Hailed as the most powerful woman in media, Anna Wintour has been fictionalised, caricatured and propelled into icon status since becoming editor-in-chief of Vogue. Then there’s Diana Vreeland, editor of the American style bible between 1963–1971, an industry legend who was the driving force of the Met’s Costume Institute, and styled a persona that would be remembered as one of fashion’s most eccentric and quotable cult figures. But Grace Mirabella is a bit like the middle child of Vogue‘s 20th century story. Sandwiched in between Wintour and Vreeland, she was at the helm of American Vogue throughout the 1970s and much of the 1980s, and steered the ship during a revolutionary new era of working women putting their careers first. Somehow though, Mirabella faded into the background of fashion history. Despite a career that arguably changed the course of fashion history, rarely, if ever, do you hear today’s tastemakers or “It Girls” referencing Mirabella as their fashion heroine. And in all honesty, we barely knew anything about her either. So this is us, getting to know contemporary Vogue‘s “least famous” editor.

The Devil Wears Prada’s Miranda Priestly may have embodied the stereotypical fashion editor of the 20th century (pre-cancel culture) – a fearsome, all-powerful style queen who threw her jacket at minions and delivered her orders with a sting. Grace Mirabella was not that. Instead she was serene, calm and unflappable. It’s this temperament that let Grace Mirabella navigate American Vogue swimmingly through the sea changes of the 1970s and 1980s. Her trademark style was one of propagating a relaxed American fashion culture that sat comfortably somewhere between the innocent swing of the sixties and the corporate bling of the eighties. Grace Mirabella brought a new sensibility to the world of fashion media and championed a wholesome, healthy American lifestyle and with it, practical, no-nonsense, easy-to-wear fashion. To boot, she single-handedly managed to expand Vogue’s readership and turnover.

It’s no secret that the rag trade is a fickle business and at the mercy of socio-political changes and cultural norms. At the best of times, fashion trends themselves are a rollercoaster, changing direction and velocity at the drop of a hat. With ever-shifting horizons a captain who can steer a ship through the quicksilver waters of volatility is worth their weight in gold. Grace Mirabella was such a commander.

Marie Grace Mirabella was born in New Jersey of Italian descent. Having grown up in a debt-ridden family, she managed to gain an economics qualification and went into the fashion world as a shop girl in a friend’s shoe store, later working her way up to a sales job at Macy’s New York and Saks Fifth Avenue. In 1952, she got her foot in the door at Vogue magazine as an assistant.

