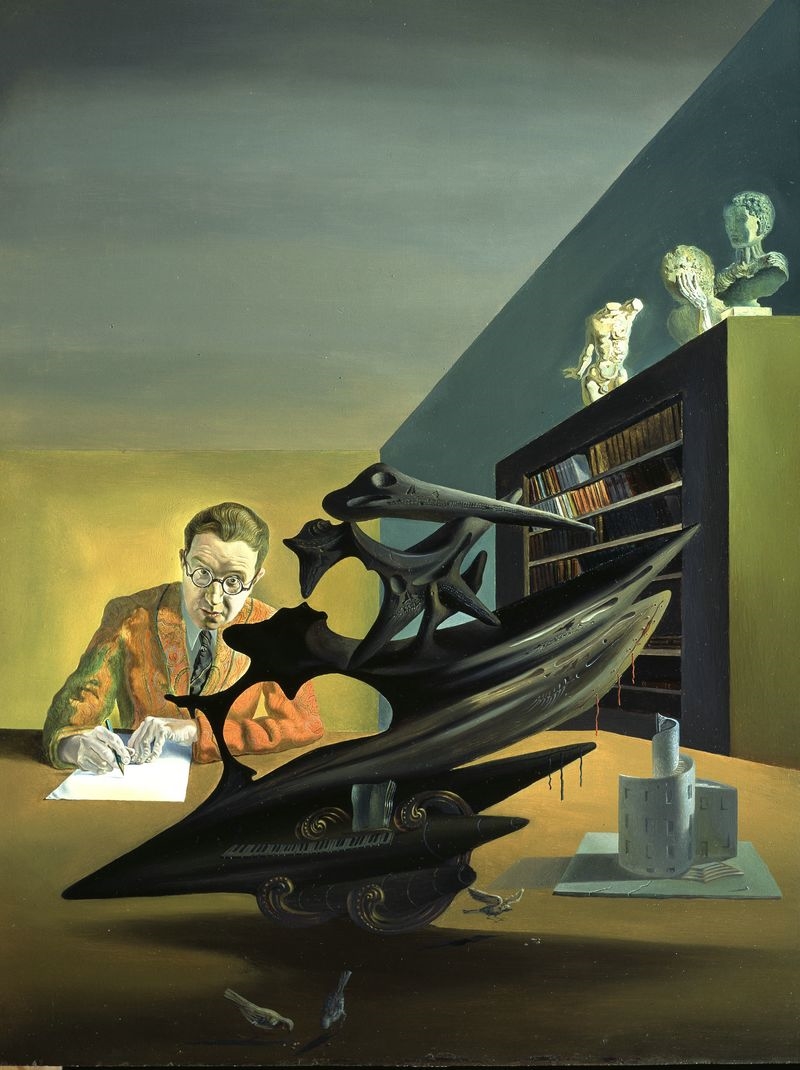

Let us take a look inside the classical grandeur and neo-romanticism that flows through the oeuvre of Emilio Terry. A maximalist from the school of more is most definitely more; Terry was an artist, architect, interior decorator, and darling of French society. Parisian born, he would mix in the elite circles of artists and aristocrats, Salvador Dali would immortalize him in oil paint and devotees of his Baroque decorative flair would covet his architectural creations. Widely unknown, and selective about where he bestowed his gift, his clientele would include Prince Rainier III of Monaco, the eccentric millionaire Carlos de Beistegui often referred to as the ‘The Count of Monte Cristo’, Stavros Niarchos a billionaire shipping tycoon and the who’s who of the mid 20th century swinging glitterati. Fabulous to those who could afford him and very expensive to those who couldn’t.

Emilio Terry would whimsically christen his aesthetic style as Louis XVII after the son of Louis XVI of France and Queen Marie Antoinette, who died as a boy in prison after the French Revolution. The Terry family lived in New York before returning to France and dwelling in the Château de Chenonceau that spans the river of the Loire Valley. A self-taught multi-disciplined artist who possessed an eye for the decorative sublime, taking inspiration from the fantastical lavishness of antiquity and the ornate surroundings of a privileged life, he would combine a surrealistic edge with an old form creating his unique aesthetic.

