Almost a decade ago, Indy Srinath made herself a pretty ambitious promise. “It was like having a sudden awakening,” she tells Messy Nessy Chic about her decision to learn the name of every single plant she discovered, “where you feel like you’ve been living with a crowd of people who serve you your entire life, but never made the effort to learn any of their names.” She hasn’t stopped learning since. Today, Srinath has blossomed into a true Renaissance woman of all things environmental. She’s a passionate ethnomycologist (aka mushroom whisperer), sustainable farmer, and longtime fosterer of gardens in Black and brown communities in the US; at present, she manages an urban farm on a rooftop of Skid Row in Los Angeles, California. Above all, Srinath has managed to make all of these interests feel so accessible and magical through her Instagram, where you can tag along on her farming and foraging adventures. What did it take for her, as both a former-novice and a woman of colour, to succeed in her fields? She opened up to Messy Nessy about why it’s so important to foster green spaces, careers and resources for Brown and Black communities…

If you love science, but are pretty bad at it (enter all of team MNC), there’s nothing more fascinating than asking a forager to define “foraging.” At its simplest, it’s the act of finding useful, natural elements – usually, for eating – that requires equal parts science savvy, and a poetic back-to-the-land ethos. “I personally define foraging as the meditation of connecting with plants and fungi,” writes Srinath, who was also inspired by Walt Whitman and Jack Kerouac to first learn the botanical names of plants, “[and] in a way that benefits both parties. It might include picking mushrooms to consume, while carrying and spreading their spores throughout the forest. Or harvesting over ripe fruit to allow a tree to put its energy into growing leaves and stronger root systems. Sometimes it’s picking herbs that grow in large quantities and turning them into medicine.” The most important part of what makes that relationship healthy, she says, is a sense of “reciprocity, respect, and reverence for the land.”

In the past few years, Millennials in particular seem to be revering the land. Pining for it, even. Living in the big city, it feels like every six months or so, another friend moves upstate to live out a pastoral existence with their quirky cat. Social media, too, has been overflowing with #CabinPorn and #Cottagecore (exactly what it sounds like) content for years, touting images of berry picking, mushroom hunting, and bottle feeding baby animals. For some, scrolling through that lifestyle aesthetic is salve enough. For others, the truly educational platforms from influencers like Srinath become an accessible first steps towards cleaner living.

“A wind of change is ripping through,” reported Financial Times in 2018, “For decades, consumers trusted [big] brands they knew and convenience food was a novelty. No longer.” According to Euromonitor and Pew Research, millennials are in general more health-conscious than their parents were at the same age in matters of plastic waste, alcohol consumption, and transparency about brands’ environmental impacts.