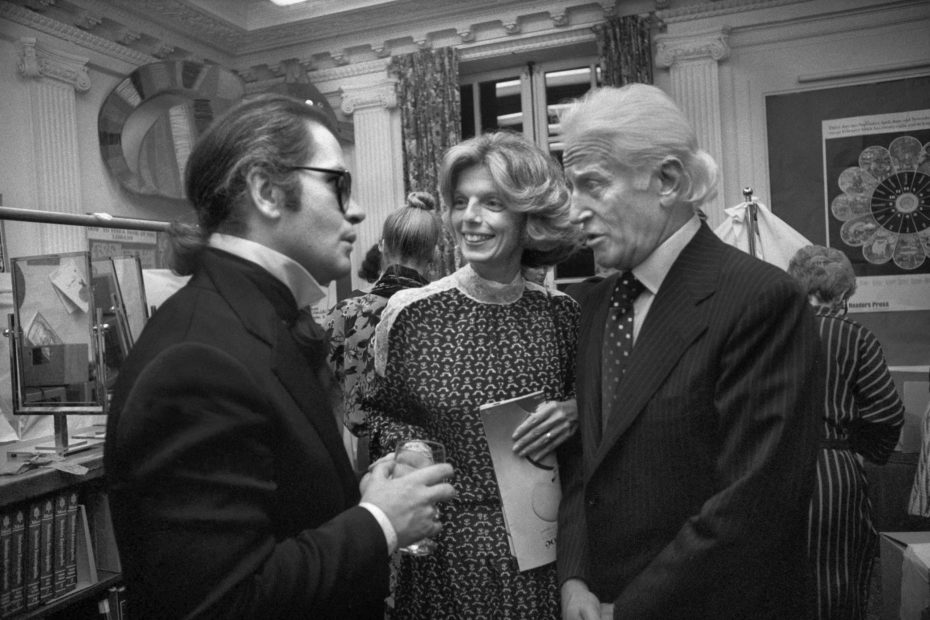

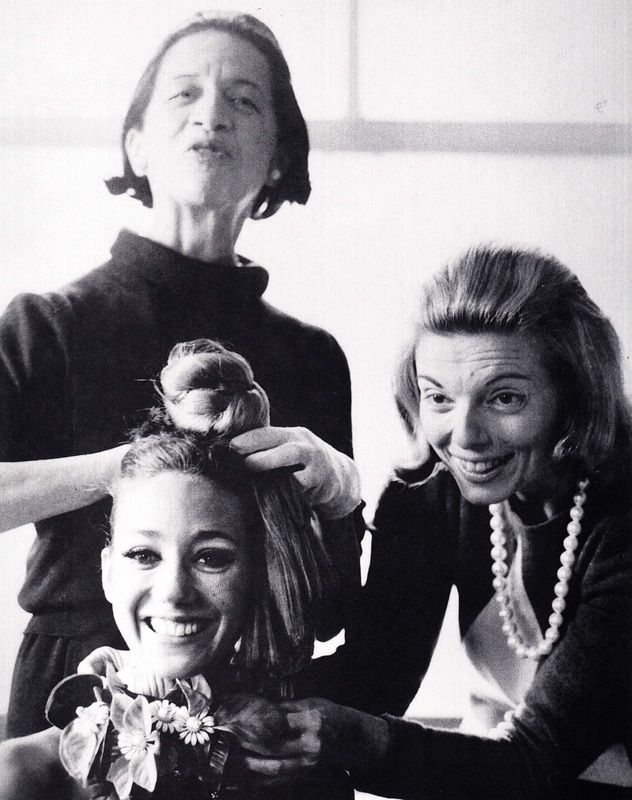

By the 1960s, Grace became an associate editor under the then editor-in-chief Diana Vreeland. Grace reportedly had a school-girl crush on Vreeland and followed her around like an obedient puppy, learning the trade as she went. She said recalled, “It was very difficult to work for her. But you can get along with someone who is difficult if you admire them.”

