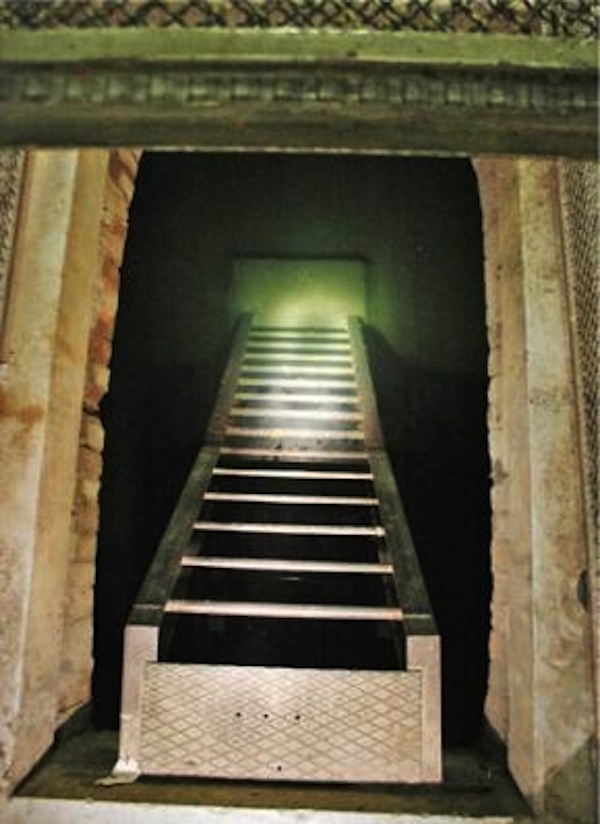

What if I told you there is a lake under the Paris Opera House, just like in The Phantom of the Opera? Down, down, down, deep underneath the Garnier Opera in a dingy room with a square-shaped hole in the middle, I found it. Resting in the hole was a ladder that seemed to be descending into nowhere. “What’s this?” I asked. “That,” answered my guide with a twinkle in her eye, “is the lake.”

(c) 20 minutes

As in THE lake from the The Phantom of the Opera?

I didn’t know it when my tour started, but the famous fable was set right where I was standing. As we glided through the sprawling staircases and hidden doors in my favorite Parisian monument of all time, it became clear that the phantom was much more than a fairytale…

Our guide pointed out the very chandelier that, in the story, drops into the audience and led us into lodge number 5, the phantom’s private balcony hideout. The place was so riddled with remnants of the ghost that I had a feeling a little research would pull up some interesting surprises.

I had no idea of the revelations I was in for…

You see, The Phantom of the Opera was written by Gaston Leroux, a French journalist and opera critic. Originally published in installments for the newspaper Le Gaulois in 1909, the story begins: “The Phantom of the Opera did exist.”

The novel is saturated with people that really lived, events that actually happened and places you can still visit today. Few are aware of the fact behind the fiction; the book isn’t even considered one of Leroux’s great works in France.

So I decided to get in touch with Mireille Ribiere, the woman who researched and re-translated every corner of the legend for Penguin Classics, feeling that other versions didn’t do justice to the author’s relationship with the Opera House. She confirmed that Leroux’s descriptions of the Palais Garnier and what transpired within its walls are so in-depth and accurate, it’s no wonder that people still question if the phantom was real a century later.

So was it?

The Phantom and Christine from the 1926 silent film.

