clients with images of their deceased loved ones. A mother might be sitting with a pale ghostly outline of her dead son standing solemnly behind her. He claimed that his photographs were not tricks, and that they actually captured ghosts. Mumler’s most famous picture shows Mary Todd Lincoln with what is supposed to be the ghost of her deceased husband, Abraham Lincoln.

P.T. Barnum took great offense to the dishonest practices of people like Mumler, possibly because the public often put the Spiritualists and his Sideshow acts in the same box. Didn’t Barnum also make his money fooling people? The difference, as Barnum would point out, is that people expected him to fool them in the name of entertainment. Barnum even submitted evidence in the case against Mumler in 1869, a photograph of himself with the late Abraham Lincoln, showing the jury how easy it was to fake photos of ghosts. Barnum also accused Mumler of using photos of living clients without their consent to create ghostly images to fool other customers. Despite this, Mumler ended up being acquitted. The jury, they said, could not prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the photos were not faked.

Meanwhile in England, British psychic researcher Harry Price was waging his own war against mediums. He had initially been a member of the Society for Psychical Research in 1920, but became at odds with the group over his practice of paying the mediums he was investigating. Price took on cases against Britain’s most popular spirit photographers and mediums. He did his homework and found success. One of his notable cases was against Helen Kerr, a psychic who made a name for herself by spewing ectoplasm from her mouth during séances. Kerr greed to sit for an investigation, but ran from the room screaming when Price requested an x-ray. During a subsequent investigation, Price and other psychical researchers sat with bated breath, waiting for Kerr to produce the famous vaporous spirits from her mouth. When she finally did, they leapt to collect a sample, only to sure enough, find it was paper soaked in egg whites. In 1925, he founded his own organization called the National Laboratory of Psychical Research. These were the days in which numerous societies, both for and against Spiritualism, were finding widespread support.

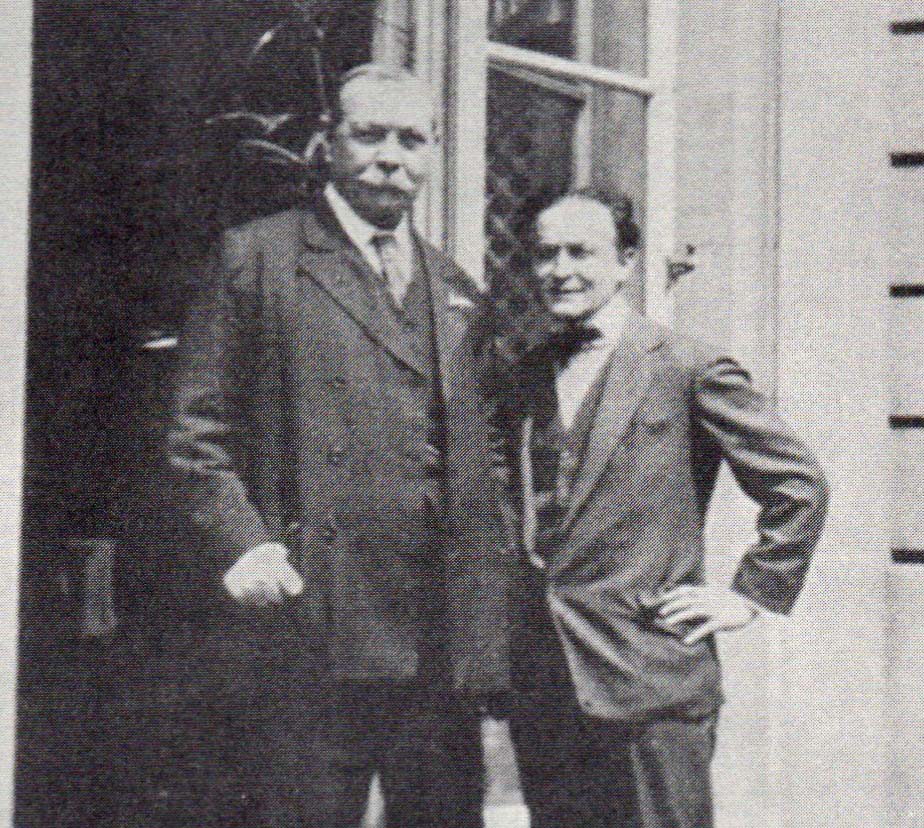

One of the most notable adversaries of the ghost-busting skeptics was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who you might know as the author and creator of Sherlock Holmes. In the 1880’s, while Doyle was still in medical school, he began to question whether or not life truly ended at death. He wondered if the spirit might prevail in some way. Doyle’s fascination with the question of what happens after death only grew, and he became an ardent supporter of the Spiritualism movement and its mediums. He was not alone in his beliefs, and in 1893 he joined The Society for Psychical Research, an organization which still exists today, formed by individuals who were devoted to researching instances of the paranormal, psychic, or unexplained. A strong believer in the practice of trying to contact the dead, Doyle attended séances, performed investigations to prove the truth behind mediums and psychics, and wrote extensively about his beliefs. When he lost his son, Kinglsey to a combination of battlefield injuries suffered in The Great war, and Spanish Influenza, Doyle’s beliefs comforted and sustained him.

When two teenage girls took a series of photos in 1917, which claimed to have captured a group of fairies they played with in the woods, the entire country, the British public became enthralled by the story of the Cottingley fairies. Photography was still a fairly new art, and many people hotly debated whether or not the photos were real. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle famously declared them to be genuine.

