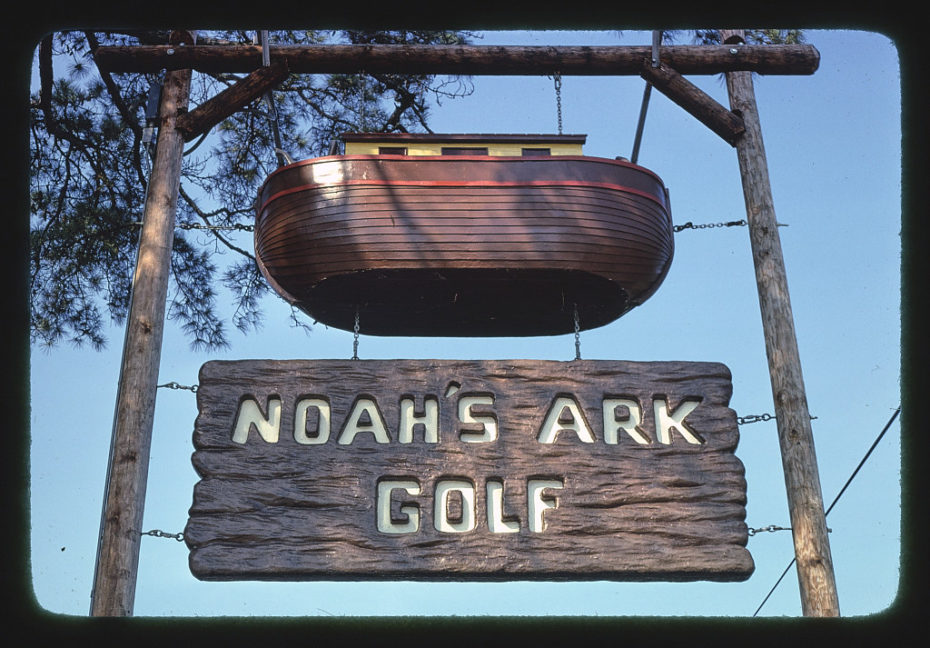

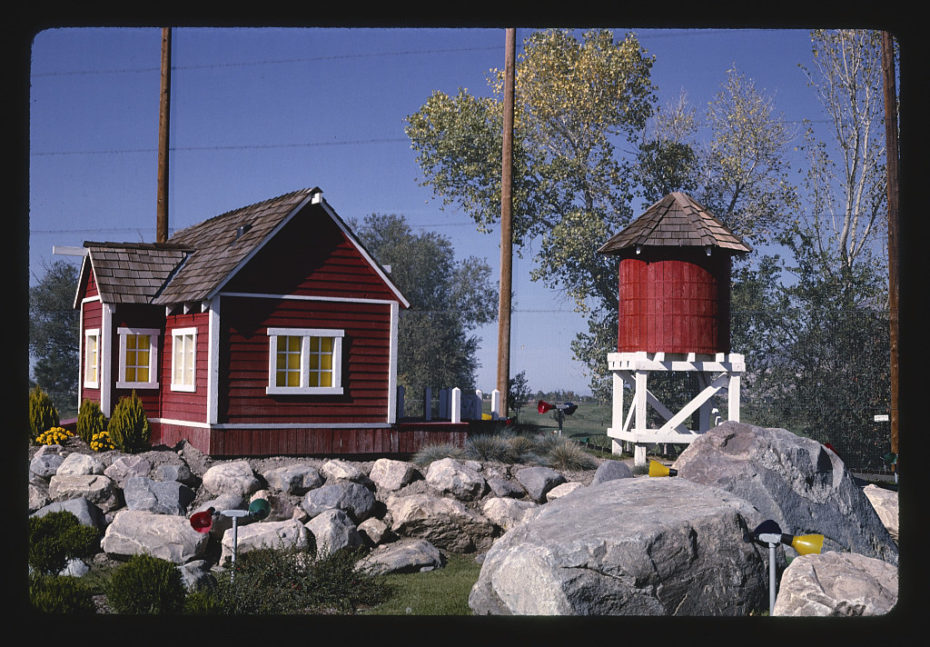

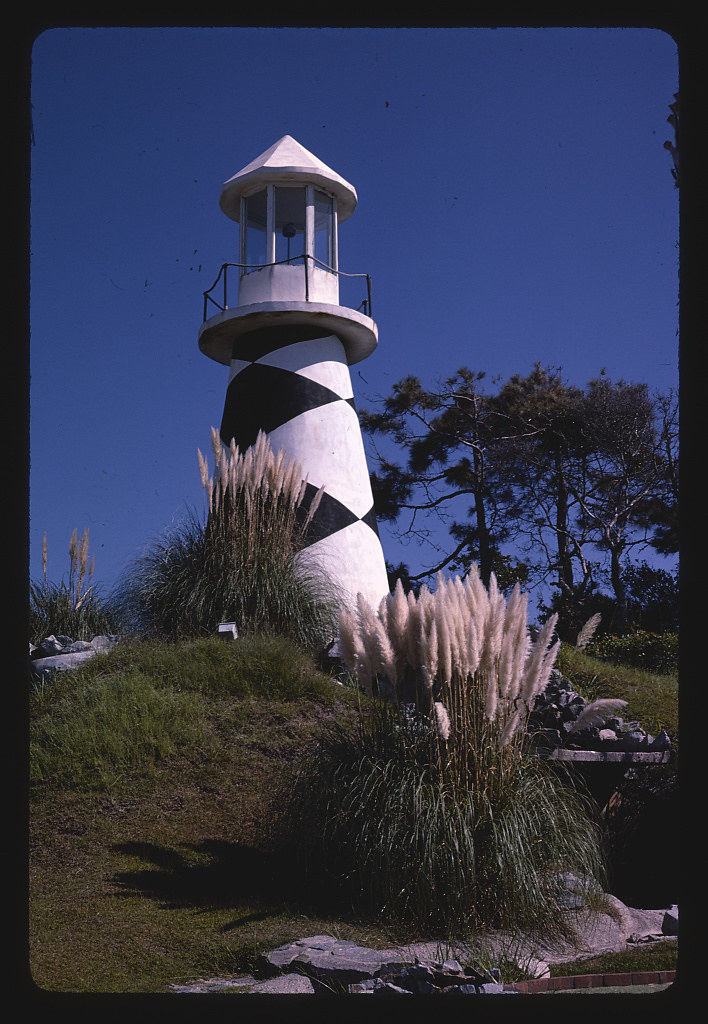

They go large in the States – even when it comes to the small stuff. And perhaps nowhere is that more true than with a particularly kitsch specimen of American vernacular architecture, the miniature golf course. A period of history defined by the automobile and the ease of travel it allowed, post-WW2 prosperity led to a boom in suburbanisation and the expansion of paved roads throughout the country. To populate these new stretches, commercial and roadside structures began cropping up; tourist architecture for the burgeoning American road trip. Often of the novelty variety – think diners in the shape of a coffee pot, giant gun-toting fibreglass cowboy – these structures were a mainstay of the American landscape for decades, until modernism rode into town. Modernism, and the expansion of the interstate system. In the early eighties, veteran documenter of roadside America John Margolies set out to capture this slice of North America that was, like all the best things in life, dying out. Of all the structures Margolies chronicled, he seemed to hold a soft spot for the miniature golf course. Tracking them across the country, from California to Texas to Florida, Margolies captured them in all their kitsch glory in his trademark Kodachrome hues.

The colossal archive (which we’ve covered before) of 11,710 colour slides that Margolies produced on his trusty Canon FT over a 40 year period is now housed at the Library of Congress following his death in 2016.