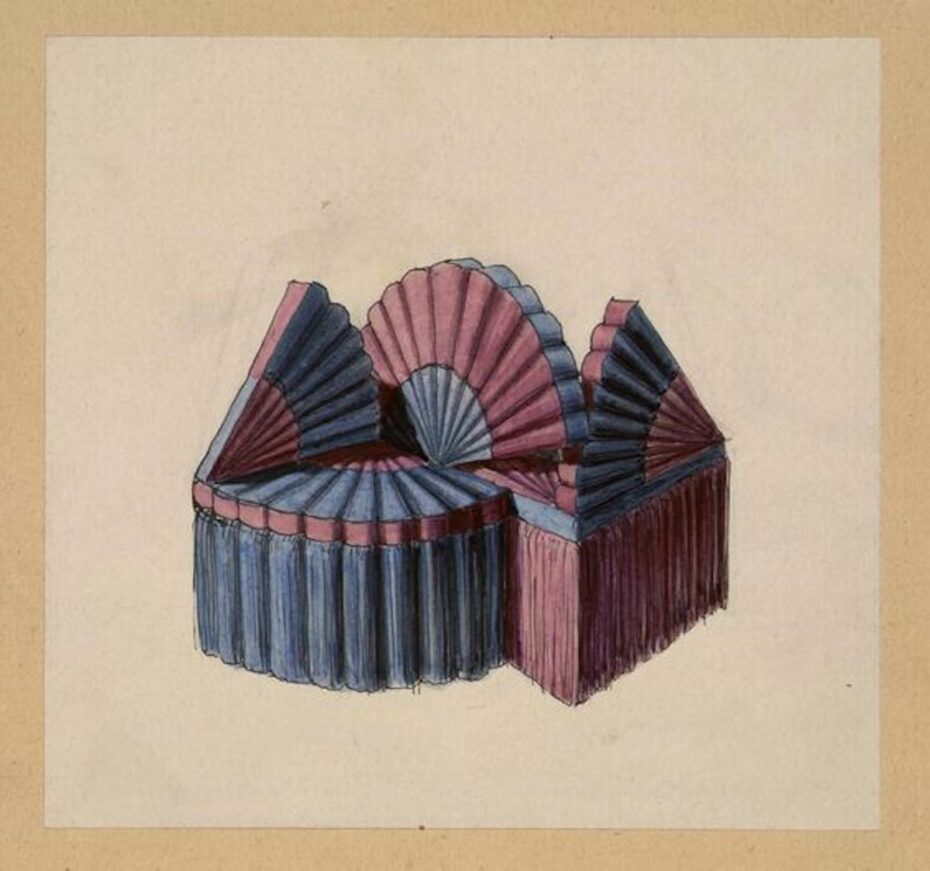

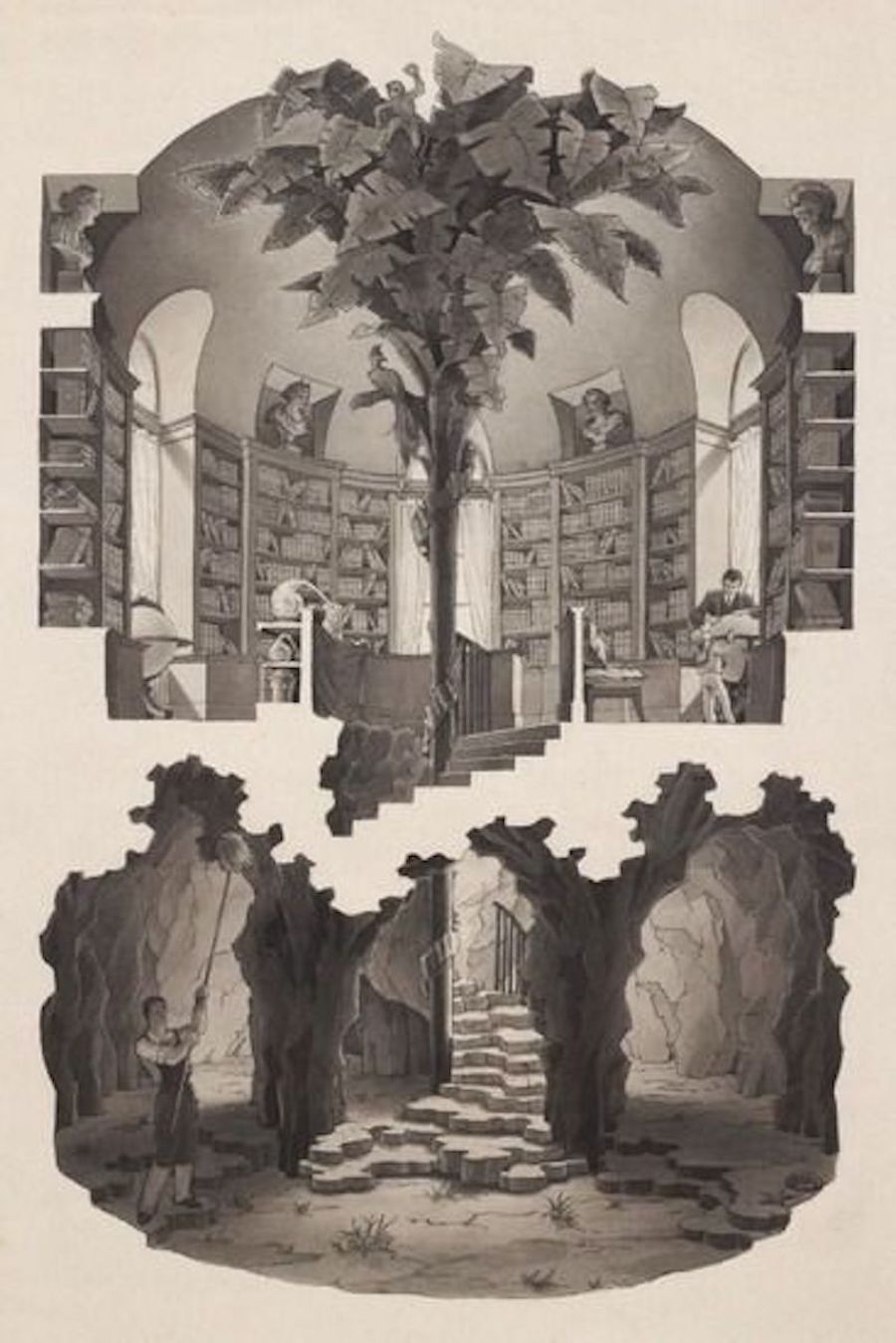

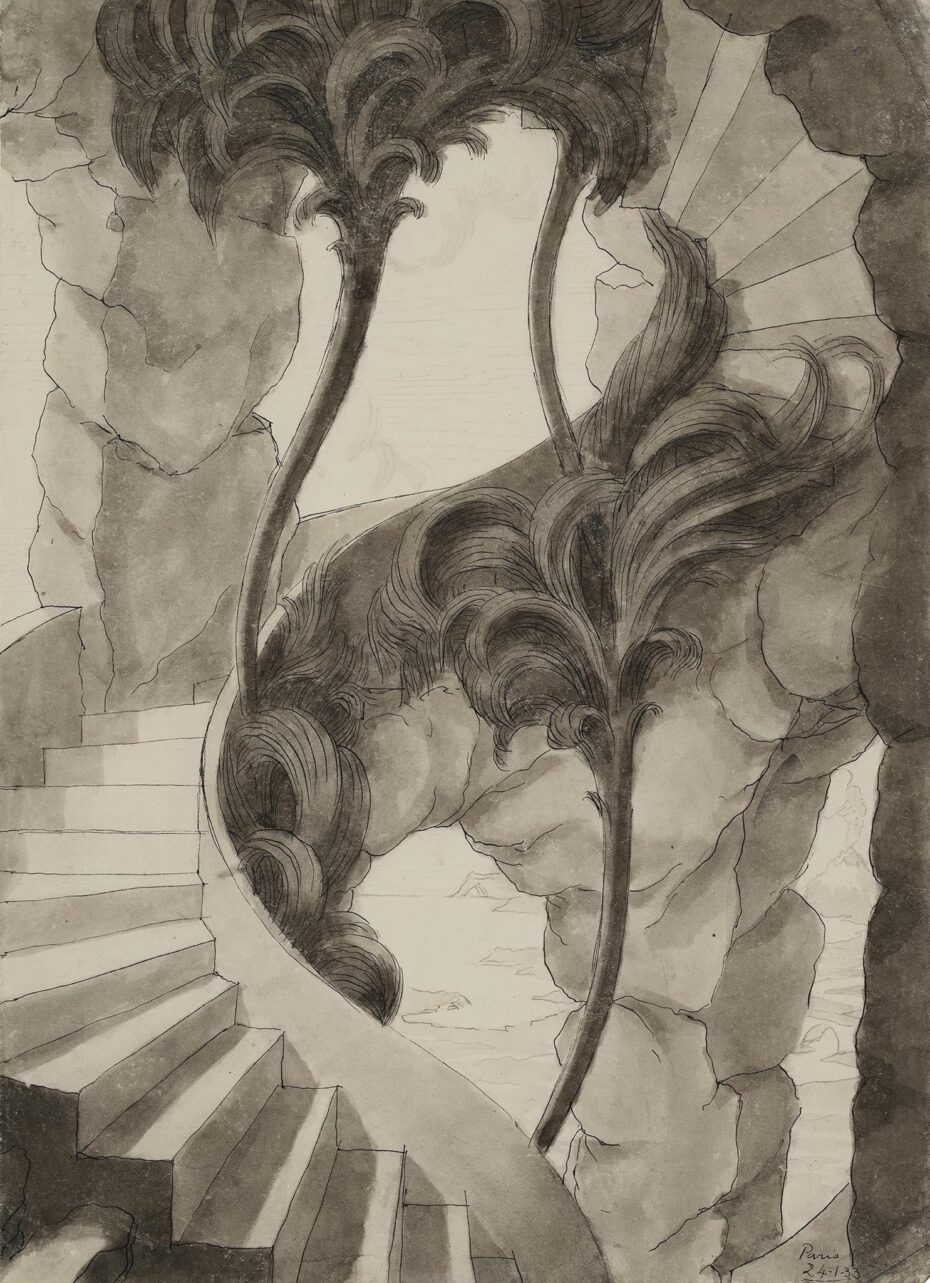

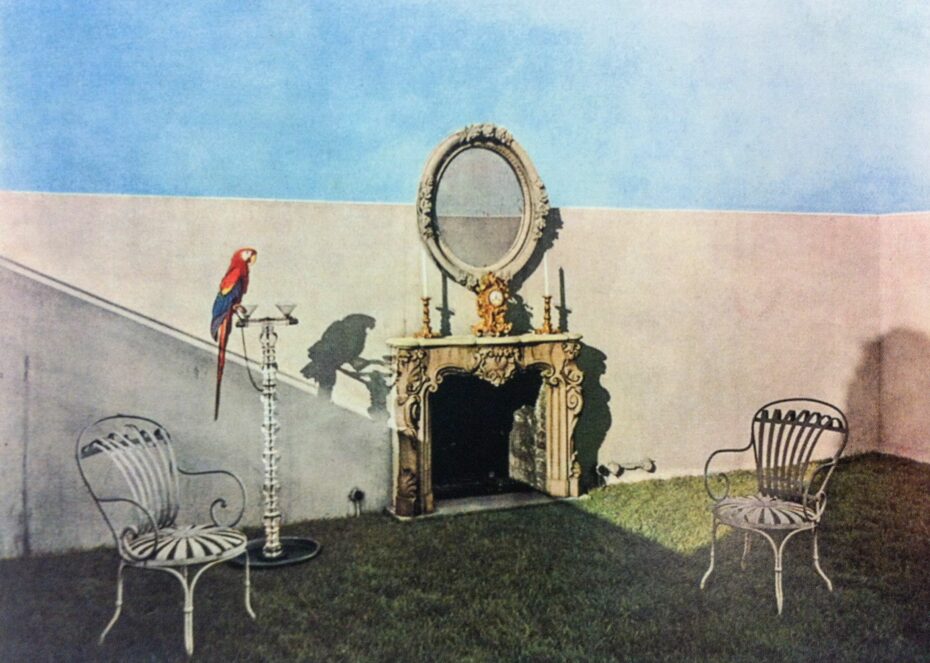

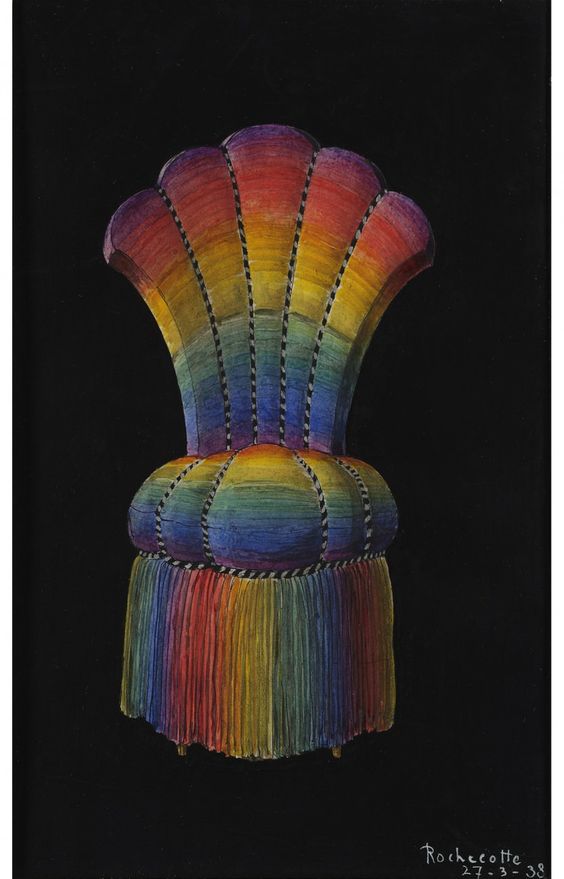

Terry’s influences can be seen in the work of French neoclassical architecture of Étienne-Louis Boullée and Claude-Nicolas Ledoux and by the 1930s the Surrealist movement was influencing modern culture and the work of Jean Cocteau, and Salvador Dali was threading its way into design and architecture. In 1933, Terry produced a conceptual design of a new house, which he labeled ‘en colimaçon’ or ‘Snail style’ a whorled experimentation into the surreal, it was never built but Terry had explored his vision of a building that is simply “a dream to be realised’. Tapestry, furniture, and objets d’art, would all have the gilded Neo Classical Louis XVII treatment, as Terry produced his ‘ideal for living’ fantasy. His refined take on just how one should dwell in splendour would attract the higher echelons of society, who all wanted the Emilio Terry touch.

When the Prince of Monaco, Rainier III wanted an apartment decorated for his new bride Princess Grace (Grace Kelly) it just had to be Terry. He would later design the interior for another princess, Princess Caroline, and her husband Ambassador Raymond Guest. The Parisian apartment would overlook the Parc Monceau and stay untouched for years until in 2013, when some of its furnishings went up for auction at Christie’s, giving a glimpse inside the sumptuous world that Terry had created.