Clue No 1: The Lake

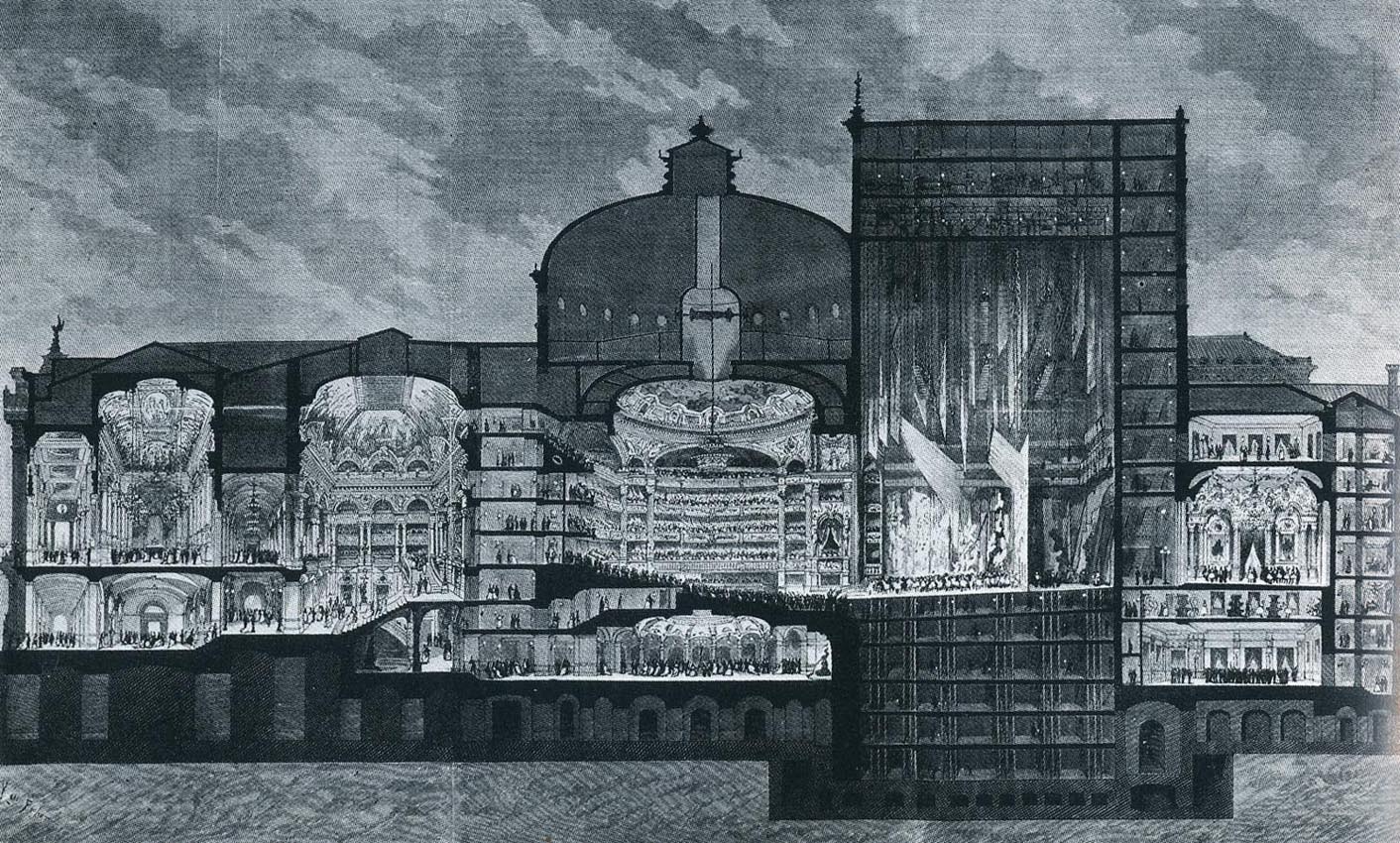

Charles Garnier, architect of the eponymous Opera House, ran into a slight problem while digging its foundation. They had hit an arm of the Seine hidden below ground and no matter how hard they tried to pump out the water it kept rushing back. Rather than move location entirely, Garnier adjusted his drafts to control the water in cisterns, creating a sort of “artificial lake.”

(c) Emmanuel Donfut / (c)Plongeur.com

While it looks nothing like the famous romantic lagoon in the musical, the Opera staff enjoys feeding the resident fish and the Paris Fire Department goes diving there from time to time.

Clue No 2: The Falling Chandelier

“The chandelier had crashed upon the head of a poor woman who had come to the opera that evening for the very first time in her life, and killed her instantly. She was the concierge…”

– Gaston Leroux, The Phantom of the Opera

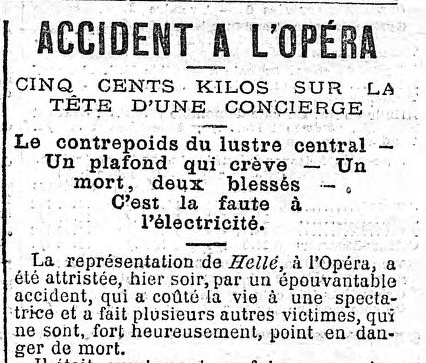

In the May 21st, 1896 issue of Le Matin, a newspaper where Gaston Leroux was moonlighting as the senior courtroom reporter, a headline read: “Five hundred kilos on a concierge’s head!”

