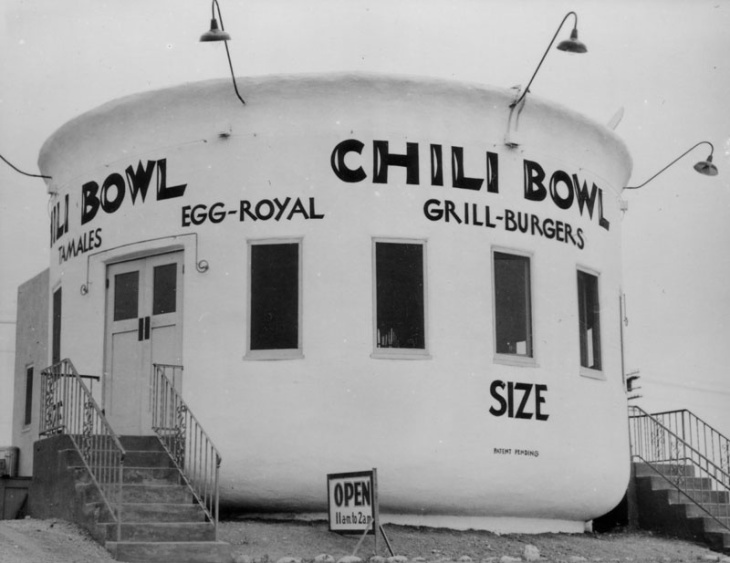

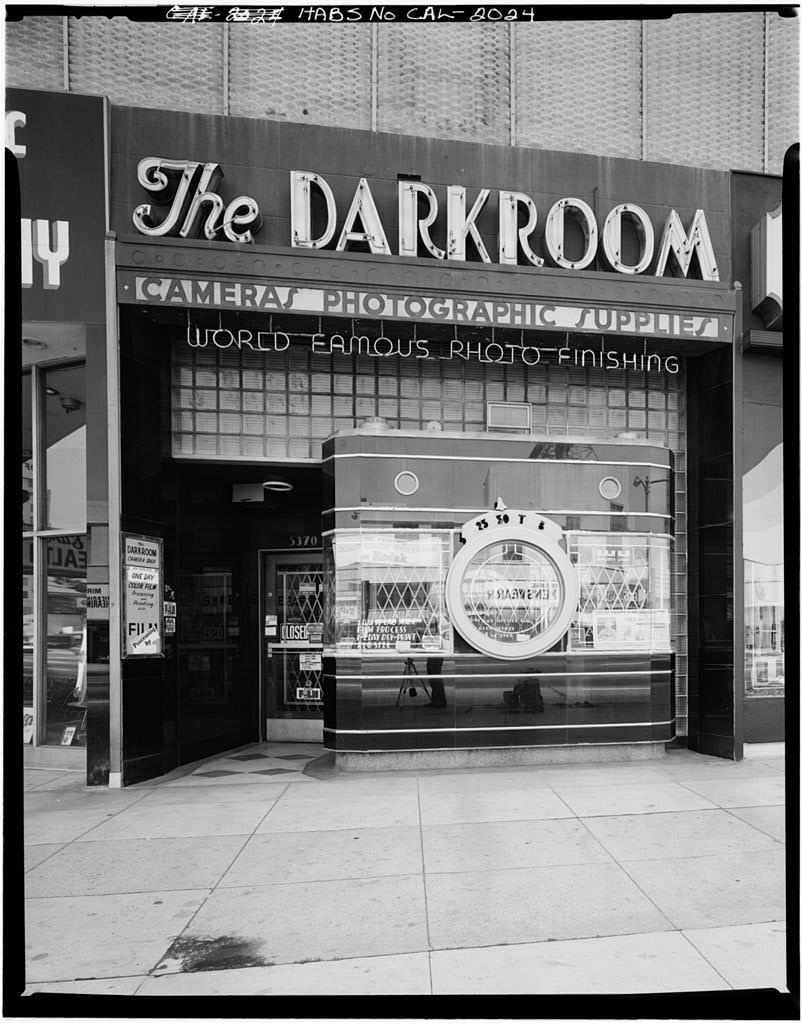

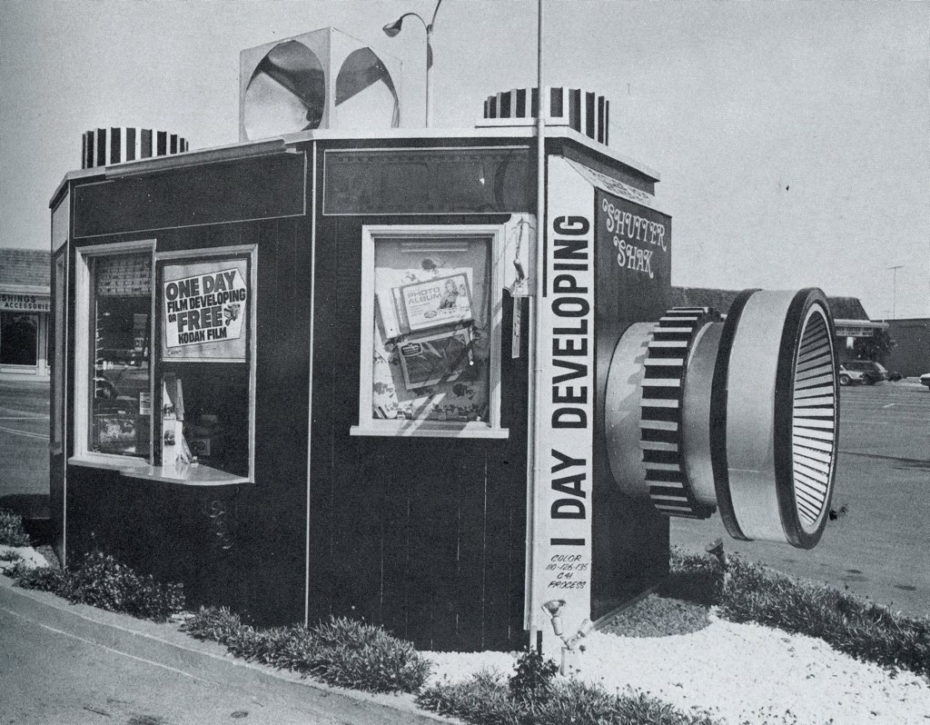

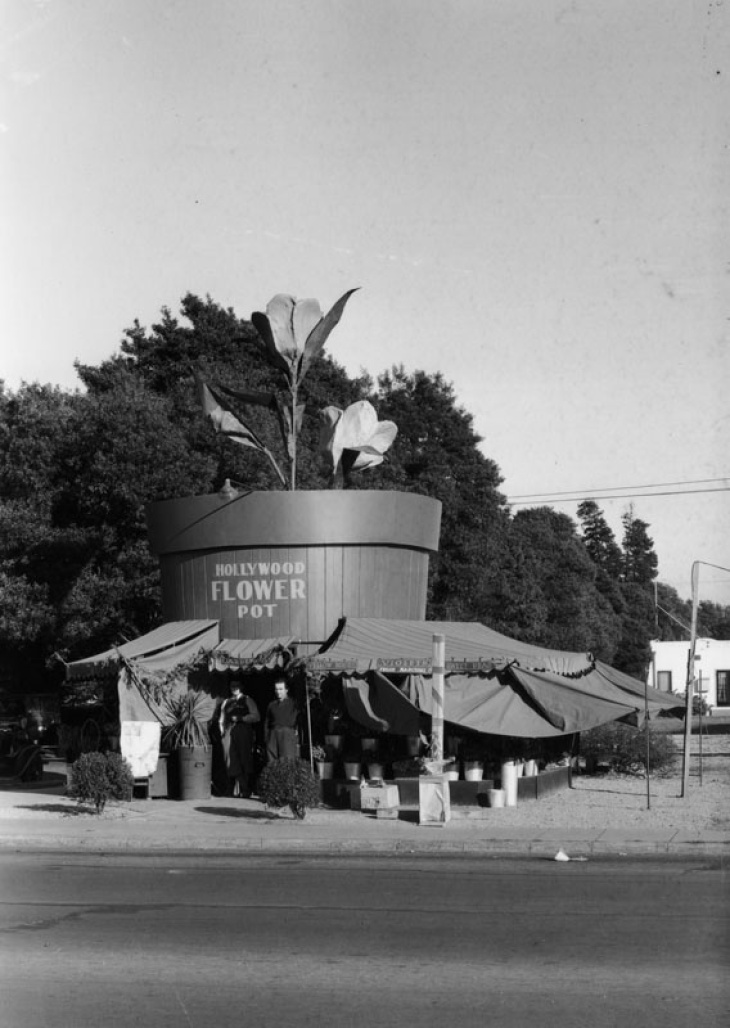

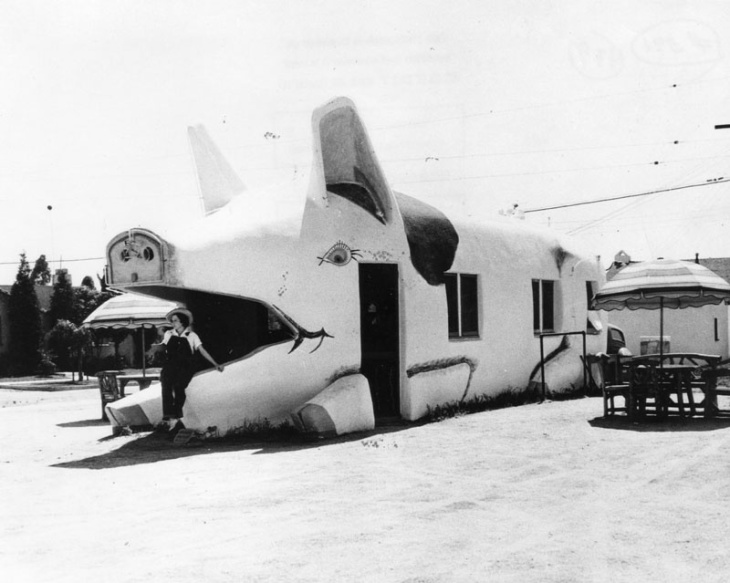

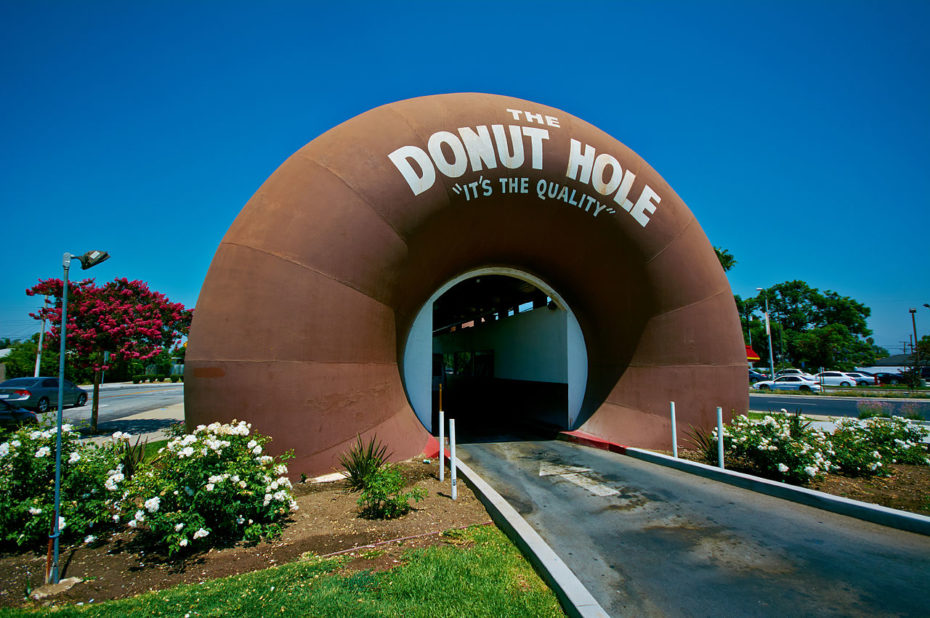

Now I know. Did you? There’s an official name for all those kitschy roadside buildings shaped like the merchandise they’re selling. Most popular in the 1920s and 30s, giant coffee pots, hot dogs, ice cream cones, beer barrels, farm animals and other eye-catching buildings sprang up along the roadside, competing for the attention of passing customers and delighting off-beat road trippers for generations to come. And it turns out – they have their own bona fide architectural genre and it’s called Duck architecture! So, if roadside kitsch happens to be one of your favourite things, you might feel as we do, that the gods have just bestowed a little gift from the fountain of knowledge upon us, and that this calls for a brief compendium of Duck buildings….