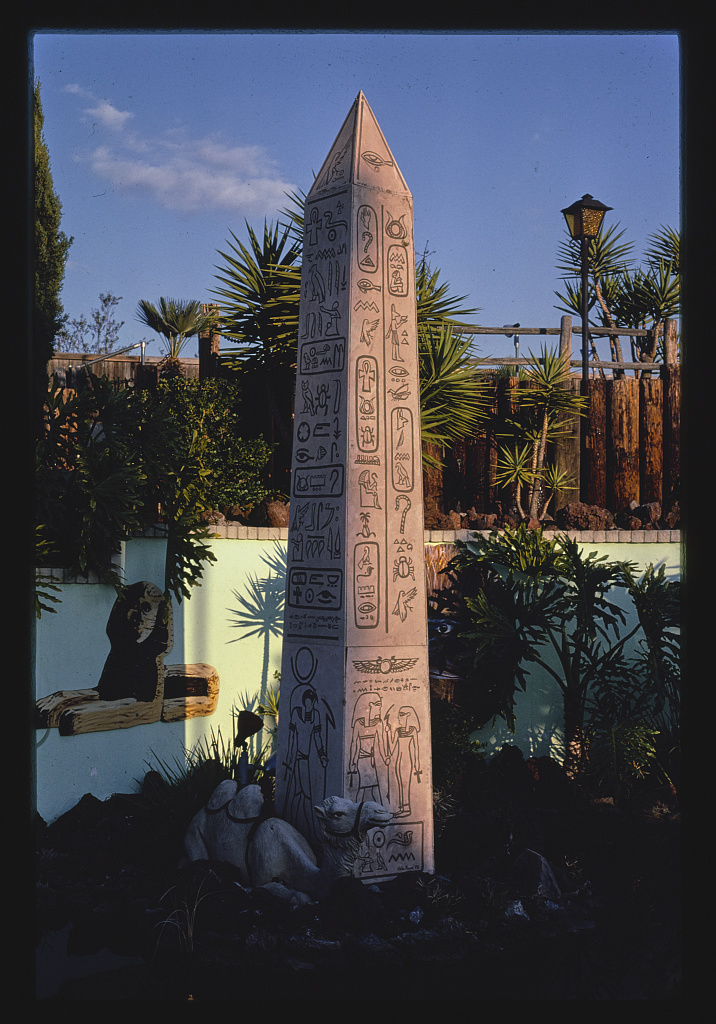

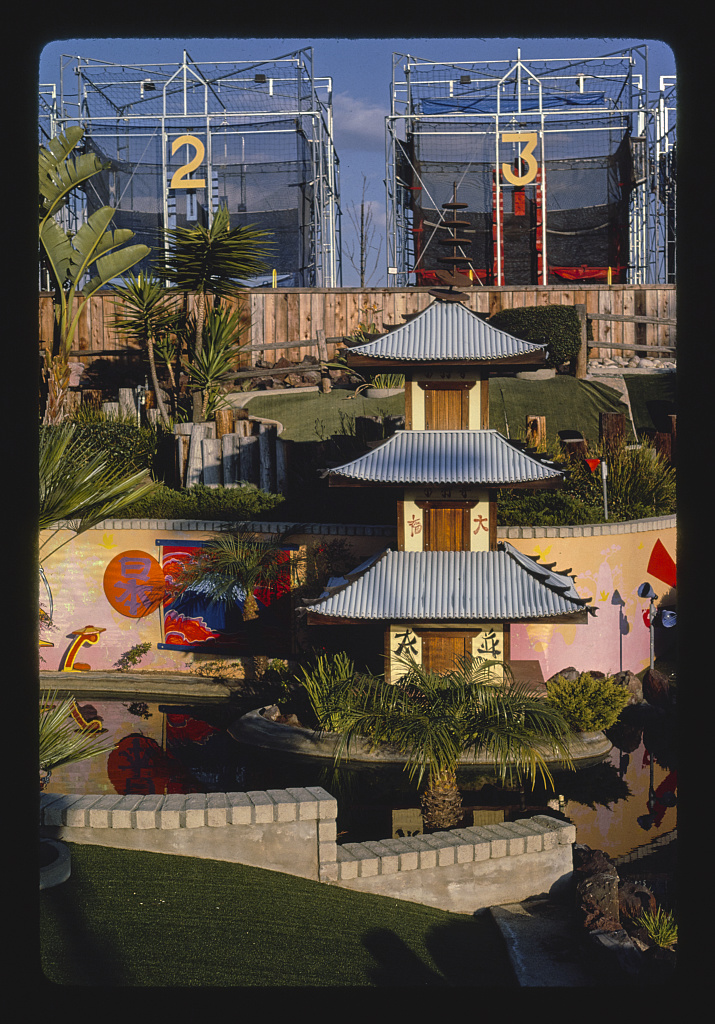

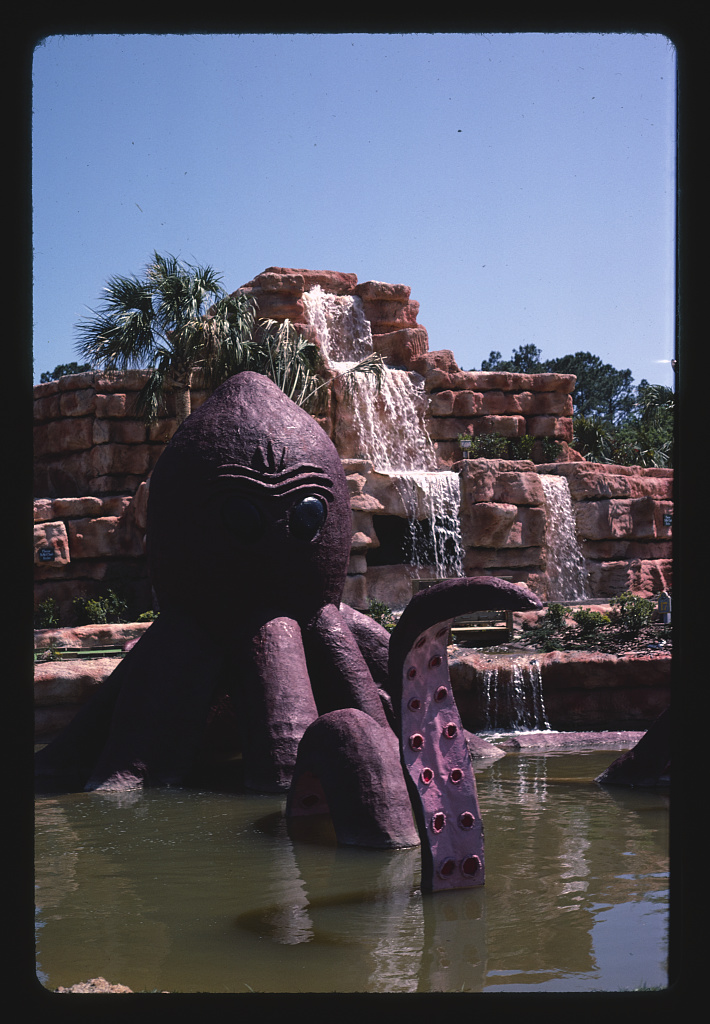

A spin through the archive will take you from a beached whale in Galveston, Texas, to a space shuttle in Fountain Valley, California, to a replica Japanese pagoda in San Diego. A pirate ship, aptly situated in Ocean City, Maryland.