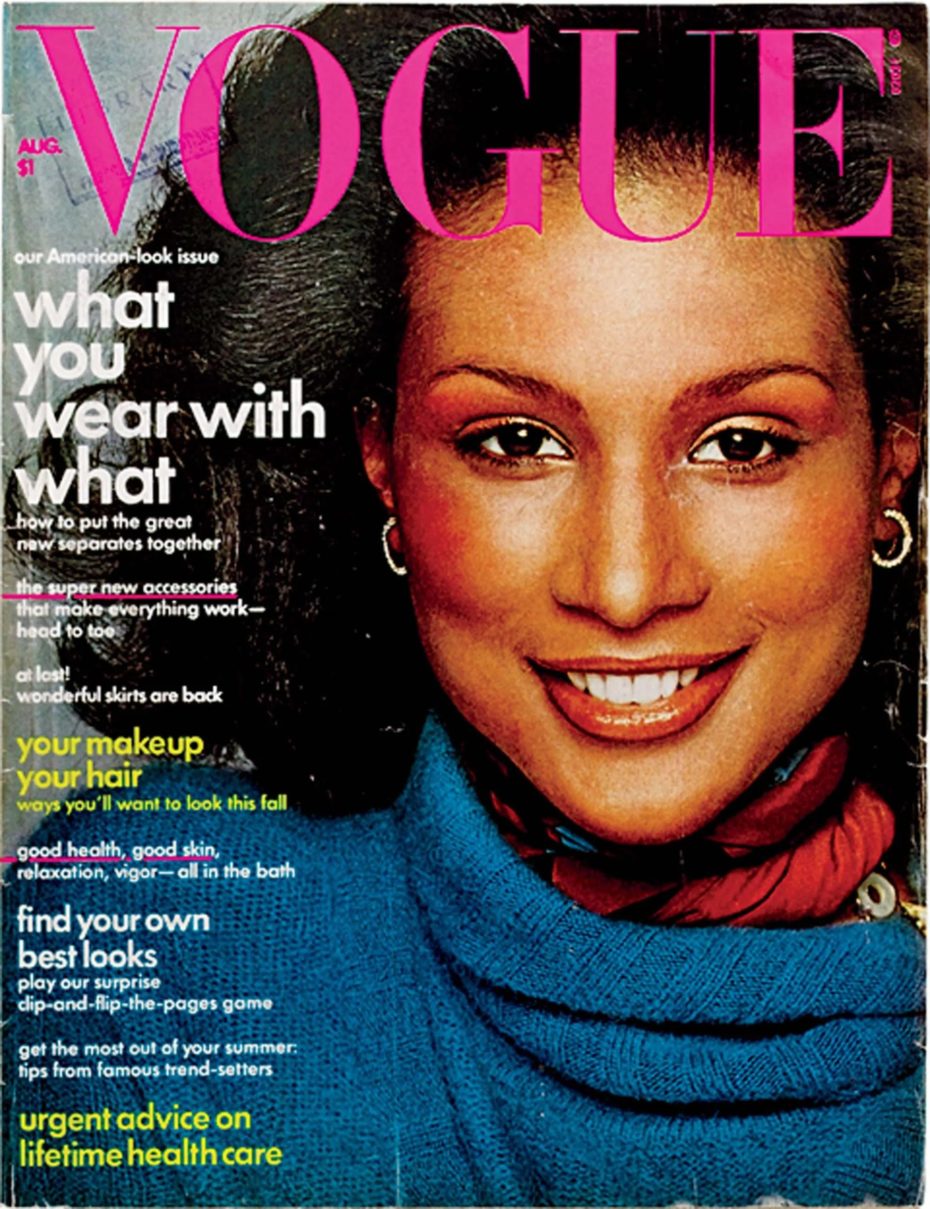

It was around this time that the big bosses at Condé Nast felt that Vreeland’s treatment of ‘fashion as theatre’ was not a sound base to continue, far less to expand the magazine into a changing future. Grace controversially replaced Diana in 1971 as editor-in-chief with a clear vision to ‘democratise’ the magazine and bring it to a wider audience, offering accessible fashion to a new, empowered, middle-class female readership. She also made history within the first few years of her reign by by featuring Beverly Johnson on the cover of the August 1974 issue, making her American Vogue‘s first Black cover girl.

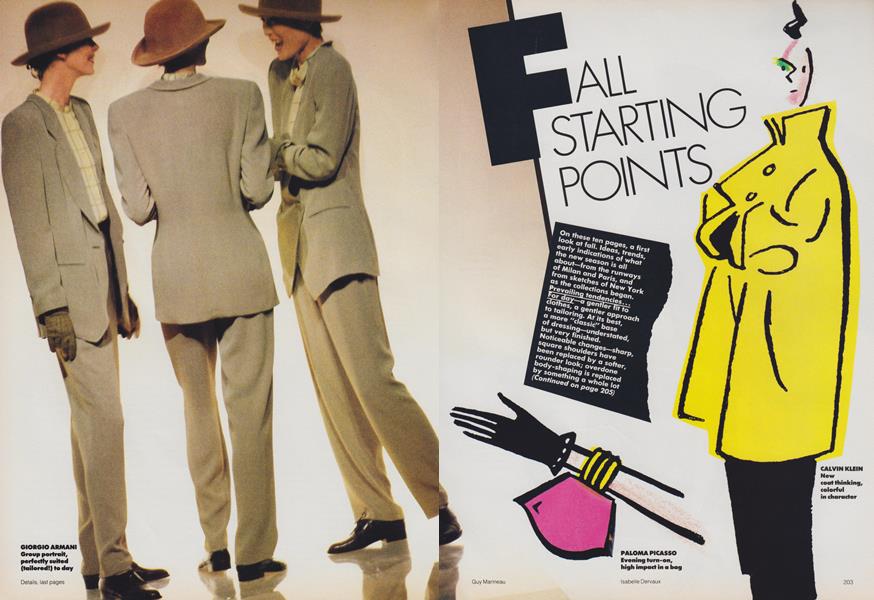

Grace’s tenure is regarded as bringing Vogue – often accused of catering to the ‘airy-fairy’ fashionista – back down to earth. Her approach had a much broader appeal, attracting the new career-based ‘modern woman’, swapping elite fantasy for practical minimalism. Grace’s Vogue content was very much a broad church, encompassing arts, lifestyle, cosmetics, health and fitness and all this of course on the back of good, wearable ‘American’ clothes. From her youth, wartime need and austerity had convinced Grace that women could look great in good working clothes and ready-to-wear outfits. The war had brought not only practicality (the ‘make do and mend’ mentality) but increasing social change. Post-war America was cool and casual, there was a new-found freedom in choosing how to behave and how to dress. Clothing was becoming more relaxed and unisex, classic jeans or beige slacks and T-shirts with over-the-shoulder pullovers became overnight staples. Think Meg Ryan style Diane Keaton circa Annie Hall.