In reality, one of the counterweights of the chandelier weighing less than ten kilos fell into the audience—but killed one woman. She was Madame Chomette, a concierge.

(c) Phantastically Beastly Reviews

Spooked yet? There’s more…

Clue No 3: An Architect who lived under the Opera House with the same name as the Phantom?

During my research, I was put in touch with a literary professor by the name of Isabelle Casta, who has extensively studied Gaston Leroux and his novel. According to Casta, Monsieur Leroux heard a strange rumour during a visit to the Opera House in 1908 that one of Garnier’s architects, named Eric, had asked to live underneath the incredible structure … and hadn’t been seen since.

It’s no coincidence that Leroux’s phantom is a man named ‘Erik’ who was a contractor for Garnier.

“But when he found himself in the basement of the vast playhouse, his artistic, illusionist bent gained the upper hand once more… he dreamed of creating for himself a secret retreat, where he could forever hide his monstrous appearance from the world.”

–Gaston Leroux, The Phantom of the Opera

Clue No 4: The Real Christine

“Yet nothing compared to the unearthly power of her singing in the prison scene and the final trio of Faust.”

–Gaston Leroux, The Phantom of the Opera

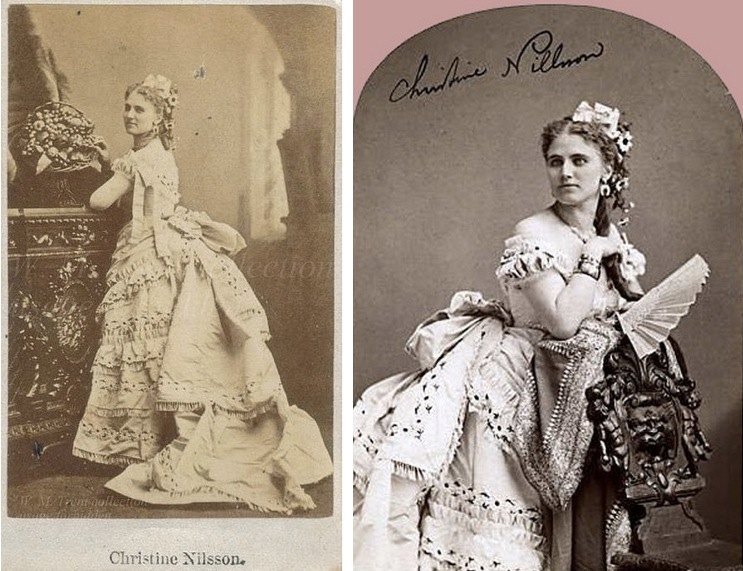

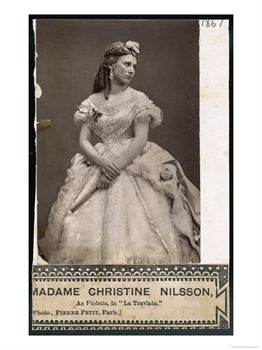

The fictional ingénue of our novel might be named Christine Daaé, but she certainly resembles a real-life soprano Christine Nilsson, who was famous for her performances in the operas Hamlet and Faust.

Nielsson and Daaé have much in common: both were both Swedish with blonde hair and blue eyes. Both were the daughters of poor men, forced to leave their homes at a young age and eventually taken in by a character named Valerius in Gothenburg. Most importantly, both eventually ended up in Paris—although Nilsson never sang at the Garnier Opera, mysteriously cancelling her performance before the Opera’s inauguration at the last minute.

Nielsson and Daaé have much in common: both were both Swedish with blonde hair and blue eyes. Both were the daughters of poor men, forced to leave their homes at a young age and eventually taken in by a character named Valerius in Gothenburg. Most importantly, both eventually ended up in Paris—although Nilsson never sang at the Garnier Opera, mysteriously cancelling her performance before the Opera’s inauguration at the last minute.

