“We don’t embroider cushions here,” said the man considered as the most important architect of the modern age, during his first encounter with Charlotte Perriand. She wanted to work for Le Corbusier, a name synonymous with those dramatically new brutal concrete buildings, rejecting the past, promising a utopian future. He would take some convincing to hire Perriand, an exceptionally talented and productive architect who would spend decades working in his shadow, eventually to emerge as a tour de force in her own right, with her design ideas now very much aligned with current sustainable thinking. Charlotte Perriand saw the future, perhaps more clearly the Le Corbusier and his modernist boys club. You know her designs even if you don’t think you do – in fact you’ve probably had one of IKEA’s many best-selling pieces in your apartment without knowing it was directly inspired by the quiet genius of Charlotte Perriand.

Radical political change throughout 20th century society is perhaps best reflected in its architectural and design expressions. The “International Style” emerged post-WWI out of social change to serve an expanding and more egalitarian society: populations demanded new products, free from the hang-ups of the old ‘Victorian’ world. Nationalism promoted the rise of their celebrities – those who could carry the flag and further the profile of the country. Corbusier, although born Swiss, was championed by the French, billed as the figurehead, the driver, virtually the sole creator of this new movement. But like all great masters, from Leonardo to Frank Lloyd Wright, behind them and essential to their output, was a solid and talented team, many of who were equally or more capable.

Charlotte Perriand was born in Paris in 1903, her father a tailor, her mother a seamstress. Her creative talents were recognised from an early age; her school encouraged her to study furniture design at university. In the 1920s, alongside her degree, she also gained experience in the atelier of Maurice Dufrêne, designing furniture, fabrics and wallpaper for the Galeries Lafayette. In 1925, some of her words were selected to be a part of an exposition which gained her significant recognition.