A sensible Grace had very little interest in passing trends and firmly believed clothes should have longevity and be proper workhorses in the wardrobe. Of trends she famously said, “You’ll never find me getting excited about shoulder pads or caring deeply, one way or the other, if hemlines went up or down.” Instead, her ethos was for women to develop a personal style.

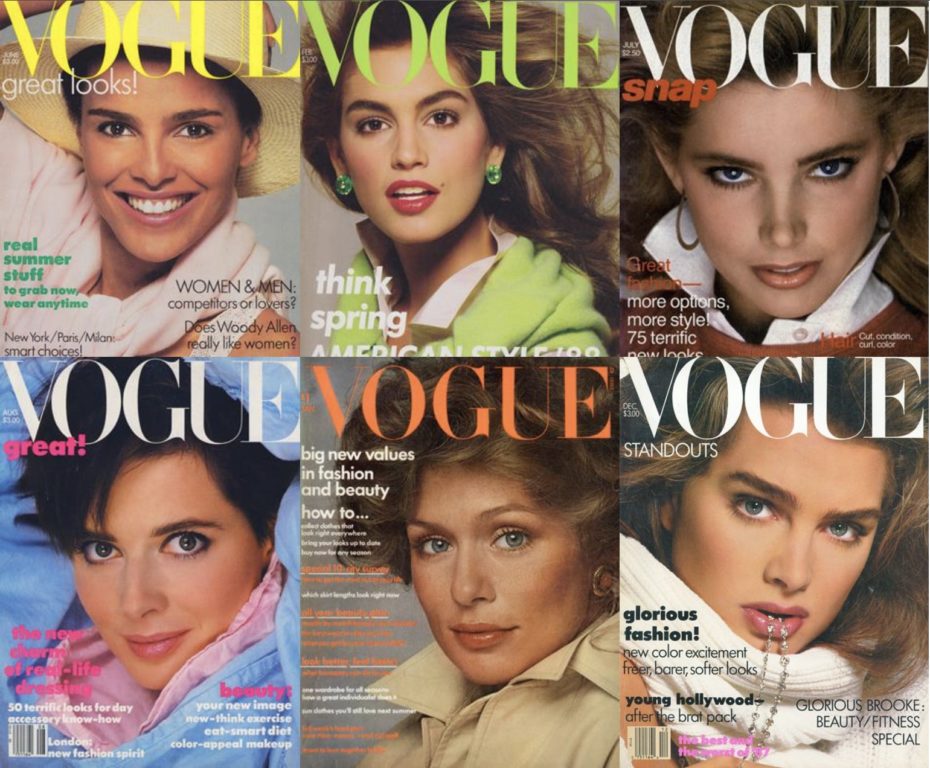

She promoted and showcased the now legendary photographers Helmut Newton and Richard Avendon, who worked on the covers from 1971 till 1988 during the early supermodel years. Her cover style was distinctive: predominately exquisite close-up portraits of classically-styled young women gazing out to catch the attention from the news-stands.

Prior to and post Grace, the style was less rigid, with more full figure photographs, where the smaller facial image would be less engaging. New Fashion designers like Yves Saint Laurent and Ralph Lauren were regularly featured. Way ahead of the ethos of her time, regarding tobacco products, she engaged in an anti-smoking campaign by limiting tobacco advertising space in Vogue. Under her leadership, the magazine flourished, and she attracted a vast new audience – advertising revenue was almost double that of French international rival Elle and circulation went from 400,000 to 1.2 million.

Grace Mirabella was unceremoniously replaced by Anna Wintour in 1987. The move was ruthlessly orchestrated by Condé Nast owner Si Newhouse. The corporate world as well as Grace herself, only learnt about it on the news. As the 90s approached, Elle magazine, with its vibrant and youth-focused content had overtaken Vogue in reader numbers. A new approach and fresh blood were required to restore Vogue as leader of a new and flashy world, focusing on a more glitzy and theatrical fashion spectacle rather than on lifestyle and practical content. Grace bitterly complained about the exaggerated and excessive fashion of the 1980s. “I couldn’t stand the frills and the glitz and the 40,000-dollar ball gowns,” she said.