When Edith Piaf needed a love nest for her and boxer Marcel Cerdan, Terry designed her a private mansion in the 20th arrondissement, with classical interior and circular living room where the singer would go on to write her chanson bleu after receiving the words in a séance in the house.

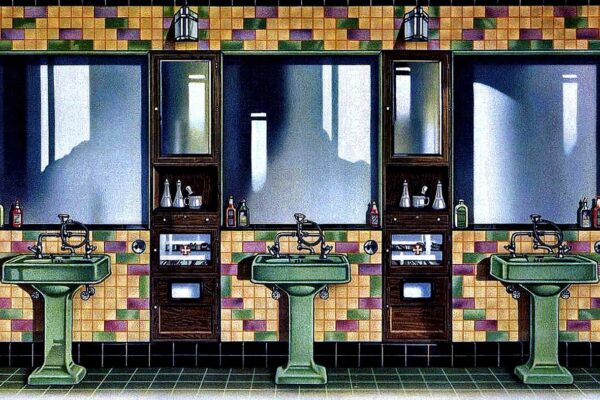

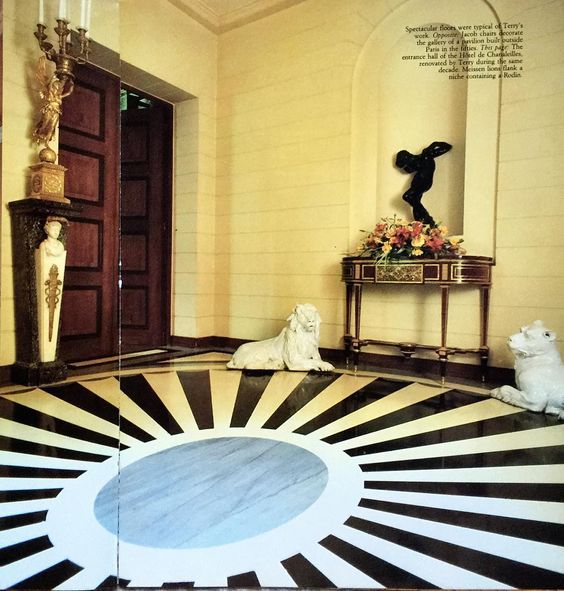

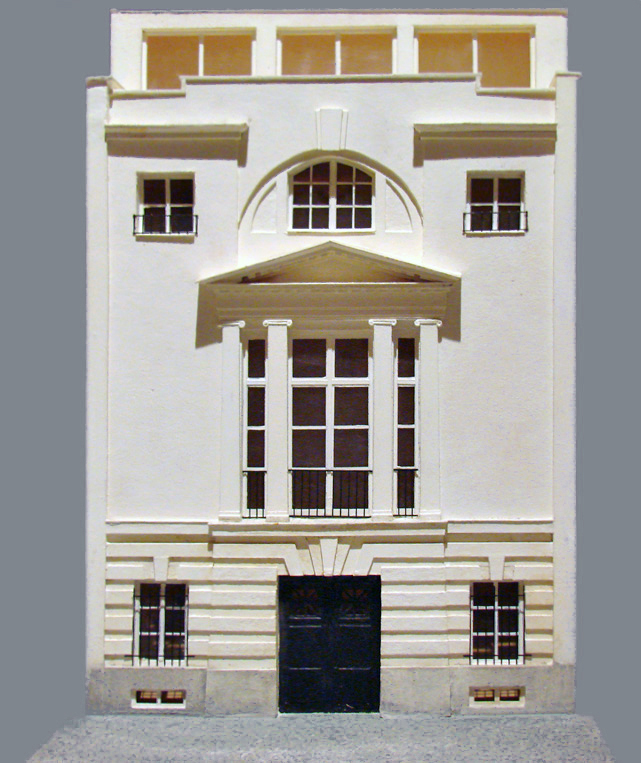

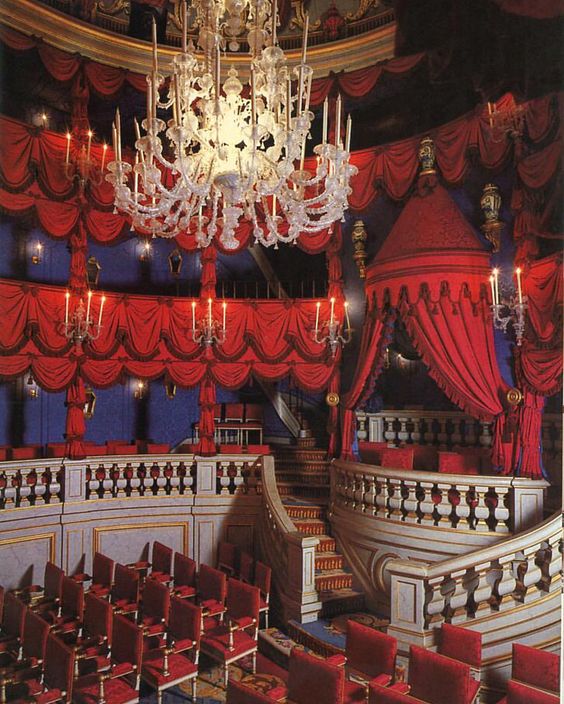

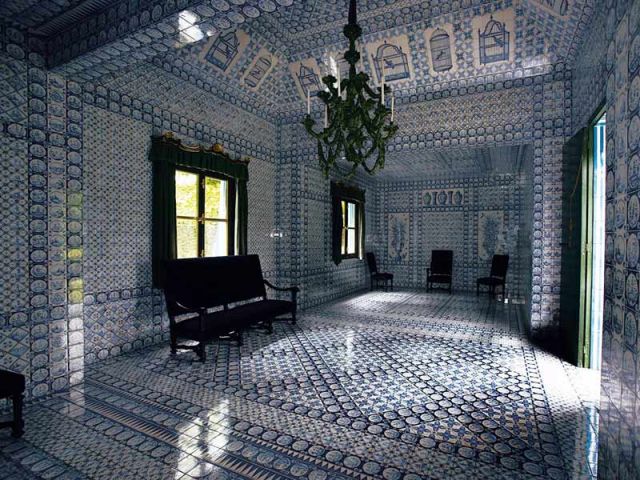

Probably the most celebrated of Terry’s work and his pièce de résistance is the reimagining of the Château de Groussay for Carlos de Beistegui (the chateau you should visit instead of Versailles). Located in Montfort-l’Amaury and built-in 1815, Terry would work on the new design from 1950 to 1970 in partnership with de Beistegui and Alexandre Serebriakoff, transforming the Château into a classical fantasy. The sumptuous interior held originally unique tapestries designed around the work of Goya, Ottoman-inspired tiled walls, and a 240-seated theatre decorated with lavishly vivid fabrics. There were chandeliers galore, Louis XV armchairs, and empire beds.

On the grounds, Terry produced an exquisite folly of classical proportions, complete with royal guards’ tents, a Chinese Pagoda, an exotic observatory, and a labyrinth. Today the grounds are classified by the French government as one of the Remarkable Gardens of France.

A lot of Terry’s oeuvre can be hard to pin down as his work was so exquisitely favoured towards his coterie, hidden behind those classical dimensions and Parisian facades. His work lives in spaces he chose to display his fantastical grandeur, the materials and colours he picked, the furniture he designed, the textures he played with, and the lines he drew. His sketches and designs played into a world of his creation, a classical time that never was and only existed in his compositions and the few places sprinkled with touches of Louis XVII, the lost prince, and his extravagant style. Terry would continue to work for a selected few until his death in 1969.