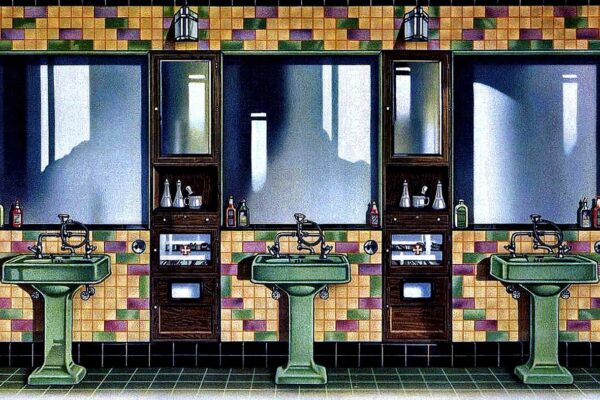

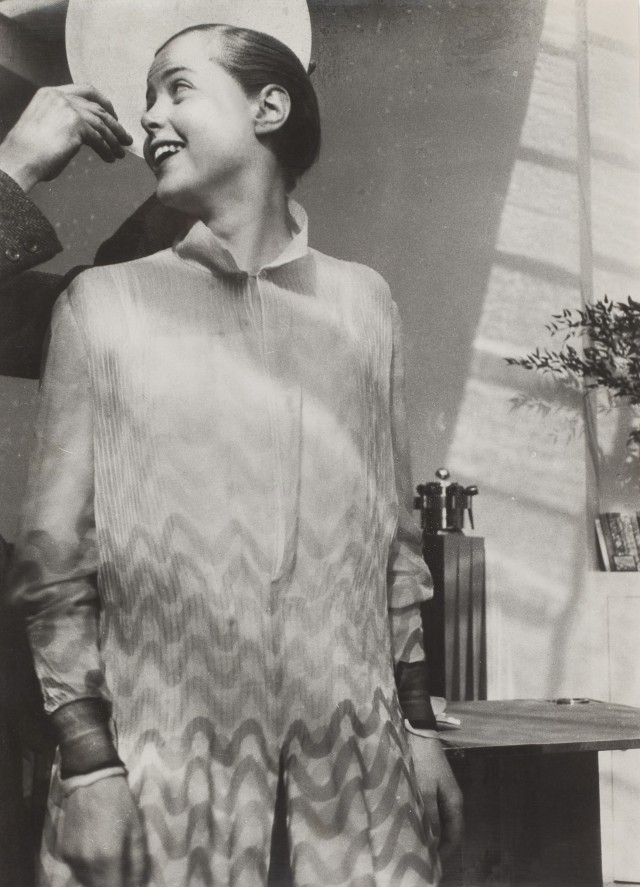

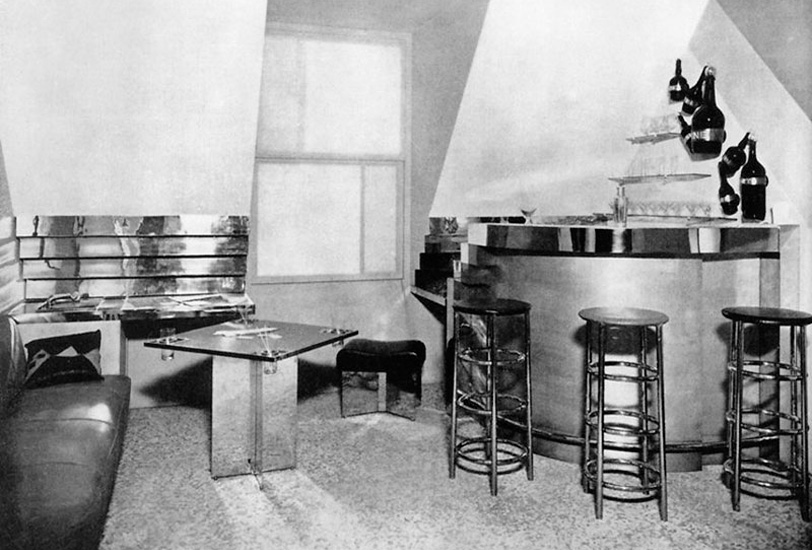

Perriand’s interior design career was launched when she remodelled her own apartment by installing a never-seen before modernist built-in bar constructed from aluminium, glass and chrome. She recreated this Bar sous le Toit (bar under the roof) two years later in 1927 at the Salon d’Automne, a contemporary art show that’s still held annually in Paris since 1903. Her approach was unique, radical and innovative, deliberately choosing shining industrial tubular metals, translucent sheet glass shelves contrasting with natural leathers. Noticed and praised by the press, Perriand was accepted as part of the new design wave, those who embraced the machine age, those who saw architecture and interior design not just as an industrial product, but as an expression of a new society. Not wanting to be a niche designer, nor a crafter of furniture for the rich, Charlotte Perriand sought to work with the likes of Le Corbusier, who was driving the design world to embrace grand social change by creating not just new residential spaces, but envisaged awe-inspiring new cities to improve the life of the masses.