Grace’s tenure, despite being very successful at Vogue, would be cruelly known as ‘the beige years’ referring to the colour of her office walls – she had repainted the red walls of Vreeland’s office repainted in shades of beige, her favourite colour.

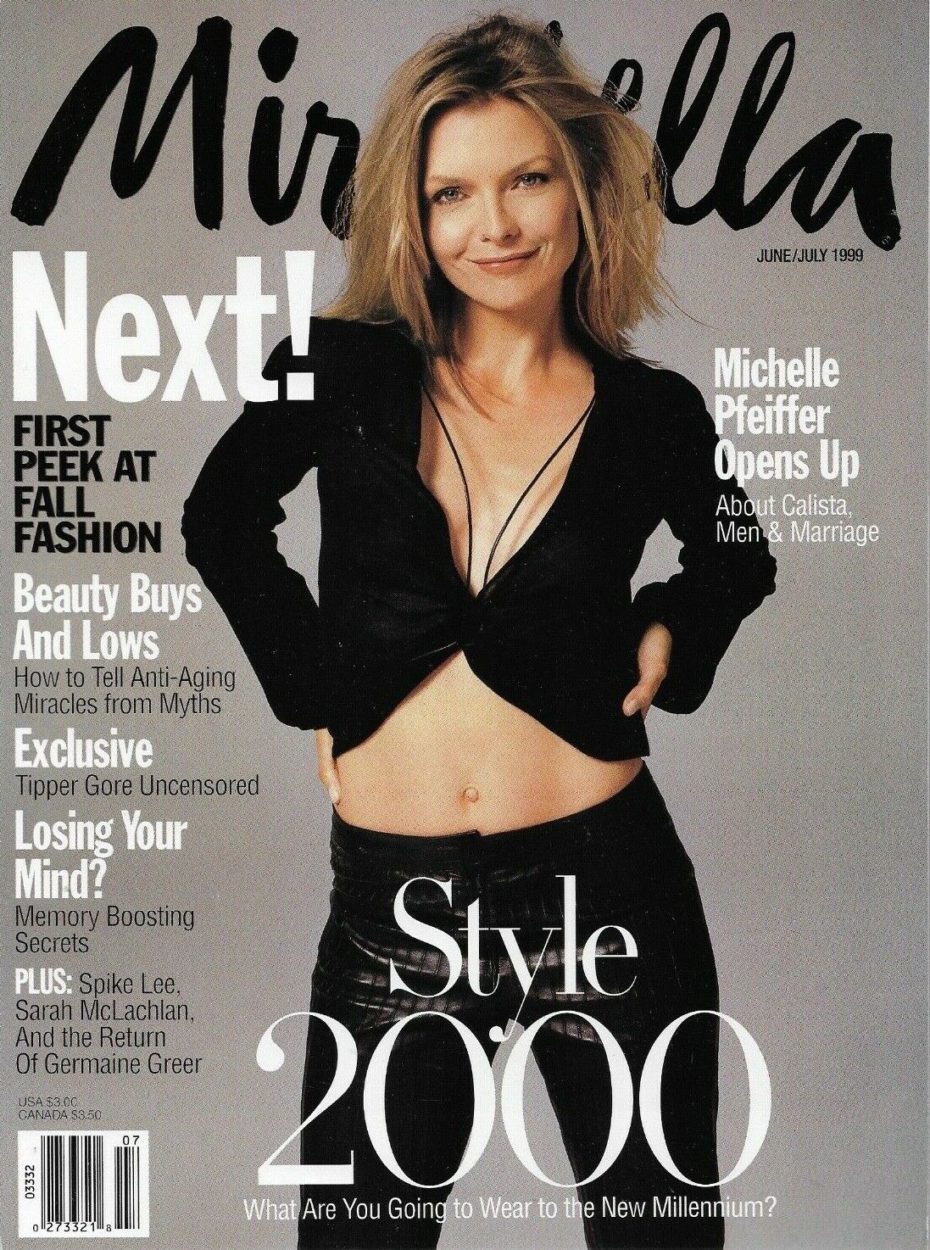

With the financial backing of none other than Rupert Murdoch, Grace launched her own magazine, Mirabella in 1989. Aimed at middle-aged American career women, it again focused on lifestyle advice and casual, relaxed and practical fashion. In a bizarre twist of fate, the magazine originally published by Murdoch’s News Corporation became the property of Hachette Filipacchi, the owners of Vogue’s arch rival Elle Magazine, in 1995.