Clue No 5: The Buried Phonographic Records

Captured in this photograph taken on Christmas’ Eve, 1907, twenty-four phonographic records of the era’s greatest opera singers were sealed in vaults hidden deep underneath the Paris opera. They remained unopened for one hundred years.

“Some of you may remember that latterly workmen, digging in the vaults of the Opera House where phonographic recordings of singers’ performances were to be buried, came upon a corpse; I had immediate proof that this was the body of the Phantom of the Opera.”

–Gaston Leroux, The Phantom of the Opera

Forgotten underground, the time capsule was discovered in 1989 by workmen fixing the Opera’s ventilation system and were finally opened in 2008. However no real evidence has been found of a body exhumed during the records’ burial as described in Leroux’s novel.

(Nonetheless, you can buy what might have been the real soundtrack to the Phantom of the Opera here).

(c) Bibliotheque Nationale de France

Clue No 6: Corpses of the Commune

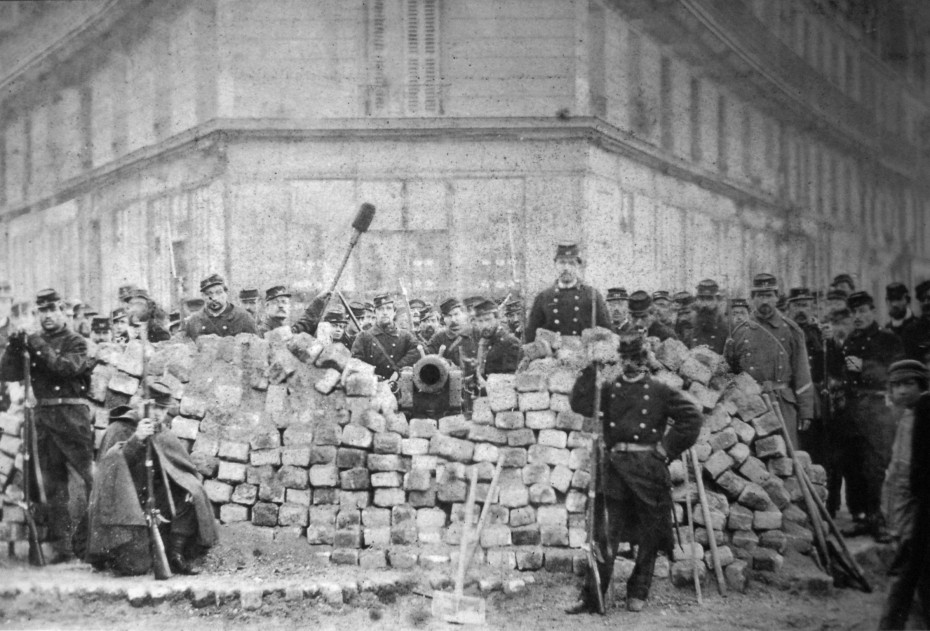

The book begins with the narrator (who signs his name G.L., like Gaston Leroux) arguing that the body found during the phonographic records’ burial was misidentified as a “victim of the Commune” and is, in fact, that of the phantom. Traces of this “Commune” show up all over the book… but what is it referring to?

The Commune was a revolutionary utopian government that seized Paris for two months in 1871. In the novel, the Commune used the Opera for everything from housing its dungeon in the basement to launching balloons from the roof. It is true that while under construction, the Opera House served as a shelter and storehouse for food and ammunition during the Prussian siege of Paris, which ended two months before the reign of the Commune. Weirder still are the corpses that kept turning up at new urban development sites around the time that Leroux was writing The Phantom of the Opera. As Jann Matlock writes in the introduction to Mireille’s translation, “It would not have been the least bit surprising… for the Opéra to shield the body of one of those ‘wretches’ massacred… between 21 and 28 May 1871, when an estimated 25,000 Parisians met their deaths.”

“You think you have been following me, you great clod, whereas in fact I have been following you; and you cannot conceal anything from me. The Communards’ passage is mine and mine alone.” –

– (Erik the Phantom) Gaston Leroux, The Phantom of the Opera

Clue No 7: Unknown Passageways into the Opera?

