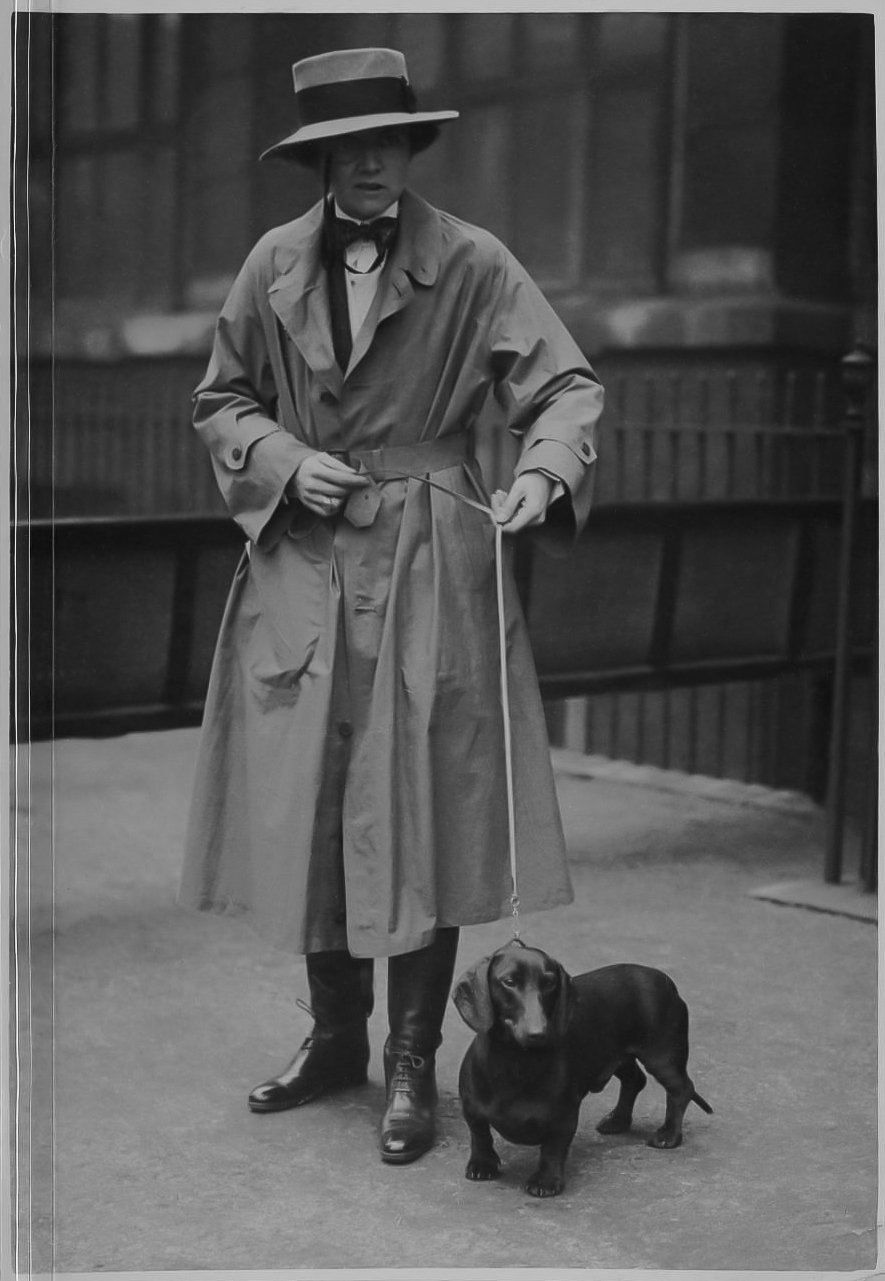

Rest assured, the roots of fashion have never really been straight. Weaving in and out of contemporary culture, lesbians have been creating sapphic waves of influence on the mainstream style codes for generations; quietly, but surely. You know Una “Lady Troubridge” Vincenzo, even if you don’t think you do; her unmistakably sleek bob, the tux, the monocle. The striking avant-garde aristocrat was a favourite target of early 20th century society magazines that fed off the gossip of the eccentric English elite. In fact, Lady Troubridge feels like just the sort of inspiration one might need, should a prequel of this year’s hugely popular film, Saltburn, ever materialise.