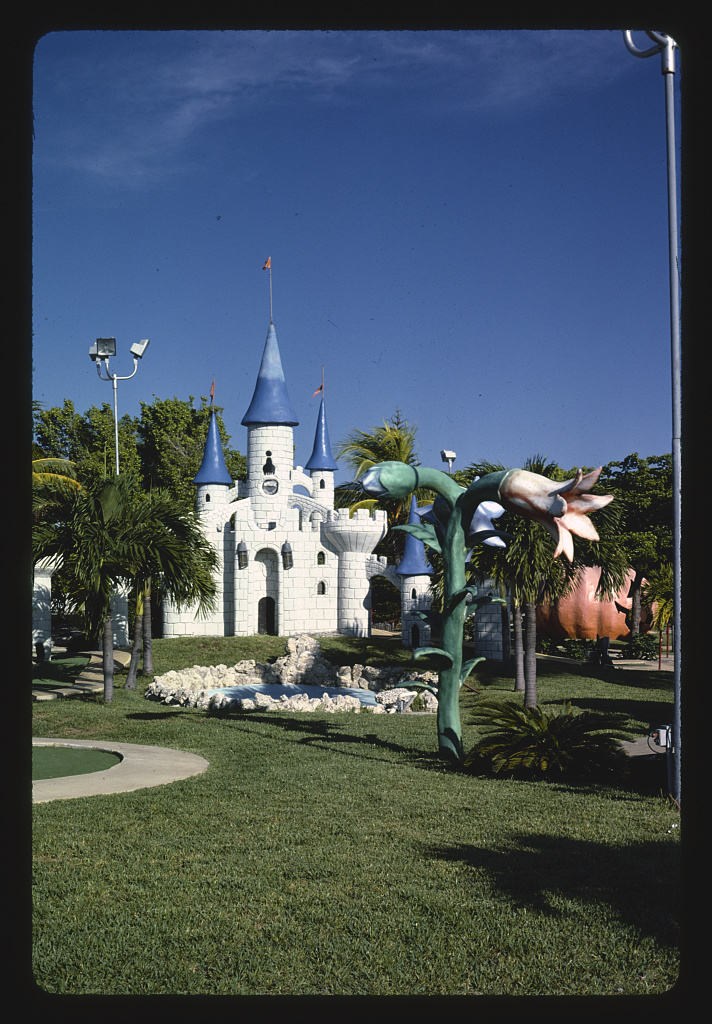

And then there are the castles.

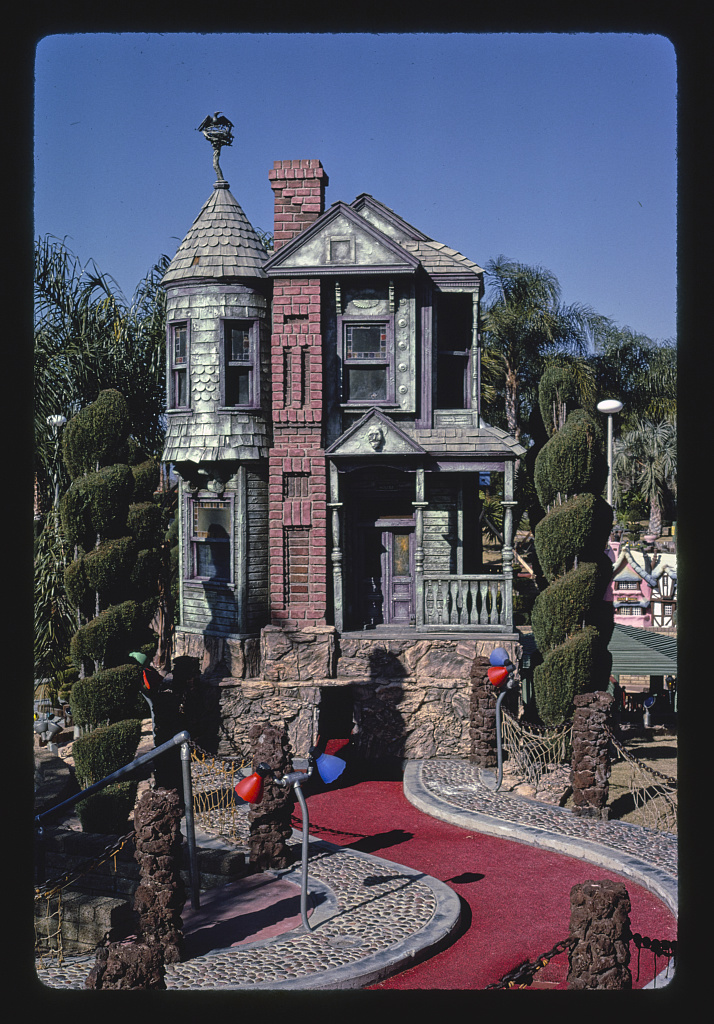

Think Disney rather than fortress. The extravagant Mystic Castle is found at Golf N’ Stuff, an amusement park in Ventura that’s been running for fifty years, whilst over in Fresno there’s a smaller but no less charming castle to be found on the Storybook course at Blackbeard’s Mini Golf. At Boomers! in Fountain Valley, now closed, could be found a distinctly toy box castle, all pink bricks and multicoloured turrets. It turns out there are three things you can be guaranteed of in life: death, taxes, and castles on miniature golf courses.

Like football, the origins of miniature golf is a hotly contested subject. Some say it can be traced back to 9th century China, whilst others claim it was the Dutch a few hundred years later. The French say it evolved out of a game called pallemail, popular in the 15th century. The Scottish, meanwhile, claim its origin as The Ladies Putting Club, established in 1827 and attached to St. Andrews golf course for the sole use of women. The full game was reserved for the big boys, obviously.