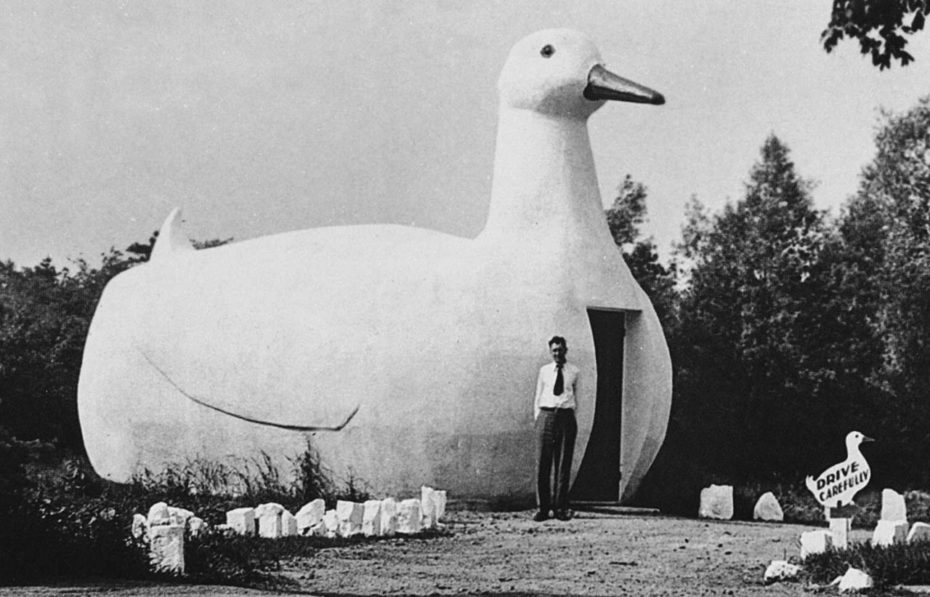

So who & why put the “duck” in Duck architecture? Well as it happens, there’s a very well-known building, shaped like a plump Pekin duck, that was built in 1931 by a Long Island duck farmer to sell his poultry. The unusual building helped garner much customer attention, but it was the subject of widespread criticism along with similar novelty architecture of the time, particularly during the rise of Modernism – a movement which didn’t take kindly to most pseudo-historical decor.

Case in point: in 1964, Modernist architect Peter Blake singled out the duck building in his book God’s Own Junkyard: The Planned Deterioration of America’s Landscape, using it as an example of the “the flood of ugliness engulfing America”. But as Modernism came to the end of its relevance in the seventies, three architects came to the Big Duck’s defence when they got together in 1972 and contended in their book, Learning from Las Vegas, that the building was actually worthy of the same respect as “high” architectural design…

The famed postmodernist architects Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour argued that next to otherwise-boring commercial structures that lined America’s roadside, the duck building was especially noteworthy for combining functional and symbolic aspects of architecture. In an effort to pay tribute to that, they coined the term, “duck”, to describe any building where the architecture yields to the symbolism and expression of its function. And thus, the genre of “duck architecture” was born…

It can be applied to all manner of novelty buildings, no matter what shape (or animal) they resemble – as long as they were originally built to symbolise their respective trades.

As for the OG Big Duck building? It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1997. Since its closure as a poultry business in 1984, it was moved to a nearby location on Route 24 briefly (try picturing the delivery truck loaded with a giant duck) before returning to its original location in Flanders where it currently serves as a gift shop selling memorabilia. Fun fact: Ford Model T tail-lights were used for the Duck’s eyes and the structure was designed by a couple of unemployed Broadway designers during the Great Depression.

Mammy’s Cupboard, founded in 1940 is another duck building with some particularly relevant history. The roadside restaurant was built in the shape of a mammy archetype, a stereotype, deeply rooted in the history of slavery in the United States. The restaurant’s founder was originally a tour guide of Natchez’s nearby antebellum mansions and thought she could attract tourists with a mammy character, which had just been famously portrayed in the 1939 Oscar-winning film Gone with the Wind. During the height of the Civil Rights movement, the skin colour of “Mammy” was repainted a lighter shade. The restaurant is still running and currently serves lunches and desserts.

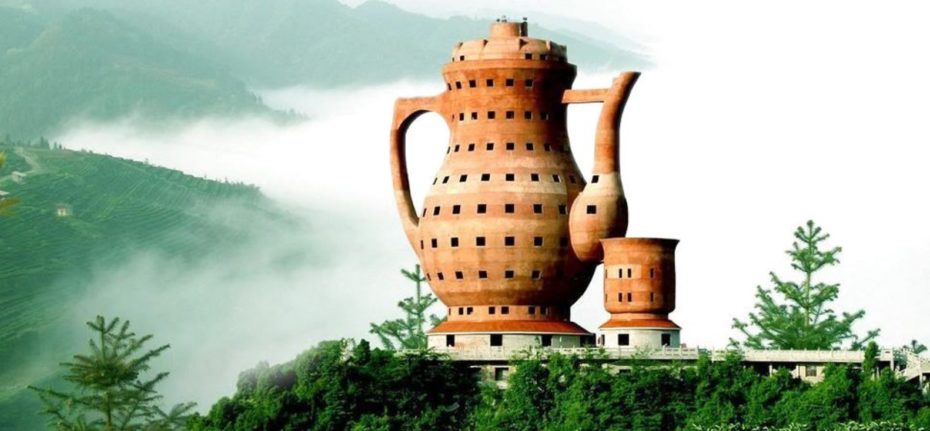

Duck architecture is certainly not limited to the American roadside, and can be spotted all around the world, from Australia to China to France…

Perhaps the most modern and close-to-home example, particularly for the MessyNessyChic team, is France’s open book-shaped national archives; the Bibliothèque François Mitterrand in Paris:

So next time you’re out and about road tripping and spot a quirky building shaped like a sandwich or a barnyard animal, you can proudly proclaim that its design is a prime and fine example of “duck architecture”…