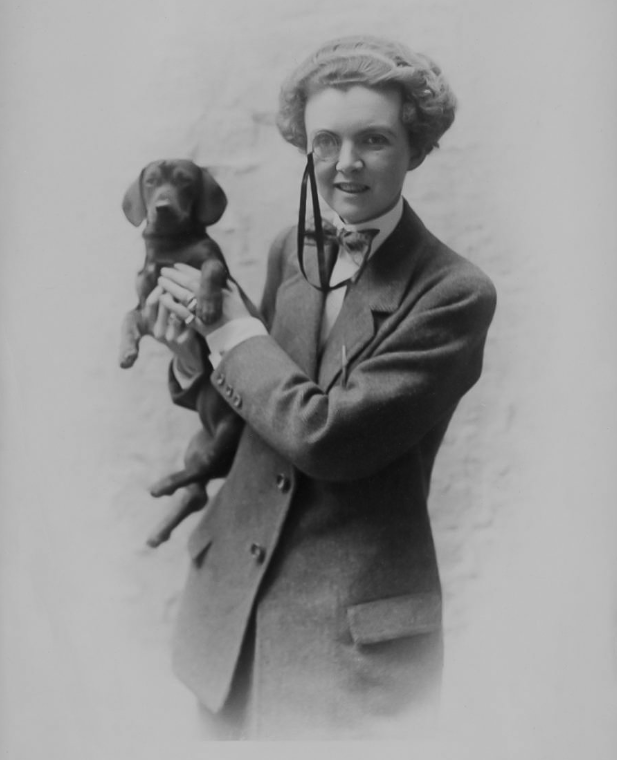

Much of what we know about Una today are from the stories published is in relation to her coupling with Marguerite Antonia Radclyffe Hall, who made a name for herself with groundbreaking work in lesbian literature. In adulthood, Hall often went by the name John, rather than Marguerite. Although the union typically took the spotlight, Lady Troubridge herself was known for her work as a sculptor, translator and patron of the arts. Most notably, she was a successful translator and introduced the French writer Colette to English readers.

As a young woman, Una married Admiral Sir Ernest Troubridge, a man a quarter of a century her senior, who propelled her into the upper echelons of British society. She gave birth to a daughter, but the Admiral was often away at sea, and in 1915, she was introduced to the charismatic Radclyffe Hall, a-then longtime lover of Una’s cousin, Mabel Batten. They fell in love hard and fast, breaking hearts along the way. Mabel died just a year later, leaving Una wracked with guilt and seeking forgiveness from her cousin beyond the grave, through mediums and séances.

Meanwhile, the Admiral appeared to tolerate his wife’s close relationship with Hall for several years, until an argument prompted a separation in 1919 which quickly became public news and fodder for the tabloids.