In 1922, he developed an unexpected friendship with Harry Houdini at a lecture on Spiritualism in America.

On stage, he projected a movie that appeared to feature live dinosaurs on the screen. Houdini was in the audience, and along with the rest of the crowd, couldn’t believe his eyes. No one, not even the great magician, could explain how dinosaurs had been captured on film, and Conan offered no explanation. But the message was clear: do not so hastily dismiss phenomena you do not understand. The film, an excerpt from an upcoming movie based on his novel, The Lost World, was of course, stop-motion photography of miniatures, the first of its kind. From then on, despite their differences, Houdini became an admirer and friend of Doyle.

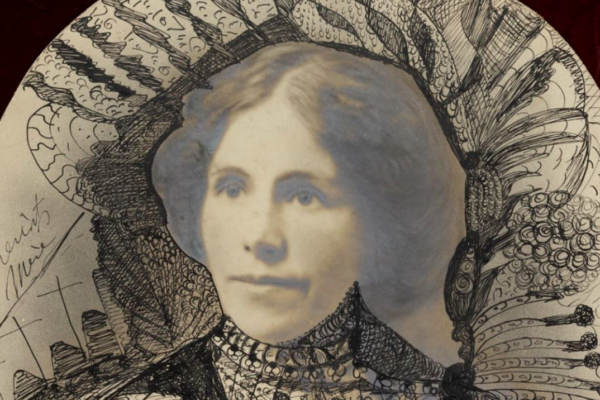

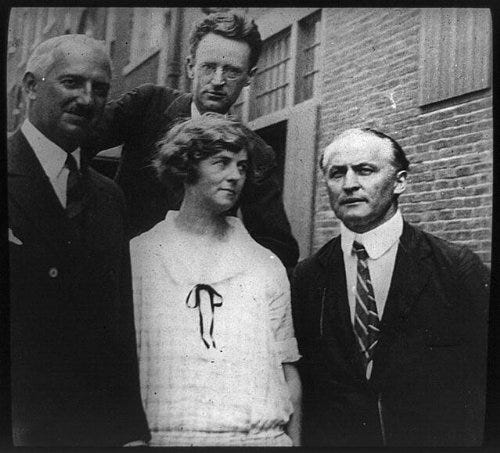

In the 1920s, Doyle also became a devoted defender of Margery “Mina” Crandon, a young, bright eyed, and beautiful woman who had risen to fame with her notorious séances. Reportedly she oozed ectoplasm out of her eyes and ears, but what really got her clients attention, was that she performed them in the nude. In Boston, where she lived, she was known as “The Blonde Witch of Lime Street”. Men accused her of being too attractive and loose, sitting in men’s laps while communicating with their deceased loved ones. Mina’s life has been well documented by the psychical research community.

Doyle’s name became indelibly linked with hers after he supported her during the scandal of the Scientific American prize. In 1924, when America was engaged in a white hot debate over the credibility of the Spiritualism movement, the Scientific American offered a prize of $2,500 (about $40,000 today) to any psychic who could demonstrate to an esteemed six-man committee a “visual psychic manifestation.” For someone who held the country in her thrall, and who had the likes of Doyle and his followers ready to come to her defence, she accepted the challenge. The six man committee consisted of a Harvard psychologist, an MIT physicist, two members of the American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR), the chair of the committee of Scientific American, and none other than Harry Houdini. Mina had her work cut out for her trying to prove herself.

The two members of the ASPR were familiar with Mina’s work, and had already attended many séances with her, only to be wowed by her abilities. They were ready and willing to award her the prize on the spot. The others, though, took more convincing. Houdini was absolutely outraged at the tricks she was playing on her audience during her psychic session and accused her of all kinds of simple but effective special effects to fool people. Over several sessions, Houdini insisted that she have her arms and legs restrained to prevent her from using them to create ghostly noises and other trickery.

The committee remained conflicted and divided. They asked Houdini to hold off on publicly declaring his opinions on Mina, which only made him more frustrated, so he decided to exact justice in his own way. He created an act for his travelling shows that mimicked Mina Crandon’s séances, in order to humiliate her and show audiences just what kind of a con she was running. Alas, Mina did not win the prize, but she may have had the last laugh. After Houdini’s death just two years later, Mina continued to perform and hold sway with believers for decades to come. Many people discredited her, but perhaps more held her up as a shining example of the power of Spiritualism.

The American Society for Psychical Research still exists today. From 1966 to 2019, their headquarters were located in a beautiful Beaux-Arts style mansion located at 5 West 73rd Street in Manhattan (they sold it in 2019). It maintains offices and a library, in New York City, which are open to both members and the general public.

Their website describes their mission as, “… to explore extraordinary or as yet unexplained phenomena that have been called psychic or paranormal, and their implications for our understanding of consciousness, the universe and the nature of existence”. While they have been around for more than a century, in 1925, after the Mina Crandon Scientific American episode, they split into two different factions. The original ASPR came out heavily in support of Spiritualism. The other, renamed Boston Society for Psychical research (BSPR) was made up of supporters who saw Crandon as a fraud. They framed their group around telepathy and continued to distinguish themselves from ASPR for several decades, but slowly faded. Eventually they were reabsorbed back into the bosom of ASPR in 1941.

Spiritualism doesn’t ignite the country like it did in the late 19th and early 20th century, however, people have not lost their fascination with life after death. Consider how many ghost hunting shows are still on TV! It’s still a controversial subject and the paranormal debate may never settled. The next time you’re at a dinner party – ask who believes in ghosts and see if the opinion isn’t split down the middle….