Mirabella magazine shook off the rigour and formality of Vogue, the tone of the magazine promoted well-chosen style, not object-based trendiness, but a relaxed lifestyle content for established women, with culture, travel and the arts as key components. Fashion was always the backbone, but well-designed and practical, neither elitist nor ‘ridiculous’. Her influence at the magazine declined in the 1990s and she eventually left in 1996. Perhaps her approach was a little too serious, a little too ‘high-brow’ and not offering the pure escapism of her competitor publications. The readership had also fallen and the magazine was closed in 2000 with a circulation of 550,000 from a start of 400 000.

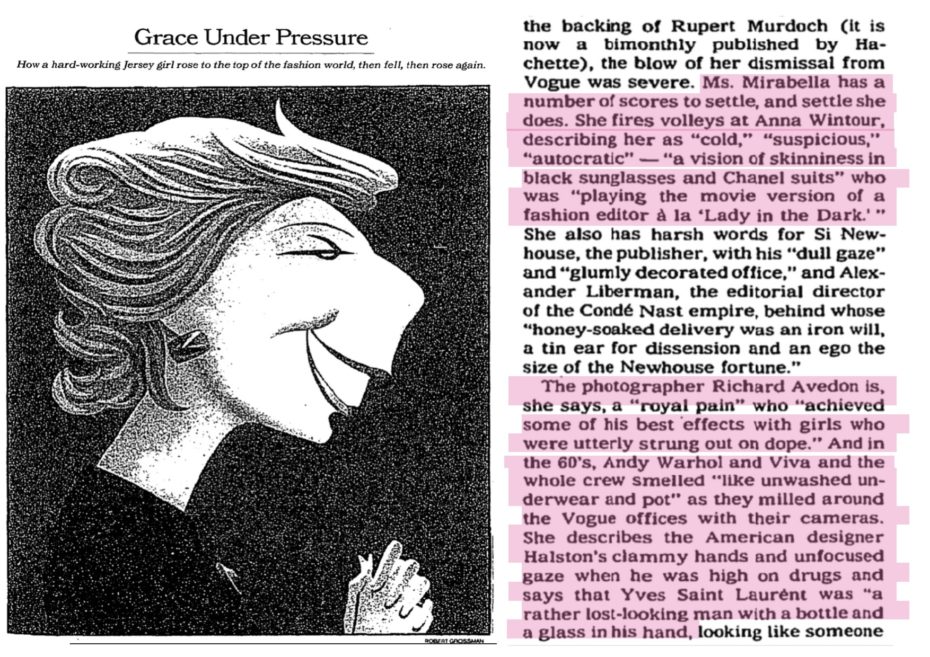

At age 66, Grace wrote her autobiography ‘In and Out of Vogue’, describing her 38 years in the fashion industry. As highlighted in The New York Times review of her book, she had some fighting words in hindsight about many of fashion’s most high profile figures, from her successor Anna Wintour to Andy Warhol, who had shared his own theory with the press on Grace’s exit from the style bible, remarking “she was fired from Vogue in 1971 because Vogue wanted to go middle class.”

Grace continued to write a column for New York-based society publication Quest Magazine and in 2012 launched the online fashion and lifestyle magazine The Aesthete. In her memoir in 1995, she said of fashion, ‘What I’ve always cared about, passionately, is style. Style is how a woman carries herself and approaches the world. It’s about how she wears her clothes and it’s more: an attitude about living.”

Grace died on December 23, 2021 at the age of 92 at her home in Manhattan.

If Condé Nast’s international fleet of Vogue magazines are the Holy Bible of fashion monthlies, American Vogue is the jewel in its crown. And keeping that jewel safe requires a pair of steady hands on the tiller, the wisdom of Solomon and plenty of nerve. Grace Mirabella rather stylishly and serenely pulled that off and more: she grounded the fashion industry while keeping her elegant finger firmly on the pulse of society. And in case you didn’t hadn’t noticed the latest trends – beige is the new black.