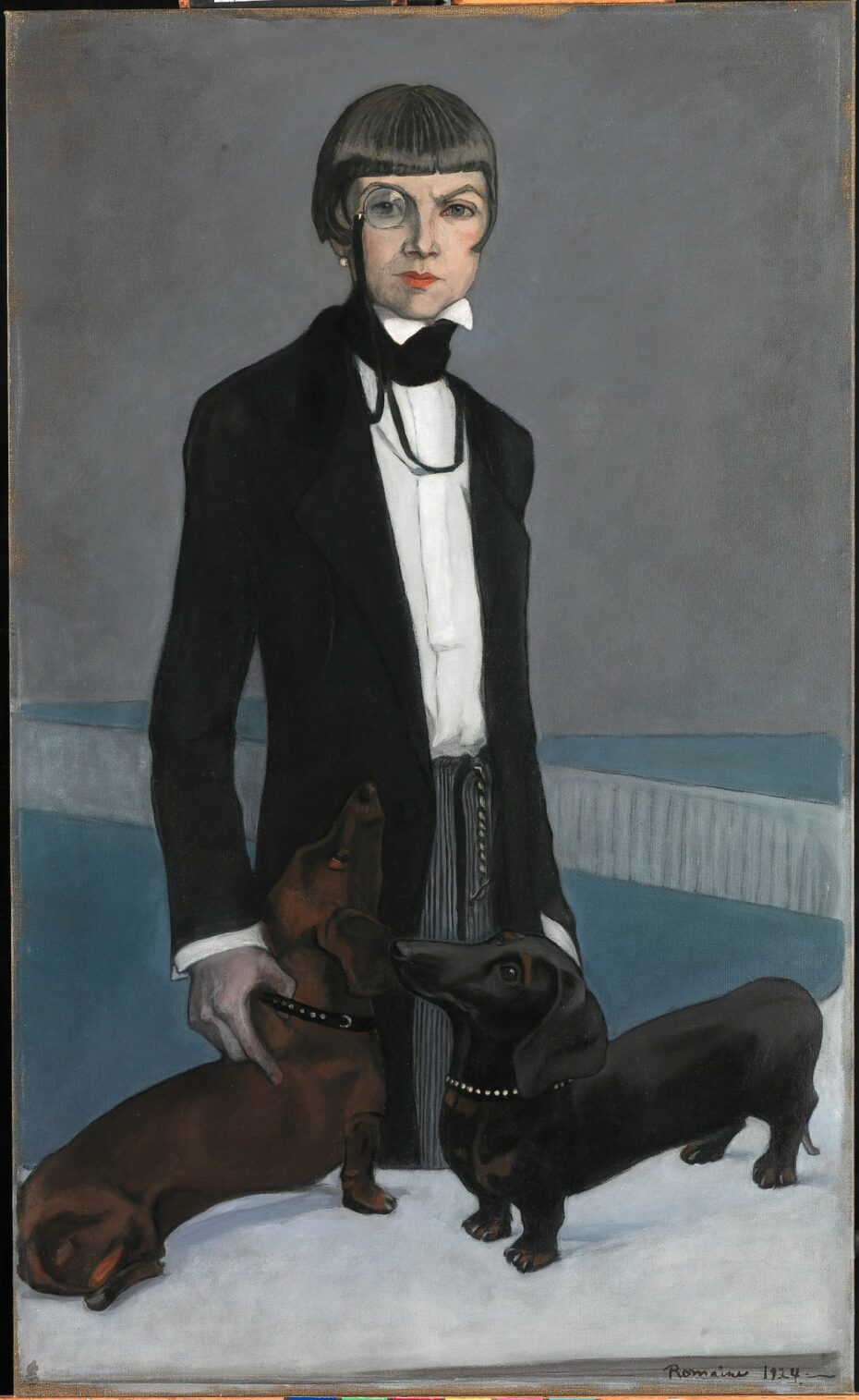

In the early 1920s, Troubridge adopted a tailored style similar to Hall’s own masculine attire. Sporting a monocle became part of Troubridge’s signature look and she was famously painted with it by Romaine Brooks (a member of Paris’ sapphic community in the 1920s). Frequently seen about town and in the press, her accessory became a discrete signal for lesbian identity; a little bit like flying the gay flag when homosexuality was socially taboo and illegal in Britain.

Androgynous style influence was beginning to make grand waves across Great Britain. It’s often forgetten that the second editor in the history of British Vogue was a woman by the name of Dorthey Todd, who happened to be a masculine presenting lesbian. Who’s to say the likes of the 20’s flapper and the practical cuts of dresses of the 1930’s wasn’t magnified by the type of people who really understood the needs, comforts and desires of ladies in the new century?

Later, Troubridge came to prefer more feminine dress that complemented Hall’s, as if attempting to promote somewhat traditional gender roles within their relationship, possibly as a result of John’s assumed trans identity, or simply to appease to the social norms and expectations of the time.

It’s said that whether or not certain historical figures were queer, they may have dressed in such a way that might allude to an identity within the community, perhaps as a form of “signaling.” Her clothing likely balanced societal expectations with personal authenticity, offering a glimpse into her world where intellectualism, artistic sensibility, and a quiet rebellion against societal norms coexisted.

Troubridge and Hall were part of a circle of lesbian and bisexual women in the early 20th century that also included the likes of Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf. While remaining queer pioneers to this day, it’s worth noting that as an upper middle class women, Lady Troubridge & co were not necessarily affected by the woes and discrimination of their sexual orientation in the same ways that other people in the LGBTQ community of their time likely were. More troubling, is the evidence Troubridge might have been a pre-war sympathiser of the Nazi party, which later persecuted queer people in addition to millions of others. Several members of the royal family and the English elite were followers of Hitler until the true horrors of his plan were revealed to the world.

The relationship between the women would last until Hall’s death, but in 1934, Hall fell in love with Russian émigré Evguenia Souline and embarked upon a long-term affair with her, which Troubridge painfully tolerated. Hall became involved in affairs with other women throughout the years. When Radclyffe Hall, passed away from cancer, Lady Troubridge took on her wardrobe, tailoring her suits to her measurements, and wearing them often.