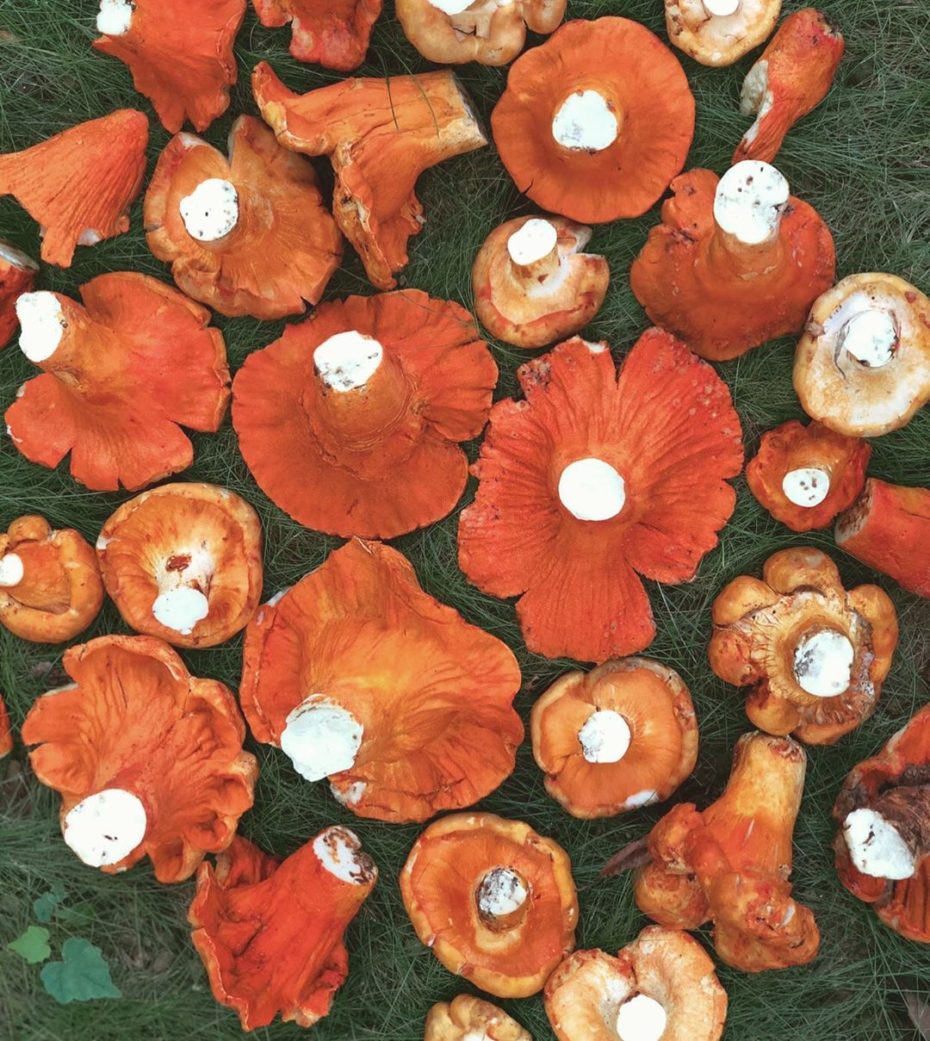

“I think a lot of people think of foraging as some hippie activity that you do when you live on a commune and wear buckskin clothes and a ton of patchouli,” says Srinath, “For me, it’s the opposite. I think that, conversely, it’s a very modern approach to fresh food […] I believe mushrooms are making a comeback with millennials because honestly they just look really cool and are capable of doing really incredible things for the body. Medicinal mushrooms can help with a lot of physical and psychological conditions with absolutely none of the harmful side effects of pharmaceuticals.”

You can also get closer, she says, “to the source of some of the most highly considered epicurean delights like truffle mushrooms. You can forage to create some incredibly high quality dishes.” One of her dreamiest finds was a bunch of Hypomyces Lactifluorum, or Lobster Mushroom. “I had done a lot of research as to where I might find it,” she says, “and it paid off really well. It’s such a strikingly beautiful find.”

Therein lies the thrill of the hunt, which Srinath describes as “50% wandering around in the woods and 50% talking and laughing, sipping beer and having a fun time exploring.” Which isn’t to say this woman doesn’t majorly do her research before driving (sometimes) up to eight hours to forage. “I might walk into the woods and see a certain type of pine tree growing and think to myself, ‘Okay, this pine tree is growing here so it’s telling me that the forest floor is going to be mostly pine needles. What is that telling me about the soil? Pine needles have a pH of about 3.2 when they drop from a tree. Trilliums (a type of flowering ephemeral) love acidic soil, so I might find those in that area.’”

Building a career in such “green” fields hasn’t been easy. “I began learning about plant identification and foraging in North Carolina in predominantly white spaces. I spent my early adulthood working on various farms that practiced different agriculture techniques,” says Srinath, who identifies as a woman of colour. “I didn’t see a lot of representation of people of color in my field of work, which led me to begin creating educational spaces for brown and Black folks interested in farming.”

“Growing up in North Carolina,” says Srinath, “I knew that it can feel unsafe wandering around in rural, and woodland areas. There is a huge culture of aggressive property ownership. As a person of color it is even more prudent to make sure you didn’t accidentally wander onto other peoples land. It’s a shoot first, ask questions later culture. I learned a lot of things the hard way.”