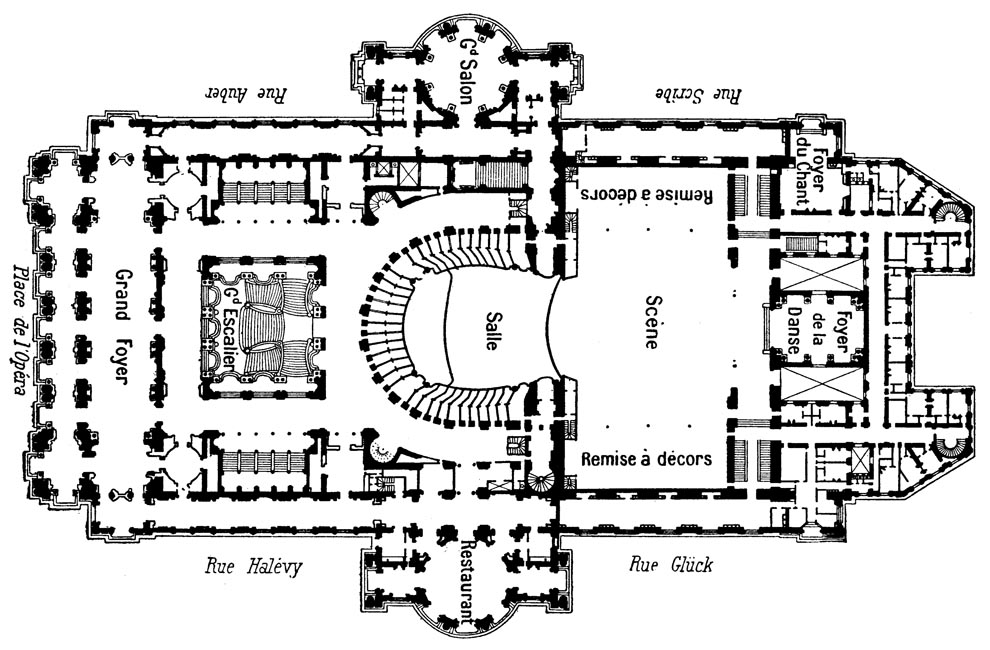

“…found on the shore of the underground lake that lies beneath the Paris Opera House where it boarders the rue Scribe.”

Gaston Leroux, The Phantom of the Opera

In the top right-hand corner of the above blueprint you can see where the Opera House follows rue Scribe. The phantom uses an entrance found on this street to access the depths of the Opera House. The underground system in Paris is so vast and complex, it’s completely possible that unknown passages leading into the Opera’s cellars from the outside world exist. Jann Matlock even states that, “surely, in a building that had 1,942 keys, there were people who knew how to get down to these cellars without the permission of the authorities. Perhaps there were even those who made these undergrounds their regular haunt.”

So, was the Garnier Opera House really once haunted?

Mireille Ribiere, whose translation of the book was released by Penguin in 2009 and mentored my research for this article, told me that the phantom is most certainly made-up. I protested, citing that Leroux himself insisted that the phantom was real, openly proclaiming it after the film version came out in 1926. The man even vowed it on his death bed!

Mireille patiently explained to me that Leroux was a flamboyant, larger-than-life character who reacted as anyone would, with all of Hollywood asking if the phantom was real. “If your make-believe has been so successful that people ask the question, you are not going to destroy the illusion. If people wanted to believe that he had existed, he was not going to disappoint them. That’s how I see it,” Mireille resolved in our final exchange. “But having said that, perhaps he really believed it.”

For Mireille and other scholars, Leroux was a groundbreaking journalist and master of the detective novel who wove fact and fiction together so intricately that a ghost became tangible.

I know that Mireille is probably right, but when you’re descending into never-ending labyrinth of the subterranean Opera, anything seems possible.

The phantom of the Opera is there, at least inside my mind.

To experience this mythical institution for yourself, book a guided tour. Paris too far away? Or take a virtual tour.

* Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes and factual information come from Mireille Ribiere’s translation of Gaston Leroux’s The Phantom of the Opera for Penguin Classics (available from Amazon).

About this contributor:

Rozena Crossman moved to Paris on a whim in July 2011. A professional adventurer, she is relentlessly improving her linguistics in both English and French at the Graduate School of Life.

Rozena Crossman moved to Paris on a whim in July 2011. A professional adventurer, she is relentlessly improving her linguistics in both English and French at the Graduate School of Life.