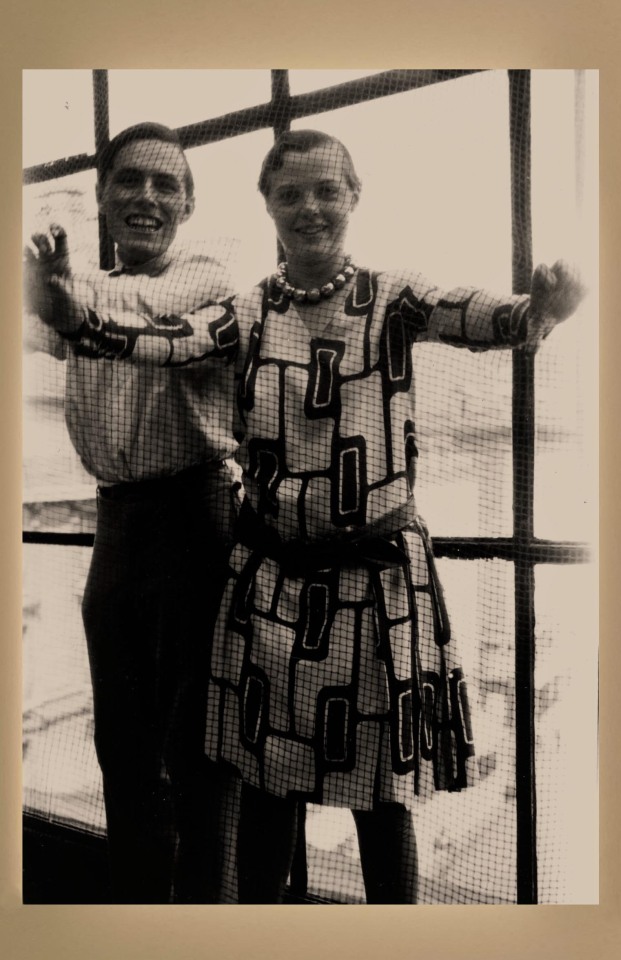

Charlotte had been inspired by the writings of Le Corbusier, however, when she finally made an approach to work at Le Corbusier’s studio in 1927, she was famously rebuffed by his sexist comments assuming that a woman was only good for her embroidery skills. The situation was soon remedied when his cousin, Pierre Jeanneret, took him to visit the Bar sous le Toit at the Salon d’Automne. Recognising her talent, he clearly spotted an opportunity to develop Charlotte Perriand’s ideas to supplement his own output. With Charlotte Perriand now on his team, as well as his own cousin Pierre Jeanneret, himself a visionary of modernist architecture and design, the trio formed a design spearhead within Le Corbusier’s studio.