The reality is that we can’t talk about the history of green access, and land ownership in the US without addressing some deeply racist roots. As schoolchildren, we’re told that post-slavery reparations were neatly tied up in the government promise of “40 Acres and a Mule.” What we’re not taught, is that this plan was actually carefully drawn out by a group of Black ministers and failed to go into effect. As Henry Louis Gates, Jr. wrote for The Root, “Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s successor and a sympathizer with the South, overturned the Order in the fall of 1865, and, ‘returned the land along the South Carolina, Georgia and Florida coasts to the planters who had originally owned it’ — to the very people who had declared war on the United States of America,” as Barton Myers concludes.

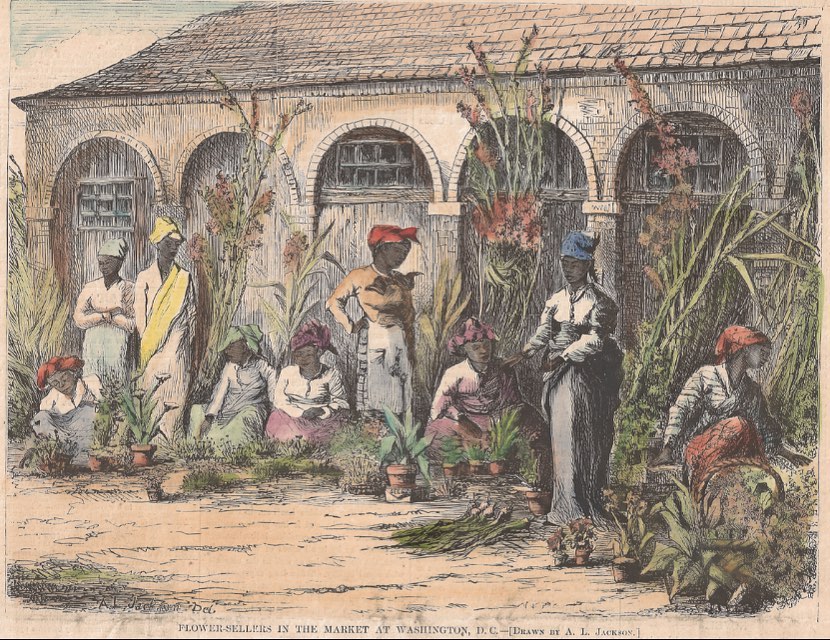

At the same time, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, continued to till the crops that fed the country, to plant and sell the flowers that decorate its homes. Consider the legendary Black flower sellers of Washington D.C. “I had never seen a picture of what they looked like – until now!” writes horticultural storyteller Abra Lee in a recent post, “Today we call these women (and men) Flower Farmers. Type ‘Flower Farmer’ into Google images, and tell me how many Black women you see. This picture is from June, 1870 (spoiler alert y’all – we ain’t new to this!).”

Srinath’s words echo that admiration, while calling for consistent, sincere inclusionary strides to be made in green jobs and hobbies. “How hard is it to feature one brown face [in a campaign]? If this work is deemed essential during the time of covid-19, but isn’t honored or respected during the rest of the year, then there is something gravely wrong with the way we view farm work. I quickly learned you can’t just manifest diverse spaces. You can’t just say, ‘Hey, let’s bring some brown people on this hike.’ You have to seek out teachers that are people of color, which I had the honor of learning from in a few spaces. You have to learn what the barriers are. A lot of times it was in advertising. I would see fliers for skill shares and plant identification hikes that had no diversity, it would just include a picture of white folks with baskets and knives—thats not a very inviting picture to people of color.”

At the end of the day, we aren’t simply what we manifest. We’re defined by what we buy – or don’t. “I feel like food sovereignty is key to living a healthful lifestyle,” she says, “Controlling and knowing what you consume, from the media and books you read to the medicines you ingest to the food that you eat.” In that light, says Srinath, teaching someone to grow or forage transcends the pastime of a hobby. It blossoms into a form of radical activism.

Learn more about Indy Srinath’s amazing work on her Instagram, and donate if you can to the Linktree in her bio to help fund her research, community work, and dream of travelling to South East Africa to “learn from and document the ways in which folks forage for and grow edible and medicinal mushrooms.”