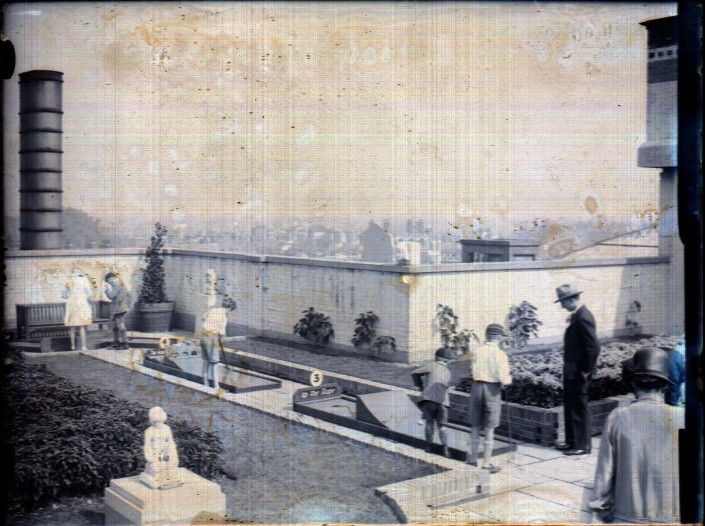

The concrete facts of the matter, though, only began to occur in the early twentieth century. The earliest documented mention of a course is in the 8th June 1912 edition of The Illustrated London News, followed by the first standardised minigolf course entering mass-production in 1916 in North Carolina. But it was in 1922 that the game was revolutionised when the artificial green – a mixture of cottonseed hulls, sand, oil, and dye – was invented, meaning it could be played anywhere, and in any weather. It could even be played on rooftops, and by the end of the 20s there were more than a hundred in New York City alone.

Minigolf struggled to find a footing on the West Coast, though, where bigwigs in Hollywood were getting concerned that it was becoming too much of a threat to cinema audience numbers – so much so that it’s said they included specific clauses in the contracts of their film stars forbidding them from being photographed playing the game. The onset of the Depression, however, put everyone’s putting plans on pause, with nearly all existing courses closed and demolished before the 30s had come to an end.

The first minigolf courses were not as we imagine them today. They were much more ramshackle affairs. The Depression led to old bits of piping and repurposed dirt being used as obstacles, and courses were often strategically placed nearby billboards or well-lit areas so people could continue playing into the night without course owners having to foot the bill. The rooftop courses themselves came about largely due to the fact that they could utilise the unused and unwanted real esate at the top of buildings. Halted construction sites were another favourite haunt of the adventurous minigolfer, who could incorporate left over building materials into unique combinations of obstacles. Even upscale restaurants got in on the action when their dining customers dried up, replacing tables with an altogether different course than they were used to serving. Minigolf was for many a means to make a little bit of money to help them get through the aftermath of the 1929 crash, adopting real estate that had lost its market value into so-called unreal estate

It was as the old guard was packing up its bags at the tail end of the 30s that a new kind of minigolf entered the scene. In 1938 Joseph and Robert Taylor – the soon-to-be kingpins of the industry – began creating and operating their own courses. Inspired by the obstacle aspect of their Depression era predecessors but without the actual Depression part, these courses had landscaping, and windmills, and wishing wells, and yes, castles. Word got around, and soon they were building them for others – even a prefabricated one for the United States Military that could be taken overseas.

Minigolf courses became extravagant affairs, more akin to amusement parks than a bit of artificial turf with some holes in it. They often followed themes, like at Storybook Land Golf in San Diego, where different parts of the world, from Egypt to Japan, were represented, albeit on a smaller scale. And these were storybook places for many at the time, the sort of places they’d only ever seen on the pages of illustrated novels. In some ways, they were a kind of precursor to places like Tianducheng in China with its replica Paris, or that city of fake French chateux in Turkey.