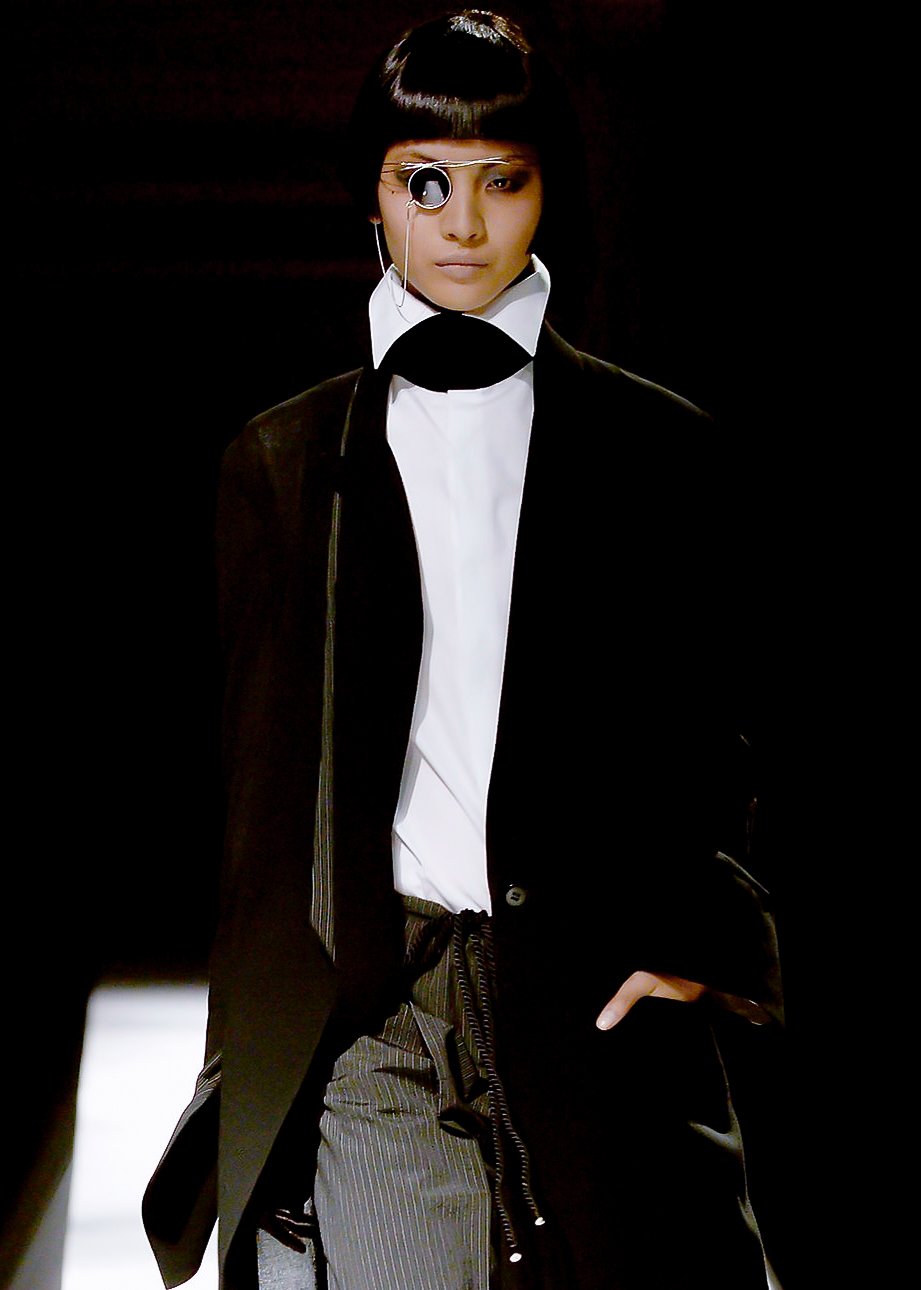

Today, the story of Lady Troubridge herself may remain shadowy, but her stylistic impact has survived. Her play on style made her a muse for the 21st century, when in 2007, the legendary Yohji Yamamoto styled a collection with at least a handful of looks styled directly to her likeness, complete with cropped bob wigs and cool black tailored ensembles. In 2019/2020 Thom Browne looked to Lady Troubridge for inspiration, giving his models exaggerated monocles, clipped in from the hair and androgynous 1920s looks.

Her attire, characterized by a certain defiance of conventional norms, mirrored the complexities of her life as a literary figure, a member of high society, and the LGBTQ+ community. The sartorial style of Lady Una Vincenzo, Lady Troubridge, was much more than a mere expression of personal taste; it was a nuanced reflection of her identity, era, and the circles in which she moved.

Words by Jessy Brewer