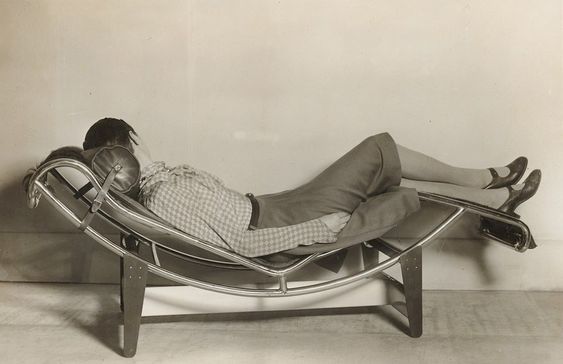

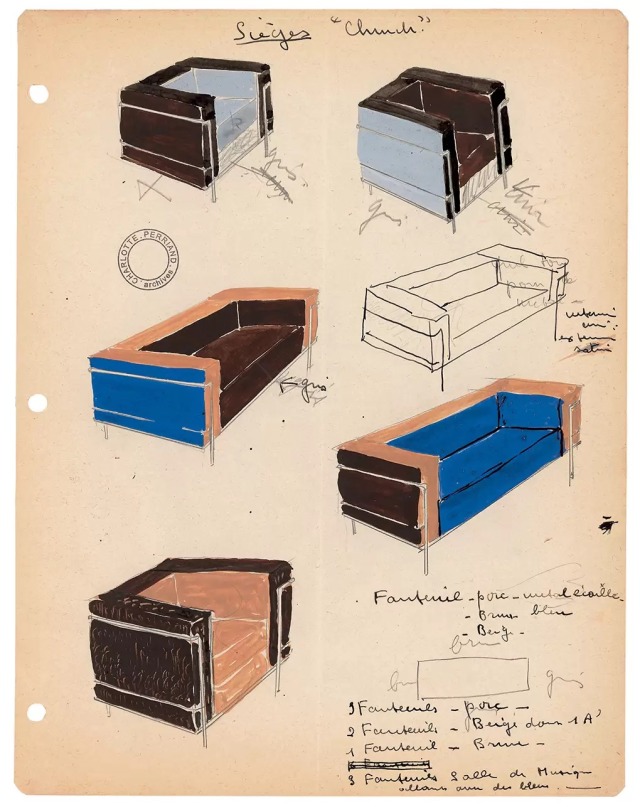

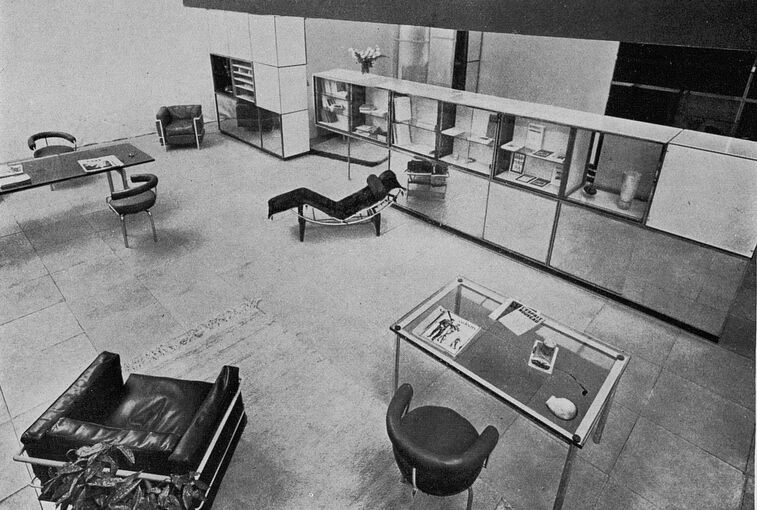

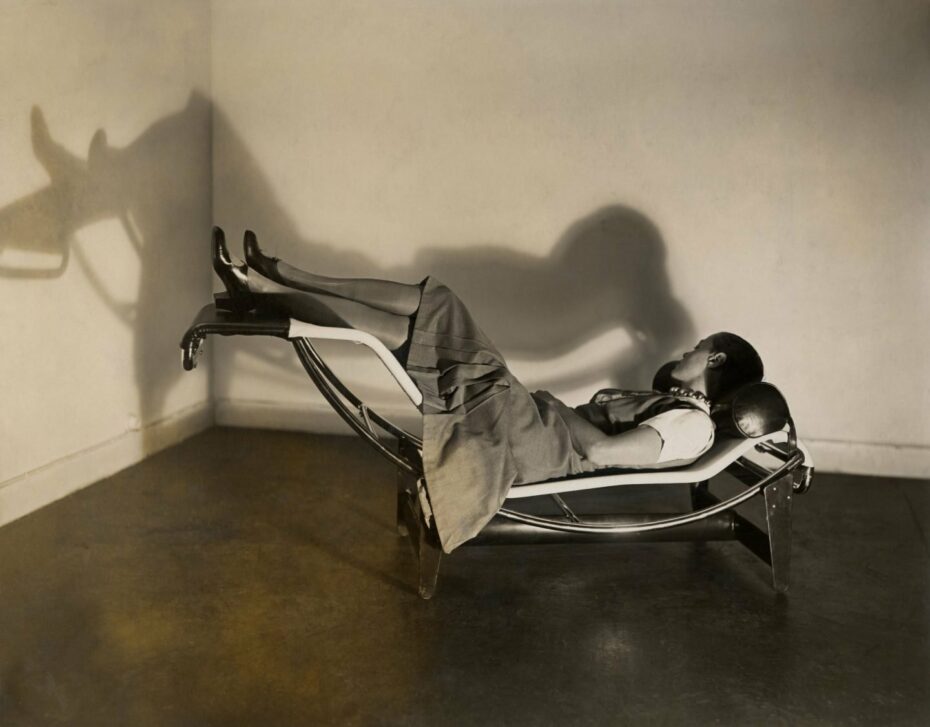

Charlotte was very much in charge of promoting the interior design output and had immediate success with the now legendary three chrome-plated tubular steel and leather chairs designed for two Le Corbusier’s projects, The Maison la Roche in Paris and a pavilion for Barbara and Henry Church. Billed as ‘Equipment for the Home’ each of the chairs design followed the International Style ethos that, just as a house was a machine for living in, so a chair was a machine for sitting in. One chair was upright for conversation, one relaxed for comfort and the third, the now famous chaise longue, for sleeping. Le Corbusier called it “très elegant” and put it into regular production.

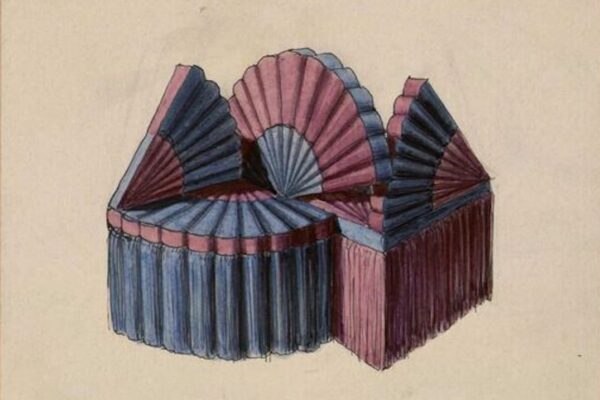

Into the 1930s and French society was moving to the left. Charlotte Perriand embraced the egalitarian movement and engaged with many leftist organizations. Her design moved away from the expensive industrialised metal engineering base to using cheaper and more sustainable materials that are more easily worked such as wood and cane.

After 10 years, Charlotte departed Le Corbusier’s studio, and while able to launch a successful career of her own, Corbusier remained the international ‘brand’ employed to create complete works from city masterplans to his own hand-painted murals on chapel walls. There was little room for shared credit and historians suggest if he’d had it his way, Le Corbusier would have taken the credit for some of her finest work. In many ways, he did, and only until recently is she stepping out of his shadow.