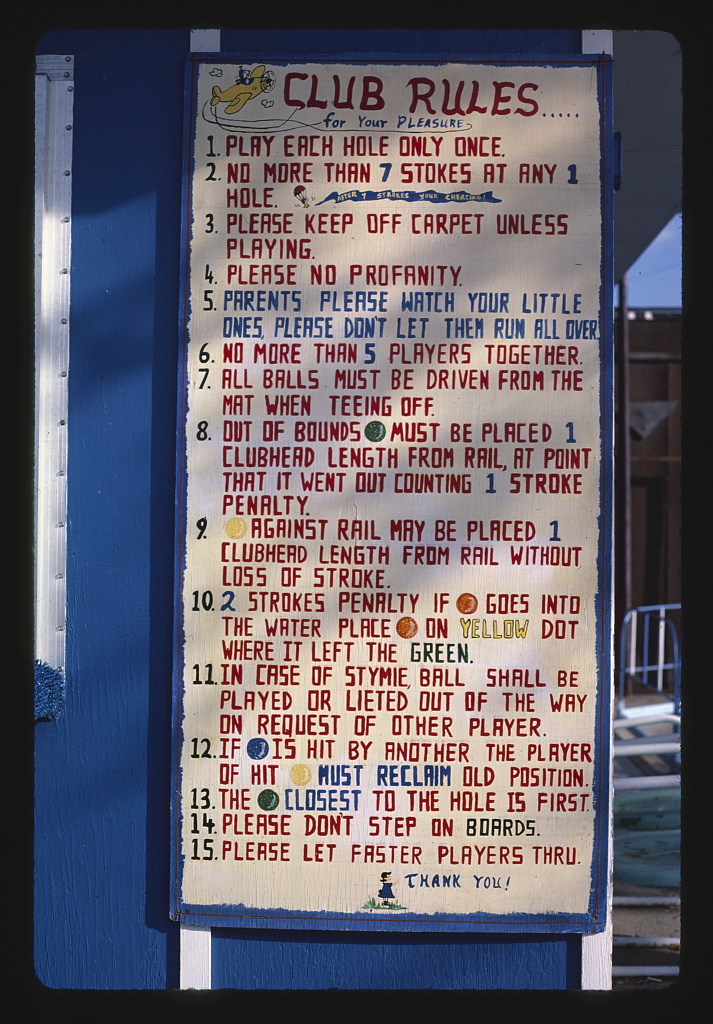

Putting away remained all the rage throughout the 60s and into the 70s, even becoming a respectable sport with its own elite players raking in large sums of prize money (we’re talking hundreds of thousands of dollars.) Miss Putt-Putt beauty pageants became a thing. But towards the end of the 70s the game was becoming less of an attraction for serious golfing adults and more of a hangout spot for local teenagers and a day out for families.

And then the interstate system came.

Under construction since the 50s, the number of travellers using local highways was dwindling and roadside miniature golf courses began to fall quite literally to the wayside.

Despite the subject matter, Margolies was a mostly unsentimental photographer. He shot straight on, or at an angle to emphasise descriptive details. His photographs lacked environmental context, to exude timelessness. With the discipline of an ethonographer, his work wasn’t for aesthetic enjoyment, though it’s often viewed in that manner today, but as a means to document and preserve an aspect of American culture that he knew wouldn’t be around for much longer. And his work bore fruit – his photographs were influential in the addition of roadside buildings to the National Register of Historic Places. He’s been compared with Eugène Atget, the French photographer who, seventy years earlier, was on a mad dash around Paris to capture it before the bulldozers of modernity came rolling in.

But Margolies wasn’t entirely unsentimental in his approach. His preferred method was to head out early in the morning, when the sky was clear and blue. “I love the light at that time of day; it’s like golden syrup,” he wrote in his book, Roadside America, “Everything is fresh and no one is there to bother you.” If the light wasn’t right, he’d skip sites altogether. And he always worked with ASA 25 film to obtain that rich saturation of colour. Margolies mantained that what he was doing had the aims of documentation in mind, but when looked at today his photographs seem to have a sense of nostalgia ingrained into them, almost as if from the moment they were taken – in some cases, the sites he photographed were torn down just days later.

By the early 80s, John Margolies was putting himself and his Canon FT between these so-called ‘exclamation points of the landscape’, according to architecture critic Paul Goldberg, and obscurity. But the interstate – and the birth of cheap air travel – didn’t quite kill them all off. Golf N’ Stuff in Ventura, California remains alive and well, as does Fresno’s Backbeard’s Minigolf. Old Pro Golf – “Have a Ball!” – is positively thriving with multiple locations in Ocean City, Maryland.

As for the less fortunate ones, like Rick and Ilsa will always have Paris, we’ll always have Margolies photographs, permanent pitstops in the onward march of time where the sky is forever blue.