Sticking to her beliefs in a new egalitarian design philosophy, she started working with Jean Prouvé, a fabricator of industrial metal components, typically wall lamps, stair railings and small buildings. The outbreak of World War II, however, forced their hands to design military barracks and furnishings for temporary housing. Subsequently Jean Prouvé would go on to design mass-production lightweight steel frame demountable houses in 1944, clearly in anticipation of a new post-war Europe. In 1940, France had capitulated and Charlotte left France for Japan as an official advisor for industrial design to the Ministry of Trade and Industry. Attempting to return to Europe as the conflict spread to the Pacific, she was detained and forced into exile in Vietnam where she studied traditional woodwork and weaving. She took the time to understand Eastern design, most notably through The Book of Tea, an essay celebrating simplicity and humility, which she would refer to until the end of her life.

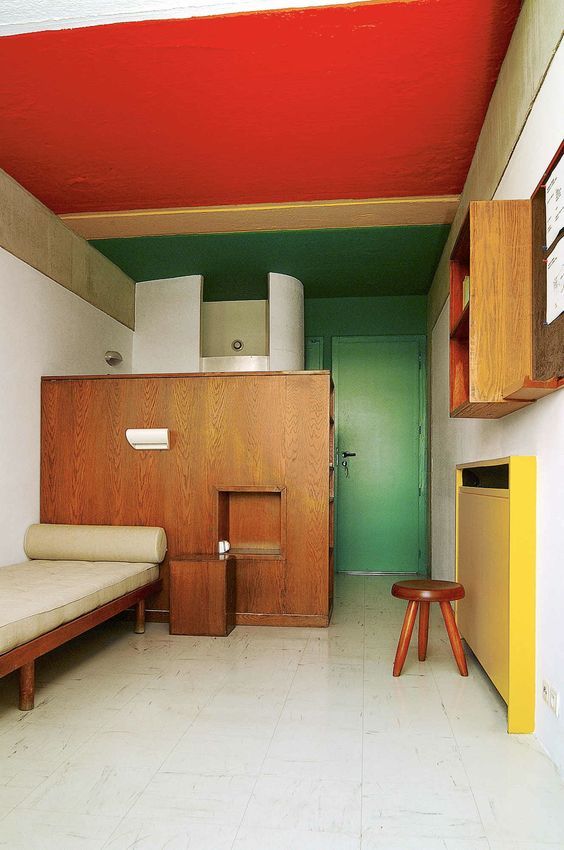

Charlotte Perriand returned to Paris in 1946 and by the 1950s, she was again working with Jean Prouvé and Le Corbusier, this time designing the interiors and kitchens for the famous and globally influential brutalist Unité d’habitation, a mass housing block in Marseille. She also designed her most signature designs, a free-form coffee table that has been imitated so many times, if you asked artificial intelligence to create an image of a standard modern coffee table, it would show you something very close to Perriand’s original design.

The 1960s through to the 1980s saw Charlotte Perriand finally able to deliver complete and innovative projects under her own name through a series of Ski lodges in Savoie. Les Arcs would become the biggest ski resort in the world with hundreds of residential units in a series of bold sculptural timber-clad buildings clinging to the mountain sides. Here she could combine the Corbusier functionalist concept of the machine for living with the Prouvé rationale for prefabricated industrial production and her love for natural materials. Aggressively sculptural, the repetitive timber room components form a saw-tooth skyline cascading down the snowy slopes. Inside, the simple planked woodwork is neat and rational, with the occasional crafted door-piece to add highlight and charm, very much in the Corbusier style that she pioneered in his studio.

Charlotte Perriand had a unique and prolific output, designing many internationally acclaimed buildings and particularly their internal furnishings. Many of her commissions were collaborations, rarely as the lead and thus never grabbed the headlines. Her greatest contribution and lasting legacies are perhaps the simple planked paneled & colored cabinetry and her chairs we all now take for granted in a world of anonymous industrial products. Looking back, Charlotte Perriand was a pioneer, and with numerous retrospective exhibitions of her work in the 1980s and 90s and after her death in 1999, is now recognized as one of the great innovators of her time.

Perriand believed that good functional design of living spaces would improve society. In 1981, she wrote in L’Art de Vivre, “The extension of the art of dwelling is the art of living — living in harmony with man’s deepest drives and with his adopted or fabricated environment.” Charlotte’s approach to design was deeply personal and contemplative, her preference was to visit sites alone. Perhaps it is was this unassuming spiritual approach to design that triumphed over a need for celebrity status that kept her out of the history books for so long.